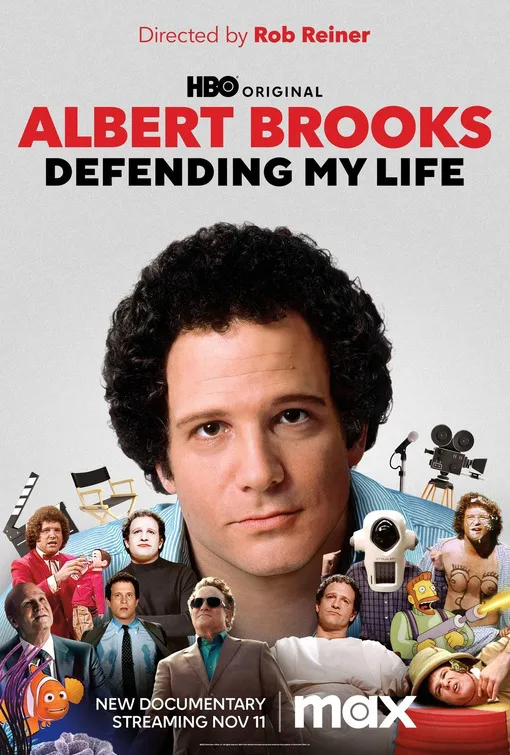

Albert Brooks has been one of the giants of American comedy for half a century. "Albert Brooks: Defending My Life" is a tribute to his talent and insight, directed by actor/filmmaker Rob Reiner, who met Brooks at Beverly Hills High School and has been his best friend ever since. Framed by a leisurely dinner between Brooks and Reiner at a Los Angeles restaurant, the movie follows Brooks from his early childhood in a showbiz family through his years as a standup comic, a short filmmaker on "Saturday Night Live," a writer/director/star of film comedies (including "Real Life," "Modern Romance," and "Lost in America"), and a character actor in other people's movies and TV series (including "Taxi Driver," "Drive," "Out of Sight," "Curb Your Enthusiasm," and "Broadcast News," which got Brooks an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actor).

This is not a detached, analytical work, nor does it try to be. It's the movie equivalent of a memorial service for a beloved individual who's still alive—a concept that Reiner makes official by quoting from a "Curb Your Enthusiasm" episode wherein Brooks (playing himself) is the subject of such a tribute, then is exposed as a hoarder of Covid-related supplies and ostracized—a twist worthy of one of Brooks' comedy routines or movie scripts, which often take a familiar comic concept and turn it inside-out or upside-down. "Curb" creator and star Larry David is one of many famous colleagues who appear onscreen as expert witnesses to Brooks' influence on their own work.

There's a consensus that what Brooks did at every stage of his career was so fresh and unique that there was nothing to compare it to. The movie's best achievement is arranging the pieces of Brooks' life and art so that we can see not just the consistently high quality of it all but Brooks' creative integrity as he moved through it. Brooks (who was born Albert Einstein; yes, really) insisted on doing everything his way, not out of defiance or pure ego, but because, as he explains it, alternatives never occurred to him. "I only saw one road!" he exclaims.

In the mid-70s, for instance, Brooks met with Lorne Michaels, who thought Brooks' exuberant conceptual comedy was a perfect fit for his new live sketch show "Saturday Night Live" and asked him to host it. Brooks told Michaels that it would be more fun and interesting to have a new host every week, something that had never been done before. Rather than join the "SNL" cast as a performer, Brooks asked if he could show short films that he'd made, which retrained his fan base to think of him as a filmmaker and positioned him to leap to full-length theatrical movies.

Brooks' debut feature, "Real Life," was the first in a string of four classic Brooks films: a satire on documentary ethics about a director (Brooks) who starts out trying to capture the life of a suburban family with his film crew but immediately begins interfering in it because he wants the result to be more exciting and commercial. Released in 1978, three years after "SNL" debuted, "Real Life" predicted what we now think of as "reality TV." It got strong reviews and is now recognized as groundbreaking but was abandoned by its distributor and bombed at the box office, perhaps partly because its hero was an obsessive, manipulative, increasingly unhinged person, and the other characters got swallowed up by his twisted values.

Brooks kept doing that throughout his career: doing what seemed best for the work, even if it made audiences and backers uncomfortable and closed off more lucrative avenues. Brooks' follow-up, "Modern Romance," is gentler but just as bleak: one of the great studies of romantic and sexual obsession, it's about a couple that keeps breaking up and getting back together even though they make each other miserable. If you squint a bit, you can see the influence of "Taxi Driver," the Martin Scorsese film from six years earlier in which Brooks played a campaign worker in love with a colleague played by Cybill Shepherd; that role also feels like a bit of a dry run for Aaron Altman in "Broadcast News," which was written for Brooks by his friend James L. Brooks (no relation).

