Nancy Buirski has a lot on her plate these days. The documentary filmmaker is working on a new project, "The Rape of Recy Taylor," about the rape of an African-American wife and mother by seven white men in 1940s Alabama. She's also at Cannes for the premiere of "Loving," the latest film from director Jeff Nichols ("Midnight Special," "Mud") which not only she produced but was inspired by her 2011 documentary "The Loving Story," about an interracial couple who were thrown in jail and exiled from their home state in Virginia.

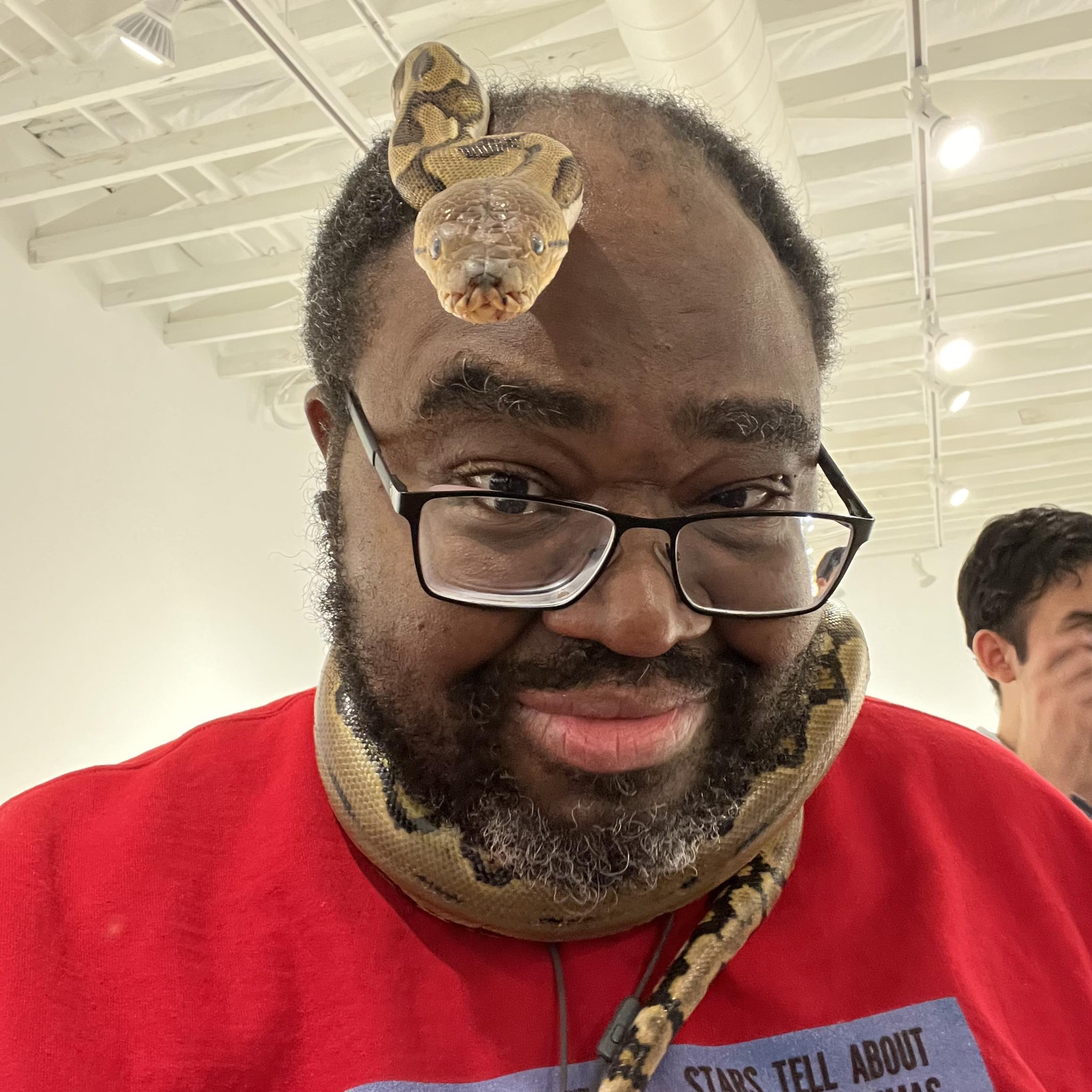

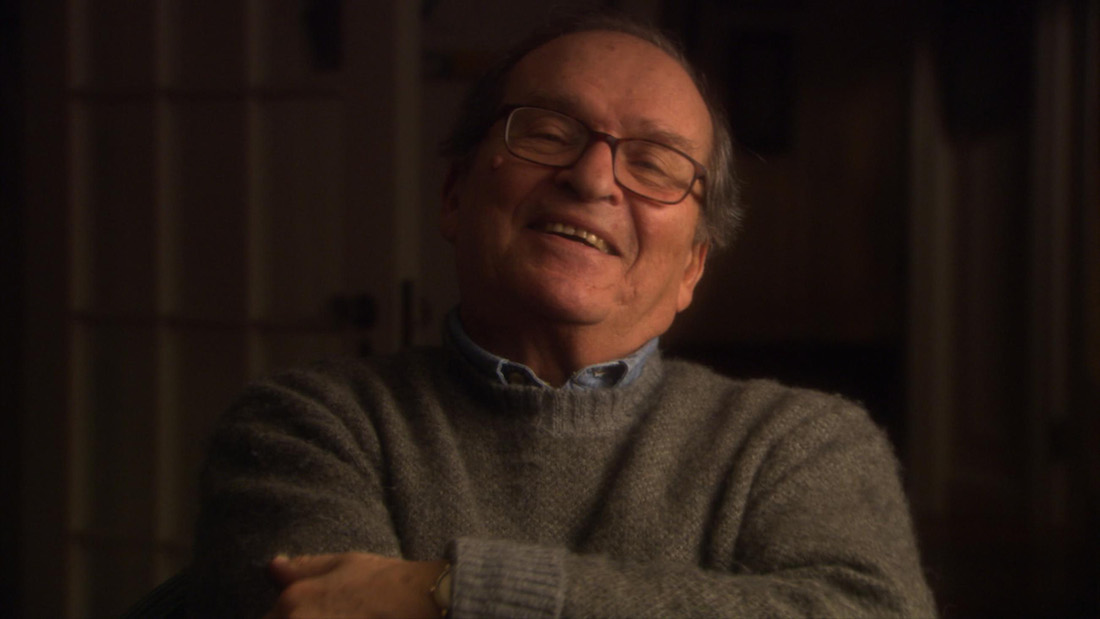

But even with all that going on, she's been showing off another film she's completed, "By Sidney Lumet" (which played at Cannes last year). Recently, she's gone to fests like Tribeca Film Festival and the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival (which she founded). "By Sidney Lumet" features the late, veteran filmmaker talking about his life and times, as interspersed with clips from his long list of movies as well as the TV productions and films he starred in as a child.

This project was practically dropped on Buirski's lap. The interview was actually filmed by filmmaker Danny Anker, who passed away in 2014 from lymphoma complications. When Buirski came to PBS doc series "American Masters" to pitch ideas a few years ago, she was asked if she would like to make a doc out of Anker's 14-hour sitdown with Lumet. After viewing all of Lumet's 44 feature films and picking out many memorable moments from his convo (the movie starts with him recalling witnessing a debaucherous gangrape in Calcutta in his younger days), she had enough to make a fascinating chronicle of a filmmaker who considered himself more a workaholic than an auteur.

Buirski took some time out from her many projects to talk about "By Sidney Lumet" and everything she learned about Lumet while shaping it.

What made you decide to take on this project?

Well, it's interesting. It was offered to me and I had to decide. Obviously, I didn't automatically agree, but there were two main things. One is that I'm a big fan of Sidney Lumet. I don't like every movie he's ever made, but I think that he's an amazing filmmaker who has gone somewhat underappreciated in recent years, and I wanted to draw more attention to his work. And the interview itself, which was extremely long—it was over fourteen hours—offered me material that gave me a chance to tell, I thought, to approach a film about a filmmaker in an unusual way. And I wanted to do something fresh. I didn't want to just do another biopic. I wanted the idea that I could have Sidney Lumet tell his story and let him guide us through his life and his work and his world—[it was] so unusual and a great opportunity to do something a little different. And the interview was just excellent. So, even though I had a lot of work to carve out of that interview, to find the main threads that I felt would be most interesting, there was a lot to work with there.

