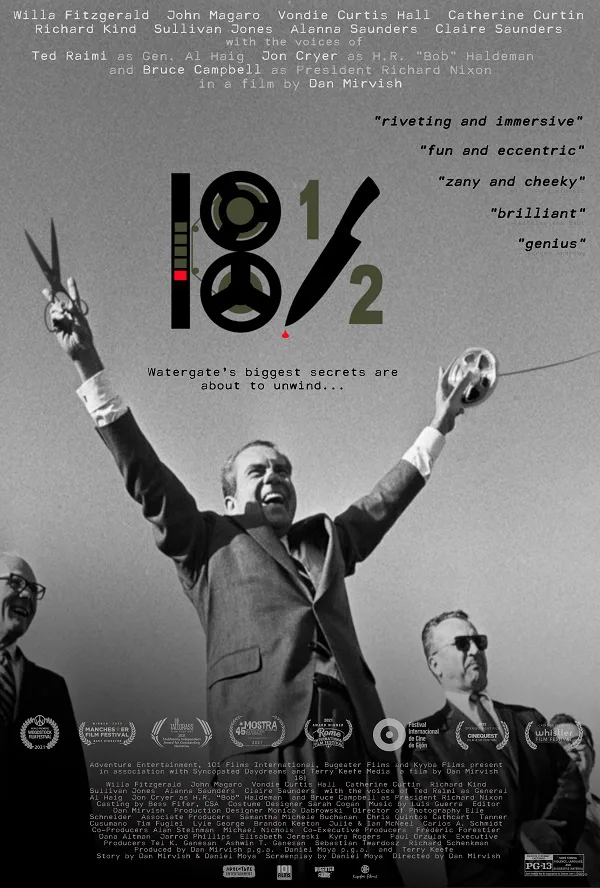

If "18 1/2" were taken to a studio and pitched to a roomful of individuals with the ability to give a film a green light, their first question would rightly be, "Who is the audience for this?" The answer, judging from the finished product, is "the people involved in making it, and whoever else happens to see it and like it." A lot of wonderful, small movies that could only be made on the outermost edges of the system fit that description. This riff on what happened to the infamous gap in Richard Nixon's White House tapes is one such movie—which, of course, is not the same thing as saying it's guaranteed to please; quite the opposite. Part of the film's specialness lies in the fact that there seems to be little rhyme or reason to the choices it makes, or when it decides to make them.

Directed by veteran independent filmmaker Dan Mirvish ("Bernard and Huey") and written by Daniel Moya, from a story by both, this is a slight and peculiar film set in the Watergate era. It clocks in at just under 90 minutes, and morphs in and out of multiple genres without committing to any of them. The film is not a romance, though it keeps threatening to head in that direction; nor is it a political satire or a conspiracy thriller, although it has trace elements of those genres as well (the closeups of recording equipment and surveillance-style shots of people being observed from a discreet distance evoke "All the President's Men," "Blow Out," and other post-Watergate thrillers). And yet it's a film that sticks in the mind after you've watched it. Every choice is made with confidence, but from an intuitive place, like decisions made by a lucid dreamer.

Willa Fitzgerald stars as Connie, a transcriptionist who stumbles across a recording of Nixon (voiced by Bruce Campbell) and aides H.L. Haldeman (Jon Cryer) and Alexander Haig (Ted Raimi) listening to the section of tape that they subsequently decide to erase. Apparently they made the mistake of holding this private listening party in a room where, unbeknownst to them, every conversation is automatically recorded—which is how Connie ended up hearing the proceedings and deciding to take them to a New York Times reporter named Paul (John Magaro).

Paul is tired of eating the Washington Post's repertorial dust on the Watergate beat. He craves his own scoop. He wants to listen to the tape himself. Connie understandably won't allow it to be taken from her possession. They agree to go to the nearby Silver Springs Motel, where they will pretend to be a married couple, book a room, and play the recording so that Paul can take notes. Connie's reel-to-reel player won't work, so they wander around the place asking if anybody else has a working reel-to-reel player (even in 1974, this is a tall order; the world had moved on to such high-tech devices as cassette and 8-Track players).

