"A Wolf at the Door," the first feature by Brazilian filmmaker Fernando Coimbra, is a strange animal: in one moment, it makes us laugh at one character's despair; one scene later, it provokes horror and makes us cringe when that same character acts to address the issue that was disturbing him/her. Balancing itself with an enviable self-assurance between drama, comedy, character study, and, in the last ten minutes, suspense, the film sends the audience out of the theater with a sense of shame for laughing when the narrative wanted us to.

Written by the director himself, the story begins when Sylvia (Nascimento) goes to the kindergarten that her little daughter (Ribas) attends in order to pick her up and discovers that the girl had already left with a "neighbor". Unable to imagine why someone would kidnap the child, as her parents are not wealthy, the desperate woman tells the police that her husband may have a mistress—and soon the man, Bernardo (Cortaz), confirms that he had maintained an affair with the young Rosa (Leal). From then on, the detective in charge (Cazarré) interrogates the three of them, gradually uncovering what really happened that day.

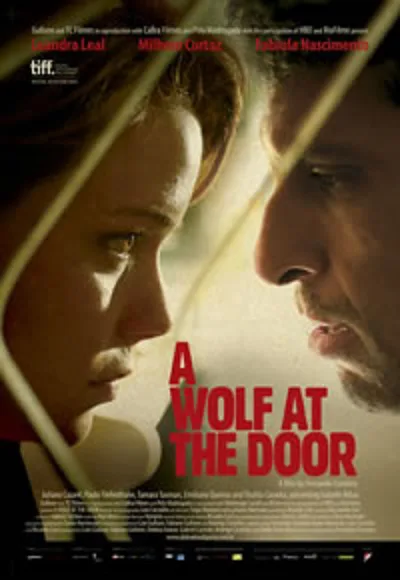

Surprisingly extracting humor out of a incredibly serious and dramatic situation, the film is especially benefited by the flawless performances of Leal, Cortaz and Nascimento. While the latter evokes not only concern about her daughter, but also impatience with her husband during flashbacks in which she begins to suspect about his affair, Milhem Cortaz, who usually plays thugs/tough guys, turns Bernardo into a pathetic, weak and desperate man, managing to simultaneously makes us laugh at his situation and also understand the seriousness of what is happening to him.

Still, "Wolf at the Door" really belongs to Leandra Leal, who creates a character whose transformation over the course of the movie is extremely impressive—beginning as a casual flirt and slowly turning into an absolute obsession while going through restrained passion and a growing feeling of frustration and anger. Never losing sight of Rosa's emotional and psychological trajectory, the beautiful actress particularly impresses in a scene where she, after being battered by her beloved one, surrenders to tears and to a nervous tremor that reveals her fear and her pain. Leal has always been a wonderful actress, but here she proves deserving to be on a list of the greatest Brazilian performers (and I didn't event mention her work during the final act, during which she makes "Fatal Attraction"'s Glenn Close look like Amelie Poulain—without ever turning into a caricature).

Lensed by the always competent Lula Carvalho in a claustrophobic way in tight shots that almost always glue us to the faces of the actors, the film also uses a sad and somber palette that gradually becomes suffocating. Moreover, the narrative benefits from shots that communicate the atmosphere of the story without the need for dialogue. When Bernardo appears on the left edge of the frame, looking at something out of the shot and seeming to be cornered while Rosa watches him from the bottom right, we realize the dynamic between those two individuals unequivocally. Meanwhile, Fernando Coimbra is able to create small camera movements that manage to expose the little moments of truth under the lie during the "alternative" (better yet: incomplete) versions of the stories told by each character.

Without making any concessions in its final act, which bravely respects the inevitable development of its characters' actions and temperaments, "Wolf at the Door" is a remarkable film that introduces Fernando Coimbra as a filmmaker to be closely monitored.