The film is disjointed, but in a compelling, entertaining way, with Lumet in this elder-statesman role, telling fragments of his life while scenes from his work highlight or accentuate those remembrances. Is that what you were looking to accomplish with this film?

I was looking for a throughline. I didn't want it to be one anecdote after another. I felt like there was—when I heard the story about the rape on the train, that opened up to me a large possibility. I felt like it could be, consciously or unconsciously, an inspiration for many of the more moral films that he made, you know. He makes a point that he never did those intentionally. He didn't direct what he called "the moral message." The films that have the most staying power for us—for me, anyway—the ones that still feel relevant today are the ones that have that as a foundation. To me, films that last are usually films that are personal in some way. And, so, I found there was this relationship between this horrible incident that he witnessed—and, ultimately, we found out that he never acted on—and his concern with corruption and people standing up to corruption, people standing up against the mob. Heroic people, noble people, who stand up. And even though he doesn't make that connection in the interview, and has rarely talked about that incident on the train—I think that may be in that only interview that we had—I thought that this was an interesting hypothesis, an interesting way of approaching this. And most people that know him and who have seen the film don't think that at all. I think that they feel it was a very reasonable approach to his work and a reasonable hypothesis to make about his work.

How did Lumet sitting down for all this even happen?

Well, first of all, it did start with "American Masters." Susan Lacy, who was then head of "American Masters," wanted to do an interview with Sidney Lumet. And she approached the people to do it, like Danny Anker. I don't know whether she hired them, but she paid for the interview. And so they went ahead and they did it over a three- or four-day period, and that was it. Now, it was interesting that you mentioned that it was an elder-statesman kind of thing. I think you're right, but he didn't know he was not making more films. I mean, the last film he made, "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead," at that point was the latest film he made. It wasn't necessarily going to be the last film he made. And, then, a couple of years later, he ends up dying from cancer. But that's an extraordinary movie to end your career on.

