Sometimes a person will make an enormous mistake and get a lot of time to think about it. There was a man who went over Niagara Falls sealed inside a big rubber ball. It never made it to the bottom. The ball lodged somewhere on the way down. He'd counted on his team to cut him out after he landed. Oops! Aron Ralston, the hero of "127 Hours," had an oops! moment. That's even what he calls it. He went hiking in the wilderness without telling anyone where he was going, and then in a deep, narrow crevice, got his forearm trapped between a boulder and the canyon wall. Oops.

We all heard about this. Ralston stumbled out to safety more than five days later, having cut off his own right arm to escape. He is an upbeat and resilient person and has returned to rock climbing, although now, I trust, after filing a plan, going with a companion and not leaving his Swiss Army Knife behind. The knife would have been ever so much more convenient than his multipurpose tool. I imagine that every time he considers his missing right forearm, he feels that under the circumstances he's better off without it.

What would you have done? What about me? I don't know if I could have done it. It involves a gruesome ordeal for Ralston, and for the film's audience, a few of whom have been said to faint. But from such harrowing beginnings, it's rather awesome what an entertaining film Danny Boyle has made with "127 Hours." Yes, entertaining.

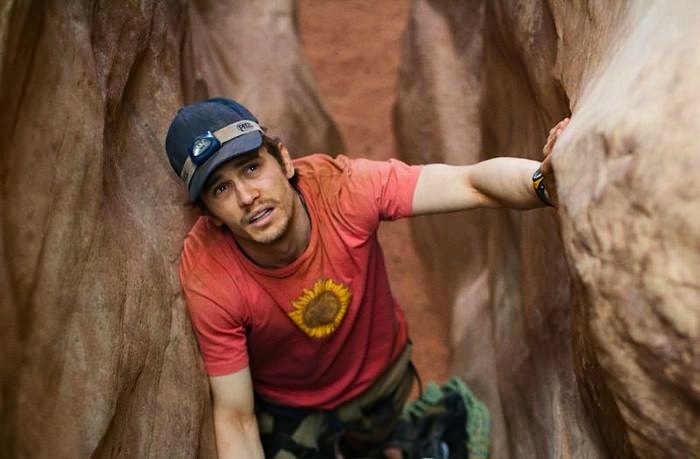

For most of the film he deals with one location and one actor, James Franco. There's a carefree prologue in which Ralston and a couple of young woman hikers have a swim in an underwater cavern. Later, during moments of hallucination, other people from his life seem to visit. But the fundamental reality is expressed in the title of the book he wrote about his experience: Between a Rock and a Hard Place.

Franco does a good job of suggesting two aspects of Ralston's character. (1) He's a cocky, bold adventurer who trusts his skills and likes taking chances, and (2) he's logical and bloody-minded enough to cut through his own skin and bone to save his life. One aspect gets him into his problem, and the other gets him out.

Is the film watchable? Yes, compulsively. Films like this don't move quickly or slowly, they seem to take place all in the same moment. They prey on our own deep fear of being trapped somewhere and understanding that there doesn't seem to be any way to escape. Edgar Allan Poe mined this vein in several different ways. Ralston is at least fortunate to be standing on a secure foothold; one can imagine the boulder falling and leaving him dangling in mid-air from the trapped arm.

Suddenly, his world has become very well-defined. There is the crevice. There is the strip of sky above, crossed by an eagle on its regular flight path. There are the things he brought with him: a video camera, some water, a little food, his inadequate little tool. It doesn't take long to make an inventory. He shouts for help, but who can hear? The two women campers have long since gone their way and won't report him missing because they won't realize that he is. For anyone to happen to find him is unthinkable. He will die or do something.

"127 Hours" is like an exercise in conquering the unfilmable. Boyle uses magnificent cinematography by Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak, establishing the vastness of the Utah wilderness, and the very specific details of Ralston's small portion of it. His editor, Jon Harris, achieves the delicate task of showing an arm being cut through without ever quite showing it. For the audience the worst moment is not a sight but a sound. Most of us have never heard that sound before, but we know exactly what it is.

Pain and bloodshed are so common in the movies. They are rarely amped up to the level of reality, because we want to be entertained, not sickened. We and the heroes feel immune. "127 Hours" removes the filters. It implicates us. By identification, we are trapped in the canyon, we are cutting into our own flesh. One element that film can suggest but not evoke is the brutality of the pain involved. I can't even imagine what it felt like. Maybe that made it easier for Ralston, because in one way or another, his decision limited the duration of his suffering.

He must be quite a man. The film deliberately doesn't make him a hero — more of a capable athlete trapped by a momentary decision. He cuts off his arm because he has to. He was lucky to succeed. One can imagine a news story of his body being discovered long afterward, with his arm only partly cut through. He did what he had to do, which doesn't make him a hero. We could do it, too. Oh, yes, we could.