I must've blocked the real-life details of writer James Frey's professional scandal out of my mind, because it wasn't until a half-hour into the movie version of his drug rehab book "A Million Little Pieces" that I started to question why, if this story was true, it felt fake.

To be more precise, the movie's story felt too familiar in the way that timeworn showbiz cliches feel too familiar. Frey's source book was originally published by Random House as a memoir in 2003 and championed by Oprah Winfrey on her televised book club. It became an object of scandal in 2006 after The Smoking Gun website revealed that a lot of the dramatic and/or salacious details recounted in Frey's supposedly true story couldn't be corroborated, including a tragedy that had Rosebud-like significance to the main character. It wasn't even possible to locate a police mug shot of Frey, despite claims in the book that he'd been arrested for a variety of crimes, some of them outrageous. The publisher ended up recanting their description of Frey's book as a true story, and offered refunds to readers who felt deceived.

This film adaptation treats Frey's book simply as a story, not questioning or even acknowledging challenges to its truthfulness, but rendering it with poker-faced reverence. This is a fine approach, actually. As innumerable classic films from "Young Mr. Lincoln" and "Dillinger" through "Nixon" and "The Irishman" have proved, a story needn't be verifiable to offer truth of some sort (or illumination, or provocation, or just excitement). The problem is that—as Random House figured out—once you strip away Frey's initial promise of a true story, you're left with something that feels like a petulant, boastful, and not very noteworthy variation of a story that plenty of films, documentary and fiction, have told before, but with more insight or panache.

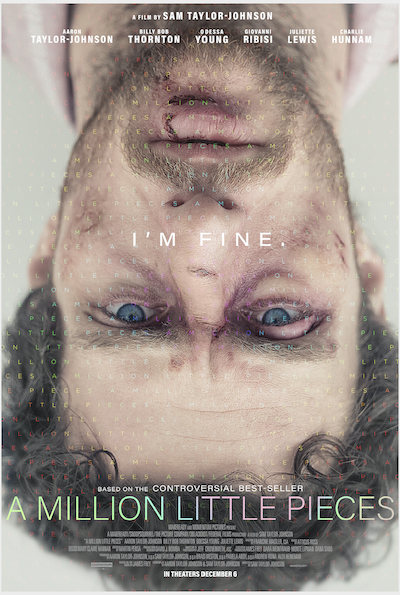

The movie is directed, confidently if a tad too slickly, by Sam Taylor-Johnson, and anchored by her husband Aaron Taylor-Johnson, in a soul-and-body baring lead performance as James Frey, a crack addict, alcoholic and all-around disaster who gets packed off to a rehabilitation clinic after falling from a balcony during a drug binge and busting up his face.

Once he's inside, he meets variations of characters who are familiar from other fiction films (and TV drama episodes, and novels, and memoirs) about recovery in a private facility, such as the tough but compassionate counselor (Juliette Lewis) who unlocks a childhood trauma that explains everything, and the terse but wise African-American roommate and sorta-mentor (Charles Parnell, playing a character named, I kid you not, Miles Davis), and the world-weary, droll, compassionate older white dude (Billy Bob Thornton) who refuses to give up on the young hero, no matter how petulantly he derides the twelve step program, mocks God, and insists he'd rather walk out and start doing drugs again. There's also a beautiful young female patient named Lily (Odessa Young) who feels rather like the rehab drama version of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl: the life force who reawakens the hero's dormant sense of possibility. And, regrettably, there's a wild-eyed, effeminate, predatory patient who unnerves and menaces James (a lisping, hand-waving Giovanni Ribisi—did no one involved with this production have the nerve to suggest that this character was a bad idea, and Ribisi's performance a worse one?).

Despite the source being stained by Frey's exposure as a fabulist, it's easy to see why the Taylor-Johnsons fought to get this film version made anyway. In terms of directorial and acting demands, it's what's known as a star vehicle, or a showpiece. The emotions are raw and big, and the constant threat of humiliation, injury and death marks the project as the opposite of today's go-to mode of American entertainment, the smirky, kid-friendly fantasy. The star suffers like a Mel Gibson martyr, the world beating the tar out of him every five minutes as karmic punishment for his tragic misjudgments and refusal to see his situation clearly. The tale begins with a drug-fueled nude dance and gets more flamboyantly masochistic as it goes. There are multiple injuries and doctor's visits, hallucinations and scatological situations (including a dance in a shit-filled hallway), a clumsy fight in a shower, and a scene of gory dental surgery.

In the end, though, there's no much to distinguish this story from similar efforts, from "28 Days" and "Permanent Midnight" though last year's "Beautiful Boy" and this year's "Honey Boy." You can feel the oppressive weight of the subgenre's more tiresomely common elements, from the contemplative yet hardboiled voice-over narration to the gradually expanding flashback revealing a terrible event to the scene where the hero gets a pen and some paper and starts cathartically writing the book that will become the movie you're watching.

The director is right to insist that it doesn't matter, for storytelling purposes, if any part of the tale is factually true. What's important is that the film doesn't end up feeling like a set of minor variations on the usual. But that, unfortunately, is where "A Million Little Pieces" ultimately lands. It's the kind of film where you start trying to guess which of the characters will turn out to be a figment of the narrator's imagination. The answer, of course, is all of them.