"Before the Devil Knows You're Dead" was more of a dark, unpleasant film to end a career on. In fact, those later movies, like "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead" and "Critical Care," were more cynical than the films he did in the ‘70s and ‘80s. At least those films had people you could root for.

I think you're making a really good point, because he does find these heroes in the ‘70s. And he says, at one point in the interview, "I love rebels." And, so, he focuses on rebels. And they are what he needs them to be. And I think he might have liked to have been a bit more heroic himself or a little bit more rebellious himself. But I think he rebels in many of the movies he makes. But, towards the end of his life, I completely agree with you about "Critical Care"—it's a very weird movie. And there's very little redeeming of value in "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead." It's just a very realistic, a very deep and dark view of a family relationship. And, so, the closest person that you can imagine in that movie as noble would be the father, who somehow gets back at the son, as unpleasant as that is. He does, you know, exercise some vengeance. But it's still a brilliant movie. I mean, what I found interesting about it is that, technically, it's so smart and the acting is so fine and it's so well-constructed and I think much better than many of the other movies towards the end of his life.

In the film, he talks about being more being a working filmmaker than an artist.

That's right, and he didn't want to be. I mean, he didn't believe in auteurism. He felt he didn't have to. He didn't have an agenda. He didn't feel he had to repeat his style, from film to film. In fact, he makes the point in our movie that style is a function of what the movie is about. And once you determine what the movie is about—emotionally about, not intellectually or plotwise, but what it's about emotionally—then the style follows that. Every decision you make, every creative decision, is in the service of what that film is about. And, so, that can vary dramatically, right? And, so, I think that what's consistent is what he says at the end of our movie: "Is it fair?" And I think that fairness does come out in a lot of his movies—even the lighter movies, the silly movies. Even fairness plays some role in that too.

What did you learn the most about Lumet while making this movie?

I learned a tremendous amount from him. I mean, one of the things about Sidney Lumet is that he's so generous. He gives so much of his technique to you, and he doesn't hold back. He's not egotistical—at least it seems that way. So, he volunteers a lot of information that might be harder to pull out from somebody else, you know. It's like a magician revealing his tricks. And, as a filmmaker, I found that very gratifying, because I just ate it up, you know. I loved listening to that stuff. I also wanted very much not to make this film ... personally, I didn't want it to feel like a lecture. I wanted it to feel, as the clips were presented, that they happened almost inevitably. They are organic to the film. They're organic to what he's saying. They kind of prove his points. People asked me [during the making of the film], "Are you gonna bring on other people to echo what he says?" And I felt like I didn't need to do that because I felt the films did that. And the way the films are worked into his story—it's not that concrete. It's not necessarily linear. We move back and forth. And guess what? The audience goes with that. They came to be fine with it not being the obvious, linear approach to his work. So, that told me something about the way audiences respond to this kind of material. That they really can go with you if you lead them in a certain way, and if it has some kind of organic logic. You don't have to be so explicit. That was my hope—that I could get away with that.

So, I guess I'll come out and ask: what's your top five?

Oh, I can't. [Laughs]

I didn't want to be an asshole and ask if you had one favorite Lumet film.

It's OK. What I will say to you is that I am dumbstruck by the fact that his first film was "12 Angry Men" and his last film was "Before the Devil Knows You're Dead." I think that those are two incredibly important movies. They're classics, and I think anybody who bookends a career with two such important films—it strikes me that I'm in awe of that. And, then, there are so many that I love and, as they come up on the screen while I'm watching them in the film, I just kind of smile when I see some of these films because I think they're so good. "Dog Day Afternoon"—probably very high up on the list. "Network"—certainly very high up on the list. But I have a real affection for films that didn't necessarily do that well when they came out, like "The Sea Gull." I think "The Sea Gull" is a beautiful movie, and that really didn't do very well when it came out. I think "Long Day's Journey Into Night" is a very important film, and there's a new [version of the] play that just opened on Broadway and is getting all sorts of wonderful reviews. But I can't help but think that this film is just as good as that play is. So, let's put it this way: I have affection for certain films. Maybe it's because of a particular performance or because of the way I know how he feels about it and that's impacted me. So, that's the best I can answer that question. [Laughs]

All right, what do you want people to know the most about Sidney Lumet after viewing "By Sidney Lumet"?

Well, first of all, I want them to be reminded that he did make some of these amazing films. A lot of people have seen ... they know of "Serpico." They know "Network." They know "Dog Day Afternoon," but they don't necessarily connect it all, these amazing films, with the same filmmaker. So, I think even though he was not as you and I might consider an auteur, he is a man who made some extraordinary films. And very few have that many films that we can call classics, and I think he has. So, I want very much to remind people of that. And, then, I'm hoping that they will be inspired by the process, what made it personal for him—what was important about his life and how that life found its home in these movies.