They end up pretending to be newlyweds and accepting a dinner invitation from an alarmingly forward married couple, Samuel (Vondie Curtis-Hall) and Lena (Catherine Curtin), who are staying in another room at the motel and, as luck would have it, own a reel-to-reel player upon which they've been replaying the same bossa nova album for years.

Samuel and Lena capture the film's oddball energy in microcosm. The instant they appear onscreen, they set off all sorts of alarms, but it's hard to know why, other that they're exuberant and eccentric. Curtis-Hall and Curtin, both veteran character actors, get to show sides of their talent that we've never seen. Samuel is a World War II veteran and sophisticated world traveler who wears a knotted plaid ascot and will start dancing sinuously by himself with no provocation, arms and hips swiveling. Lena is Frenchwoman who talks and talks. Her riffs are so nonsensical that they verge on beat poetry.

They met in occupied France. "What did you do during the war?" Connie asks Samuel over dinner. "We won," he replies. The sentence lands with sinister weight because even though it's not a real answer, Samuel says it matter-of-factly but with a hint of a dare. When Lena lets Connie and Paul into their suite, she doesn't just open the door, she throws it open in an odd way that's as seemingly unmotivated as everything else she does. (When she launches into a long riff during dinner, the movie jump-cuts between different takes of the actress performing the scene. There's one brief shot where Curtin is speaking into a baguette as if it's a microphone.)

Another ace supporting player, Richard Kind, has a subtler yet somehow equally unsettling role as the motel owner, who 's a fountain of too-much-information. Delivering a message to Connie and Paul's front door, he apologizes for his handwriting: "I have a slight tremble in my hand. I've had it since I was a kid. It's mercury poisoning. I used to suck on the thermometer."

What's his deal? What's Samuel and Lena's deal? What about Connie and Paul? Do they have a deal? Why do all of these characters seem so untrustworthy? They're just a bunch of eccentrics, right? Is the film a joke of some kind? Sometimes it seems to be—especially when we're listening the tape of the Watergate tape, and the conspirators are yammering nonsense lines like, "Damn Howard Hughes. Damn him and his sandwiches!" But then it'll turn sinister and upsetting, while still not entirely committing to making a serious or deep statement on anything, and expect us to reconcile what it was and what it turned into—and that's the point where it'll go back to being silly again.

Mirvish, who cofounded the Slamdance Film Festival, was mentored by the influential director Robert Altman. This feature is his best-directed work and also his most Altman-like, with its creamy lighting and overlapping dialogue and long takes and fluid, sometimes arbitrary-seeming zooming towards and away from actors. Mirvish's production partner, longtime cinematographer and cameraman Dana Altman, is Robert Altman's grandson. He had his first credit as a camera assistant on "Nashville" at age 15. Some of the compositions evoke that film as well as Altman's "Brewster McCloud" and "The Long Goodbye."

But for the most part, the movie has the feeling of one of those small indie films—usually but not always based on a play—that Altman did in the 1980s, after he'd had a string of flops and couldn't get studio funding anymore and decided to have fun messing with his signature style, in features such as "Streamers" and "Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean," and "Secret Honor" (about Richard Nixon on the eve of resignation) and the HBO series "Tanner '88."

All this backstory and comparison is of interest to a narrow slice of the movie-watching population, admittedly—but in fairness, so is the film, a private art-house joke that does its own thing. What is it up to, besides doing what it pleases? Hard to say. But those who declare it pointless should be prepared to eat their words at some future date, as some detractors of Altman's supposedly minor 1980s films did once they took the trouble to think about what the thing was, instead of fixating on what it wasn't.

"Everybody is looking at A when B is really happening," a character in the film says, "and no one is paying attention."