He followed up "Modern Romance" with "Lost In America," about married yuppies who sell their house and buy a Winnebago to enact a safe version of their "Easy Rider" fantasy about seeing the real America, then lose their nest egg in Las Vegas and learn how most Americans actually live. Then came "Defending Your Life," an afterlife comedy which, as Brooks and others put it, is really about how hard it is to live without fear. Brooks, it seems, actually managed to do that, to some degree—although it meant that he never achieved superstar status and remained a "comedian's comedian," appreciated most fervently by other artists and fans of comedy that could seem weird, confusing, or uncomfortable if you weren't tuned into its wavelength.

Brooks became semi-famous as a high schooler when Rob Reiner's father, actor and filmmaker Carl Reiner, declared him one of the funniest people he'd ever seen. The movie gives us an account of a Brooks routine that impressed the elder Reiner: at a party, young Brooks presented himself as a master escape artist in the vein of Harry Houdini, then asked a guest to bind and gag him (by placing a napkin loosely over his wrists and a Kleenex wadded in his mouth), "imprisoned" himself behind a curtain, then began writhing and wailing about how he was trapped and was dying. A lot of Brooks' early comedy bits are like that: they take the germ of an old showbiz routine or trope and pull the guts out of it or twist it into a pretzel (as in the classic moment on the old "Tonight Show" with Johnny Carson where Brooks does "celebrity impressions" by eating different kinds of food). Incredibly, some of Brooks' best-known bits as a guest on talk and variety shows weren't rehearsed: he just thought them up in the dressing room before airtime. "Your brain has to work at a certain level to do comedy without trying it out," Chris Rock tells Reiner.

That reckless-seeming quality has always run beneath Brooks' art, along with a brainy, theoretical aspect that is difficult to unpack and scrutinize—although one sometimes wishes the film had tried harder to do so. The weakest element of "Defending My Life" is the parade of sound bites from other performers and filmmakers (including Chris Rock, Sarah Silverman, Conan O'Brien, and Jon Stewart) that needlessly fluff Brooks' reputation and repeat wearying variations of "he's a genius, he was so revolutionary, so amazing," or compare him to Chuck Yeager breaking the sound barrier or the like. It's not until confrontational standup comic Anthony Jeselnik shows up that we get a bit of real insight about what, exactly, Brooks' comedy was always about: "It was punk rock, almost, for comedy," he says of Brooks' earliest routines, especially the ones he did for Carson. "He saw what was going on, he saw the old Hollywood way, and instead of just saying 'this is bad, this is corny,' he showed them." The notion of Brooks as ground zero for the self-aware "anti-comedy" movement, which birthed everyone from Bill Murray and David Letterman (also an interviewee) through Silverman and the "Mr. Show" cast, is fascinating enough that it could be a film unto itself, but it's merely glanced at here.

Brooks offers simple explanations for work that his fans have analyzed within an inch of its life. He also describes "Lost in America" as a movie about "People who make gigantic decisions and are wrong," and "Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World"—released in 2005, in the midst of post-9/11 hysteria—as an attempt "to show that you could say the word 'Muslim' and not be killed." He's also generous in his praise for collaborators and colleagues (including his regular co-screenwriter Monica Johnson) and thoughtful in explaining why he waited so long to get married and have kids (with his wife Kimberly) and why he did it when he did it (at a certain point in one's love life, he says, you can just stop looking).

The sharpest insights about Brooks the man arrive in the sections about his parents, radio comic Harry Einstein, aka Harry Parke (who did Greek dialect comedy, as the immigrant character Parkyakarkus) and onetime musical comedy performer Thelma Reed (whom Einstein met on the set of a movie). Brooks' father was chronically ill and died onstage, literally, not figuratively, at a Friars' Club tribute in 1958 after performing a routine his son helped write. Brooks tells Reiner that after his father's death, he wanted to "cheat God" by using comedy to keep a barrier between himself and both his audience and the people in his life (something he didn't realize he was doing until the mid-70s when his career as a standup comic and recording artist was stagnating). The work got progressively more emotion-driven after that, peaking with the hopeful "Defending Your Life," the first Brooks film that made audiences cry at the end (and not because the characters were doomed).

The section about Brooks' film "Mother," starring Brooks as a successful novelist and Debbie Reynolds as his devoted but smothering and withholding mom, is another biographical jackpot. Brooks says it was about the belated realization that his mother's lack of interest in her son's success was a veiled expression of her resentment at having given up her own showbiz career to raise Brooks and his three brothers, something she must have felt keenly every day but didn't want to burden her boys with. (She did get some digs in, though: when Brooks told her that when he died, he wanted to be cremated, his mother replied, "Of course—I can tell by your cooking.")

This film will be a treat for anyone who loves any part of Brooks' career, or all of it. And its subject is so fascinating and open-hearted that one can imagine people who've never heard his name until now getting something out of it, too.

On Max on November 11th.