John Krasinski's "A Quiet Place" is a nerve-shredder. It's a movie designed to make you an active participant in a game of tension, not just a passive observer in an unfolding horror. Most of the great horror movies are so because we become actively invested in the fate of the characters and involved in the cinematic exercise playing out before us. It is a tight thrill ride—the kind of movie that quickens the heart rate and plays with the expectations of the audience, while never treating them like idiots. In other words, it's a really good horror movie.

With his script, co-written by Bryan Woods and Scott Beck, Krasinski wastes no time. We see a family—Krasinski plays the unnamed father, his real-life wife Emily Blunt plays the mother, and Noah Jupe ("Suburbicon"), Millicent Simmonds ("Wonderstruck"), and Cade Woodward play their three children. The eldest, the girl, is deaf (as is the remarkable young actress who plays her). A title card says it's "Day 89," and we can tell we're in a recently-post-apocalyptic world. The family very slowly—on tiptoes—moves around a small-town store, taking some of the few remaining supplies and some prescription drugs for the older boy, who looks like he has the flu. They communicate in sign language and are incredibly careful not to make a sound, but the youngest boy draws a picture of a rocket on the floor—the thing that he signs will take them all away.

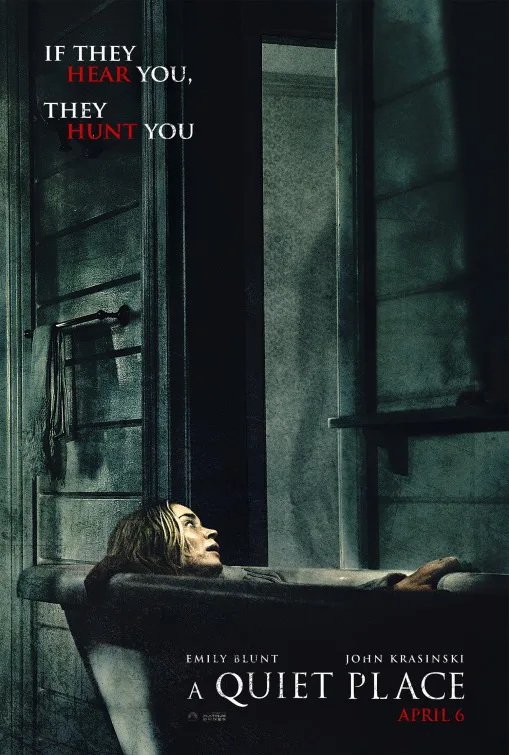

We quickly discern that sound in this world is dangerous. And the danger is intensified in the following sequence as the youngest child finds a toy that makes noise and ... things don't end well. The bulk of "A Quiet Place" takes place over a year later, as the family continues to grieve and the mother is about 38 weeks pregnant. Preparing for the arrival of a newborn baby in a world without noise is difficult, and the father continues to pore over newspaper articles and research, looking for a way to stop the creatures that kill at the slightest sound.

Larger-than-life enemies that can detect their prey aurally have been a part of great cinema for years, from the xenomorph hunting the crew of the Nostromo in "Alien" to the dinosaurs of "Jurassic Park," and Krasinski knows that lineage. He's incredibly smart about the way he brings the viewer into this auditory game. He's regularly—but not too regularly—setting up what could be called 'auditory expectations.' He'll show us a shotgun or an exposed nail in the floor or a timer in silence—and we know full well what sounds those are likely to produce. Don't worry—Krasinski doesn't overplay it at all. There aren't rooms of wind chimes or broken glass. It's a very subtle, clever storytelling tool to build tension when a director and his co-screenwriters aren't allowed to use dialogue to do so, and it pulls us into this world in a way that's unexpected and incredibly enjoyable.

It also helps that Krasinski displays a sense of composition and economic storytelling that he hasn't really before in other films. "A Quiet Place" is a no-nonsense, lean movie—the best kind when it comes to thrillers. It feels like every shot has been considered incredibly carefully as the film ticks like a clock on a bomb, perfectly balancing scares with scenes that set up the emotional stakes and the world of these characters. The film has a beautiful sense of geography, almost all of it taking place on a farm that Krasinski and his technical team lay out in a way that allows us to feel like we know it. This is not one of those films that mistakes shaky camerawork for horror storytelling. It's got a refined visual language that plays beautifully with perspective and the terrifying nature of a world in which we can't yell to warn/find people or, in the case of the deaf daughter, hear what's coming.

On that note, there's also—without spoiling anything—a strong, enabling message at the core of "A Quiet Place." It's a film that's about empowerment more than sheltering, and it's that emotional hook that really elevates the final act. It helps a great deal that Krasinski completely sticks the landing. It has one of the best final shots in horror in years—and, of course, it comes with a familiar auditory cue that had the audience here at SXSW cheering.

With almost no dialogue, "A Quiet Place" relies a great deal on visual storytelling, but I'll admit that it also uses the crutches of composer Marco Beltrami's strings for jump scares a bit too much. It's total conjecture, but one can almost sense Platinum Dunes head Michael Bay insisting on those devices, and I'd love to see a version of "A Quiet Place" that's even sparser in terms of on-the-nose choices like sound-scares and an overheated score.

We live in a such a noisy world that it's hard to imagine that constant sound being taken away. We use noise to express ourselves—it's a part of who we are as people. And "A Quiet Place" weaponizes that part of the human condition in a way that owes a debt to films like "Alien" but also charts its own new ground. So many great horror films are about people who have to adapt to survive—they have to challenge their own insecurities or preconceptions to make it through the night. In that sense, great horror films are often about empowerment, taking away that which some might perceive as weak. "A Quiet Place" shreds the nerves, but it does so in a way that feels rewarding. You don't just walk out having experienced a thrill ride, you walk out on a high, the kind of high that only comes from the best horror movies.

This review was filed from the World Premiere at the SXSW Film Festival in Austin on March 10, 2018.