In the 25th year of their career together, a famous string quartet receives some devastating news. Peter, their cellist, has been diagnosed in the early stages of Parkinson's disease. This bombshell interrupts the steady pace of their work and exposes personal issues that have long remained latent.

"A Late Quartet" does one of the most interesting things any film can do. It shows how skilled professionals work. I knew about string quartets in general. Now I know more about them in practice, especially about how they require four talented individuals to form into one disciplined voice. I suspect any serious music lover will be convinced that Yaron Zilberman's film knows what it is talking about.

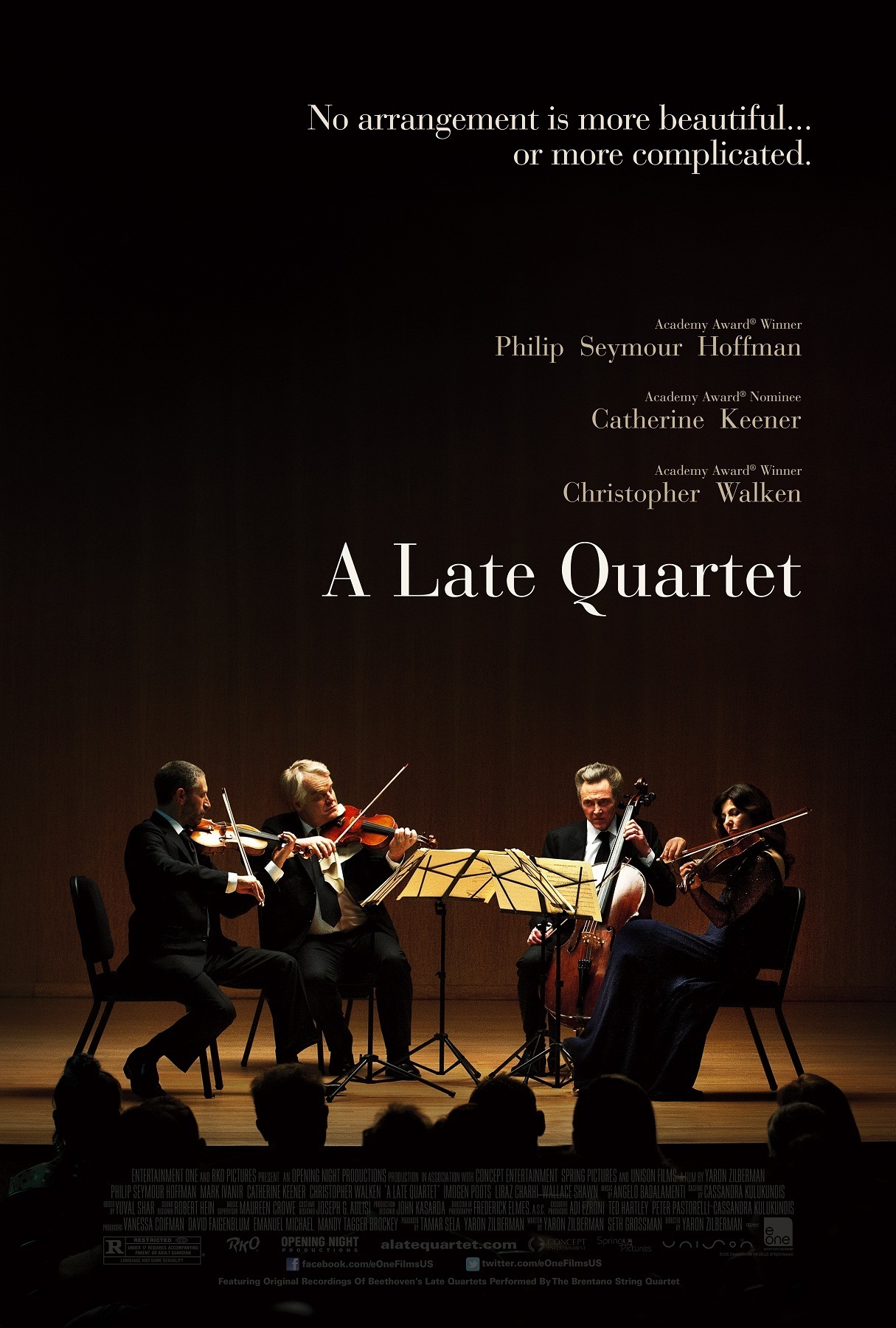

One of the pleasures here is to see familiar and gifted actors forming an ensemble of their own. Philip Seymour Hoffman, Christopher Walken and Catherine Keener join with a newer face, Mark Ivanir, to play the members of the Fugue String Quartet, a world-famous ensemble based in Manhattan. Walken is Peter Mitchell, the cellist, who is the wisest and most thoughtful member of the group. Hoffman and Keener are Robert and Juliette Gelbart, the second violin and viola, who are married. The first violin and youngest member of the group is Daniel Lerner (Ivanir).

Peter notices a weakness in the fingers of his left hand, consults a specialist (Madhur Jaffrey) and is startled to learn that even before a blood test and a brain scan she can tell him, on the basis of a few simple physical tests, that she suspects Parkinson's. He reveals this quietly to his fellow musicians. In this moment and throughout the film, Christopher Walken reminds us that although he often plays caricatures and joins in kidding his mannerisms (see the recent "Seven Psychopaths"), he can be a deep and subtle actor, particularly good at suggesting deep intelligence.

His character's announcement inspires a bright idea by the second violinist, Robert, that he and the lead violinist, Daniel, could begin to switch chairs. Since the loss of their cellist doesn't require a rearrangement of the violins, it's clear that this idea has been long smoldering in his mind. It is quickly shot down and precipitates other buried issues, including a situation of adultery, and another unsettling revelation that Daniel has been having an affair with young Alexandra (Imogene Poots) — who is the daughter of Robert and Juliette.

These melodramatic themes are intercut with knowledgeable scenes showing the Fugue Quartet in rehearsal and performance; they're preparing to present Beethoven's String Quartet No. 14, Op. 131, itself a late work by the master with a certain funereal air. Peter believes it could provide his farewell performance, and so it does in an unanticipated way, allowing Walken to display the great depth and dignity of his character.

How much does one need to know about classical music to appreciate this film? Not very much. Like all masterful films, it contains what is needed to appreciate it. All that is needed is an interest in human nature, which during the quartet's period of crisis is abundantly revealed. Actors such as Keener, Walken, Hoffman and Ivanir are frequently seen in roles that don't really test them. That's the nature of the commercial cinema. What a pleasure to see them sounding their depths.