Film is the most voyeuristic medium, but rarely have I experienced this fact more sharply than while watching Woody Allen's "Another Woman." This is a film almost entirely composed of moments that should be private. At times privacy is violated by characters in the film. At other times, we invade the privacy of the characters. And the central character is our accomplice, standing beside us, speaking in our ear, telling us of the painful process she is going through.

This character is named Marion Post (Gena Rowlands), and she is the kind of woman who might feel qualified to advise the rest of us how to organize our lives by "balancing" the demands of home, job, spouse and friends. She is fearsomely self-contained, well-organized, sane, efficient and intelligent. "Another Woman" is about the emotional compromises she has had to make in order to earn that description.

She is the head of a university department of philosophy. She is married to a physician, and, childless, has a good relationship with her husband's teenage daughter from an earlier marriage. She dresses in a fashion that is so far above criticism as to almost be above notice.

She is writing a book, and to find a place free of distractions, she rents an office in a downtown building. She tells us some of these details on the soundtrack, describing her life with a dry detachment that sometimes seems to hide an edge of concern.

The office is in one of those older buildings with a tricky ventilation system. Sitting at her desk one day, Marion discovers she can hear every word of a therapy session taking place in the office of the psychiatrist who has his office next door. At first she blocks out the sound by placing pillows against the ventilation outlet. Then, frankly, she begins to listen.

While he is establishing this device of the overheard conversations, Allen does an interesting thing. Not only can Marion (and the rest of us) easily eavesdrop on the conversations, but when the pillows are placed against the air shaft, they completely block out every word. The choice - to listen, or not to listen - is presented so clearly that it is unreal. It's too neat, comprehensive, final.

Although most of the scenes in "Another Woman" are clearly realistic, I think the treatment of sound in the office is a signal from Allen that the office is intended to be read in another way - as the orderly interior of Marion's mind, perhaps. And the cries coming in through the grillwork on the wall are the sounds of real emotions that she has put out of her mind for years. They are her nightmares.

During the course of the next few weeks, Marion will find the walls of her mind tumbling down. She will discover that she intimidates people and that they do not love her as much as she thinks, nor trust her to share their secrets. She will find that she knows little about her husband, little about her own emotions, little about why she married this cold, adulterous doctor instead of another man who truly loved her.

If this journey of discovery sounds familiar, it is because "Another Woman" has a great many elements in common with Ingmar Bergman's "Wild Strawberries," the story of an elderly doctor whose day begins with a nightmare and continues with a voyage of discovery. The doctor finds that his loved ones have ambiguous feelings about him, that his "efficiency" is seen as sternness, and that he made a mistake when he did not accept passionate love when it was offered to him.

Allen's film is not a remake of "Wild Strawberries" in any sense, but a meditation on the same theme: the story of a thoughtful person, thoughtfully discovering why she might have benefitted from being a little less thoughtful.

There is a temptation to say that Rowlands has never been better than in this movie, but that would not be true. She is an extraordinary actor who is usually this good, and has been this good before, especially in some of the films of her husband, John Cassavetes. What is new here is the whole emotional tone of her character. Great actors and great directors sometimes find a common emotional ground, so that the actor becomes an instrument playing the director's song.

Cassavetes is a wild, passionate spirit, emotionally disorganized, insecure and tumultuous, and Rowlands has reflected that personality in her characters for him - white-eyed women on the edge of stampede or breakdown.

Allen is introspective, considerate, apologetic, formidably intelligent, and controls people through thought and words rather than through physicality and temper. Rowlands now mirrors that personality, revealing in the process how the Cassavetes performances were indeed "acting" and not some kind of ersatz documentary reality. To see "Another Woman" is to get an insight into how good an actress Rowlands has been all along.

I have not said much about the movie's story. I had better not.

More than with many thrillers, "Another Woman" depends upon the audience's gradual discovery of what happens. There are some false alarms along the way. The patient in the psychiatrist's office (Mia Farrow), pregnant and confused, turns up in the "outside" world of the Rowlands character, and we expect more to come of that meeting than ever does. Some critics have asked why the Rowlands and Farrow characters did not interact more deeply, but the whole point is that the philosopher has suppressed everything inside of her that could connect to that weeping, pregnant other woman.

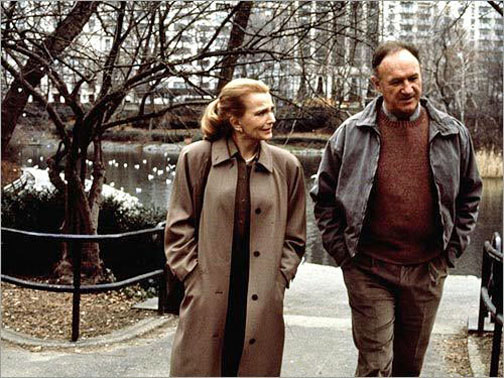

There is also an actual "other woman" in the film, as well as a dry, correct performance by Ian Holm as a man who must have a wife so that he can be unfaithful to her. Gene Hackman is precisely cast as the earlier lover whose passion was rejected by Marion, and there is another of Martha Plimpton's bright, somehow sad, teenagers. In the movie's single most effective scene, Betty Buckley plays Holm's first wife, turning up unexpectedly at a social event and behaving "inappropriately," while Holm firmly tries to make her disappear (this scene is so observant of how people handle social embarrassment that it plays like an open wound.) The death of John Houseman lends poignancy to his appearance as Marion's father. In this last performance, Houseman finally cut loose from all of the appearances of robust immortality and allowed himself to be seen as old, feeble and spotted - and with immense presence. (In a scene involving the character when he was younger, David Ogden Stiers makes an uncanny Houseman double.) "Another Woman" ends a little abruptly. I expected another chapter. And yet I would not have enjoyed a tidy conclusion to this material, because the one thing we learn about Marion Post is that she has got her package so tightly wrapped that she may never live along enough to rummage through its contents. At least by the end of the film she is beginning to remember what it was that she boxed up so carefully, so many years before.