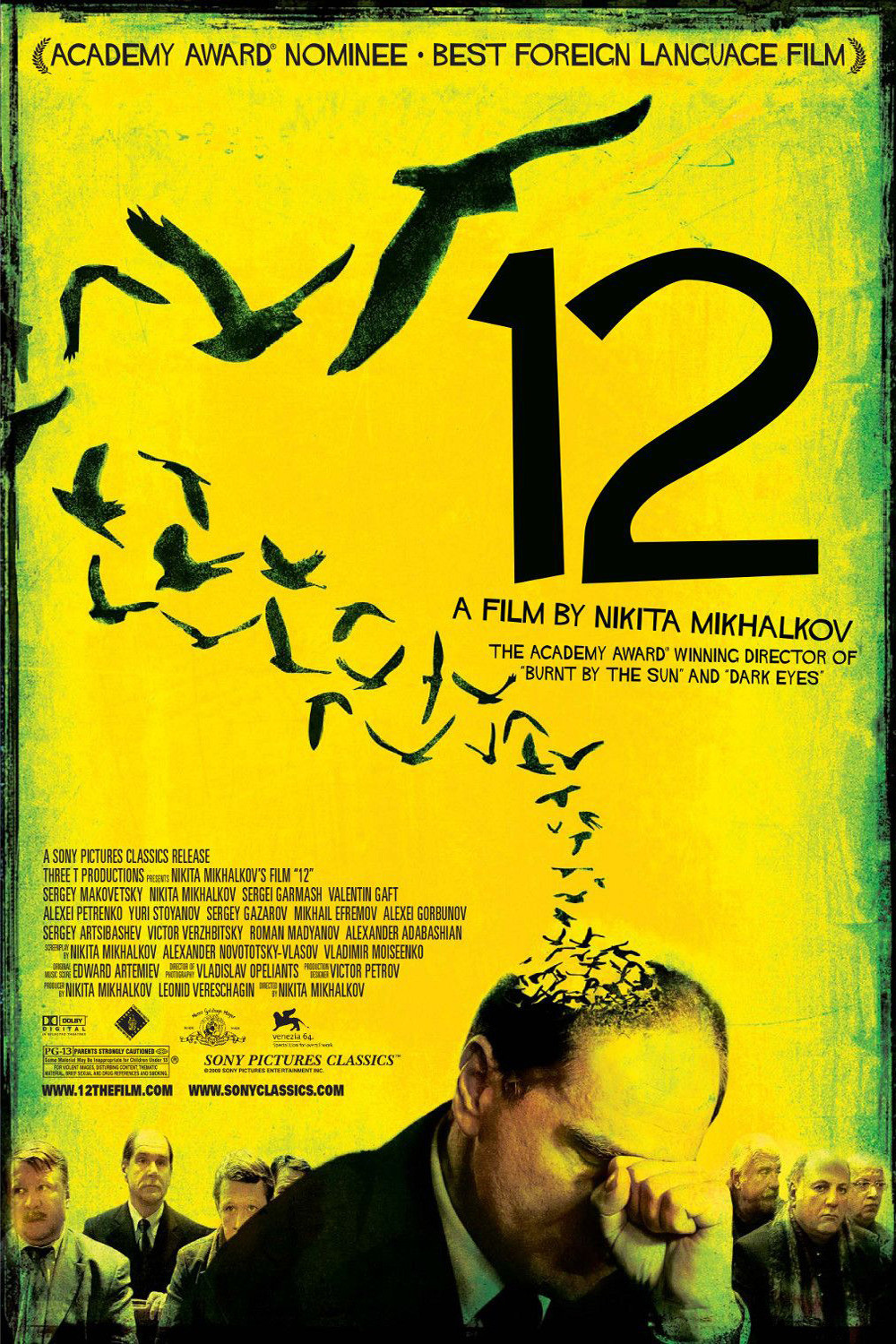

"Twelve Angry Men" remains a monument of American filmmaking, and more than 50 years after it was made, its story is still powerful enough to inspire this Russian version -- not a remake, but a new demonstration of a jury verdict arrived at only because one of the jurors was not angry so much as worried. "12" by Nikita Mikhalkov is a powerful new film inspired by a powerful older one.

You know the story. A jury is sequestered. The men are hot and tired, and impatient to go home. It is assumed that the defendant, a young man accused of murder, is guilty. A quick vote is called for. The balloting shows 11 for convicting, one against. This generates a long and dogged debate in which the very principles of justice itself are called into play.

Perhaps Russia got this film when it needed it. Reginald Rose's original screenplay was written for the CBS drama showcase "Studio One" in 1954 and presented live. Franklin Schaffner ("Patton") was the director. The telecast took place during the declining days of the hearings held by Sen. Joseph McCarthy. CBS also broadcast the Army-McCarthy hearings, and Edward R. Murrow's historic takedown of the alcoholic witch hunter. The great film by Sidney Lumet, made in 1957, now stands at No. 9 on IMDb's poll of the greatest films, ahead of "The Empire Strikes Back" and "Casablanca."

If the original story argued for the right to a fair trial in the time of McCarthy's character assassinations, the Russian version comes at a time when that nation is using the jury system after a legacy of Stalinist purges and Communist party show trials. It also dramatizes anti-Semitism and hatred for Chechens; the youth on trial is newly arrived in Moscow. The issue of overnight Russian millionaires in a land of much poverty is also on many of the jurors' minds.

None of the jurors is given a name, although director Mikhalkov gives himself the role of the jury foreman. One by one, every member of the jury tells a story or reveals a secret. Their set-pieces do the job of swaying fellow jurors to reconsider their votes but are effective on their own as essentially a series of one-man shows. There is not a weak member in the cast, and it's a tribute to the power of the actors that the 2½-hour running time doesn't seem labored. The jury is sequestered in the gymnasium of a school next to the courtroom, and they never leave it, but their stories are performed so skillfully that in our minds, we envision many settings; they're like radio plays.

Lumet famously began his film with the camera above eye level and subtly lowered it until at the end, when the characters loomed above the camera. Mikhalkov, with a large open space to work with, uses camera placement and movement instead, circling the makeshift jury table and following jurors as they wander the room. A sparrow flies in through a window, and its fluttering and chirping is a reminder that the jurors, too, feel imprisoned.

Going in, I knew what the story was about, how it would progress and how it would end. Mikhalkov keeps all of that (writer Rose shares a screen credit), but he has made a new film with its own original characters and stories, and after all, it's not how the film ends, but how it gets there.