"After Hours" approaches the notion of pure filmmaking; it's a nearly flawless example of -- itself. It lacks, as nearly as I can determine, a lesson or message, and is content to show the hero facing a series of interlocking challenges to his safety and sanity. It is "The Perils of Pauline" told boldly and well.

Critics have called it "Kafkaesque" almost as a reflex, but that is a descriptive term, not an explanatory one. Is the film a cautionary tale about life in the city? To what purpose? New York may offer a variety of strange people awake after midnight, but they seldom find themselves intertwined in a bizarre series of coincidences, all focused on the same individual. You're not paranoid if people really are plotting against you, but strangers do not plot against you to make you paranoid. The film has been described as dream logic, but it might as well be called screwball logic; apart from the nightmarish and bizarre nature of his experiences, what happens to Paul Hackett is like what happens to Buster Keaton: just one damned thing after another.

The project was not personally developed by director Martin Scorsese, who was involved at the time in struggles over "The Last Temptation of Christ." Paramount's abrupt cancellation of that film four weeks before the start of production (the sets had been built, the costumes prepared) sent Scorsese into deep frustration. "My idea then was to pull back, and not to become hysterical and try to kill people," he told his friend Mary Pat Kelly. "So the trick then was to try to do something."

After rejecting piles of scripts, he received one from producers Amy Robinson and Griffin Dunne, who thought it could be made for $4 million. It had been written by Joseph Minion, then a graduate student at Columbia, and Scorsese was later to recall that Minion's teacher, the Yugoslavian director Dusan Makavejev, gave it an "A." He decided to make it: "I thought it would be interesting to see if I could go back and do something in a very fast way. All style. An exercise completely in style. And to show they hadn't killed my spirit."

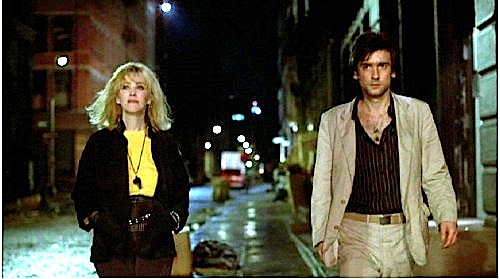

It was the first film of his what would become his long collaboration with German cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, who had worked with Fassbinder and therefore knew all about low budgets, fast shooting schedules and passionate directors. It was shot entirely at night, sometimes with on-the-spot improvisation of camera movements, as in the famous shot where Paul Hackett (Dunne), the hero, rings the bell of Kiki Bridges (Linda Fiorentino) and she throws down her keys, and Scorsese uses a POV shot of the keys dropping toward Paul.

In pre-digital days, that really had to happen. They tried fastening the camera to a board and dropping it toward Paul with ropes to stop it at the last moment (Dunne was risking his life), but after that approach produced out-of-focus footage, Ballhaus came up with a terrifyingly fast crane move. Other shots, Scorsese said, were in the spirit of Hitchcock, fetishizing closeups of objects like light switches, keys, locks and especially faces. Because we believe a close-up underlines something of importance to a character, Scorsese exploited that knowledge with unmotivated closeups; Paul thought something critical had happened, but much of the time it had not. In an unconscious way, an audience raised on classic film grammar would share his expectation and disappointment. Pure filmmaking.

Another device was to offhandedly suggest alarming possibilities about characters, as when Kiki describes burns, and Paul finds a graphic medical textbook about burn victims in the bedroom of Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), the girl he has gone to meet at Kiki's apartment. Are the burns accidental or deliberate? The possibility is there, because Kiki is into sadomasochism. Trying to find a shared conversational topic, Paul tells Marcy the story of the time he was a little boy in the hospital and was left for a time in the burn unit, but blindfolded and warned not to remove the blindfold. He did, and what he saw horrified him. Strange, that entering the lives of two women obsessed with burns, he would have his own burn story, but coincidence and synchronicity are the engines of the plot.

"After Hours" could be called a "hypertext" film, in which disparate elements of the plot are associated in an occult way. In "After Hours," such elements as a suicide, a method of sculpture, a plaster of Paris bagel, a $20 bill and a string of burglaries all reveal connections that only exist because Paul's adventures link them. This generates the film's sinister undertone, as in a scene where he tries to explain all the things that have befallen him, and fails, perhaps because they sound too absurd even to him. One thing many viewers of the film have reported is the high (some say almost unpleasant) level of suspense in "After Hours," which is technically a comedy but plays like a satanic version of the classic Hitchcock plot formula, the Innocent Man Wrongly Accused.

With different filmmakers and other actors, the film might have played more safely, like "Adventures in Babysitting." But there is an intensity and drive in Scorsese's direction that gives it desperation; it really seems to matter that this devastated hero struggle on and survive. Scorsese has suggested that Paul's implacable run of bad luck reflected his own frustration during the "Last Temptation of Christ" experience.

Executives kept reassuring him that all was going well with that film, backers said they had the money, Paramount green-lighted it, agents promised it was a "go," everything was in place, and then time after time an unexpected development would threaten everything. In "After Hours," each new person Paul meets promises that they will take care of him, make him happy, lend him money, give him a place to stay, let him use the phone, trust him with their keys, drive him home - and every offer of mercy turns into an unanticipated danger. The film could be read as an emotional autobiography of that period in Scorsese's life. The director said he began filming without an ending. IMDb claims, "One idea that made it to the storyboard stage had Paul crawling into June's womb to hide from the angry mob, with June (Verna Bloom, the lonely woman in the bar) giving 'birth' to him on the West Side Highway." An ending Scorsese actually filmed had Paul still trapped inside the sculpture as the truck driven by the burglars (Cheech and Chong) roared away. Scorsese said he showed that version to his father, who was angry: "You can't let him die!"

That was the same message he had been hearing for weeks from Michael Powell, the great British director who had come on board as a consultant and was soon to marry Scorsese's editor, Thelma Schoonmaker. Powell kept repeating that Paul not only had to live at the end, but to end up back at his office. And so he does, although after Paul returns to the office, close examination of the very final credit shots show that he has disappeared from his desk.

"After Hours" is not routinely included in lists of Scorsese's masterpieces. Its appearance on DVD was long delayed. On IMDb's ranking of his films by user vote (a notoriously unreliable but sometimes interesting reflection of popular opinion), it ranks 16th. But I recall how I felt after the first time I saw it: wrung out. Yes, no matter that it was a satire, a black comedy, an exercise in style, it worked above all as a story that flew in the face of common sense, but it hooked me. I've seen it several times since, I know how it ends, and despite my suspicion of "happy endings," I agree that Paul could not have been left to die. I no longer feel the suspense, of course, because I know what will happen. But I feel the same admiration. "An exercise completely in style," Scorsese said. But he could not quite hold it to that. He had to make a great film because, perhaps, at that time in his life, with the collapse of "The Last Temptation," he was ready to, he needed to, and he could.

Based on the reconsideration in my book "Scorsese by Ebert."