"Antarctica: Ice and Sky," a documentary about the scientist whose research first called attention to anthropogenic climate change, ends with the sort of vague call to action that such works typically do. It's a simple question: "What are you going to do?" The challenge comes across as particularly hollow (perhaps even more so than, say, a plea to visit a website or send a text message, although not as pandering as those calls to action, which are meant to make a concerned viewer feel as if they have done something without doing anything of real impact). That is mostly because director Luc Jacquet has not made a work of direct activism. The last-minute attempt to turn the film into one is never earned.

The final question is a momentary misstep in a film that serves—perhaps unintentionally—as a subtle, almost subversive counterargument to those who would either deny the existence of human-made climate change or dismiss the evidence as some mild deviation from or normal part of the natural climate cycle. The arguments of such people usually rest on the notion that the science is somehow faulty, that the scientists are simply in it for the money, or some other contention that calls into question the processes or integrity of the people who have done or studied the research.

Jacquet's film assembles decades of footage—from the mid-1950s to the 1980s—of scientists doing that research in the sub-zero temperatures of Antarctica. Seeing the work being done—as well as the conditions and dangers that went along with it—just about negates such arguments. These scientists whom we see throughout the film are not in it for fame or glory or money. Their research comes at great personal risk to life and limb, and the results are far too alarming for any of these men to have desired them in any way.

The central figure of the film is French glaciologist Claude Lorius, who has participated in 20 expeditions to the continent over the course of his life. He describes (through the voice of Michel Papineschi) the strange, unexpected course of career, as he essentially entered his field of study by accident and became one of its most esteemed forefathers.

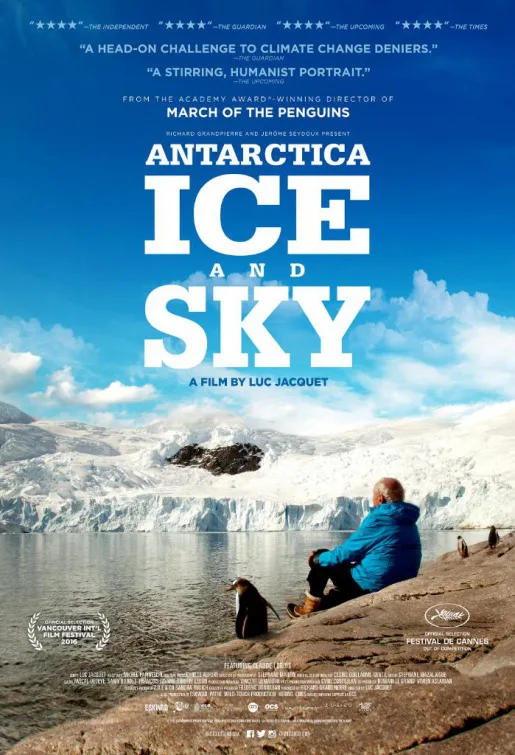

At the time of filming his segments, Lorius is 81 years old. He has been honored with multiple awards and has become a respected voice in the call to fight man-made climate change. Lorius, visiting the continent again for the documentary's production, sits and stands around a landscape that has visibly changed from the days of his work. Jacquet's camera makes a stunning sweep across that landscape in one shot, moving from Lorius, as he walks along some snowy terrain, to some barren, gray mountains. We can see the amount of snow lessen and lessen as the shot progresses, until it arrives at a valley where a stream of water trickles along.

We know this isn't right, because we see the continent over the course of three decades in the film's extensive archival footage. The majority of the film comprises this footage, as Lorius and his various expedition and research teams spend months on the frozen continent, traveling and sleeping in the cramped compartments of snow vehicles for days or weeks before arriving at slightly more spacious research stations. The temperatures are deadly (He relates the story of Russian researchers setting barrels of oil on fire so that the fuel would return to its liquid form). The vehicles must trek across hidden crevasses covered by snow and ice, and the detection equipment keeps failing. The wind blows down the mast above the underground station, forcing him to remove his gloves to manipulate the nuts and bolts of the structure to reassemble it.

Lorius' major breakthrough was the development of an ice corer that would eventually retrieve ice thousands of meters below the surface, which, in terms of a geological calendar, translates into hundreds of thousands of years of Earth's history. His most significant discovery—made by placing some ancient ice in celebratory glasses of whiskey—was that the ice contained air from the era in which it was formed. Lorius, who made his first trip to Antarctica at the age of 23 primarily for the sense of adventure (The film's narration takes on a continuous tone of wonder), becomes a model of professional evolution—his work becoming a prime example of how the scientific method is often founded on happenstance.

Late in the film, Lorius wonders what his work, all of those awards, and the warnings he and other have made actually mean when those warnings go unheeded. In the film's final montage, he receives his accolades amidst international conference after international conference that has done little to nothing in the grand scheme of things—the only way a man such as Lorius, who has spent most of his life studying climatic life of our planet, can see such issues. If anything, the film's primary argument is that we have lost the ability to see that perspective. Regaining that perspective is the start of our only chance.

As "Antarctica: Ice and Sky" shows us, it is possible. As a result of Lorius and his team discovering that they could accurately date every nuclear weapon test from radioactive material found in Antarctic ice, there was an international treaty banning such tests, with over 100 nations signing on to it. Lorius' most important work was conducted as a collaboration between France, the United States, and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. If the people of that time could put their ideological differences aside in recognition of the gravity of such research, surely we can do the same.