In Sam Levinson's needlessly self-serious "Assassination Nation," a gruesome, modern-day spin on the 17th century Salem witch trials by way of Mean-Girls-Gone-Wild, the central character Lily is an 18-year-old, opinionated high-school senior with a zero-f*cks-given attitude. She wears "Fatal Attraction" socks for kicks and sports kiddies' arm floats at the pool for no apparent reason. Her aura of indifference is so extreme that when she's rightfully called into the principal's office to answer for her pornographic class drawings, she shrugs it off at first. Then she launches into a feminist defense of her art as an expression of how hard it is for women to exist in the misogynistic ranks of the selfie-obsessed social media. "It's not about the nudity," she explains to her genuinely inquisitive teacher. "It's about the thousands of naked selfies you took to get just one right."

Her principal (Colman Domingo) lets her off the hook with a gentle warning and an insinuation that she might just be a beyond-her-years genius. But if I'm being honest, even after hearing Lily's lengthy justification twice, I am no closer to understanding her argument than I am to appreciating the messiness of the film that surrounds it. It's not that Lily is wrong—social media is sexist and toxic and guilty of setting impossible standards and every damning thing in-between. She is on the right track in articulating that (in this key scene and others) nudity doesn't automatically equate to sexuality. It's that her drawings don't make a sound point in the ballpark of her appeal. Like "Assassination Nation" itself, Lily clearly has a lot on her mind concerning our faux existence online. But neither she nor the miscalculated film that centers on her seems to have any clue as to how to grapple with critical thoughts in full-fledged statements. In that, "Assassination Nation" serves more like a checklist of grave topics that exclusively speaks, like Lily does, in shallow buzzwords without giving any of its themes the depth they deserve.

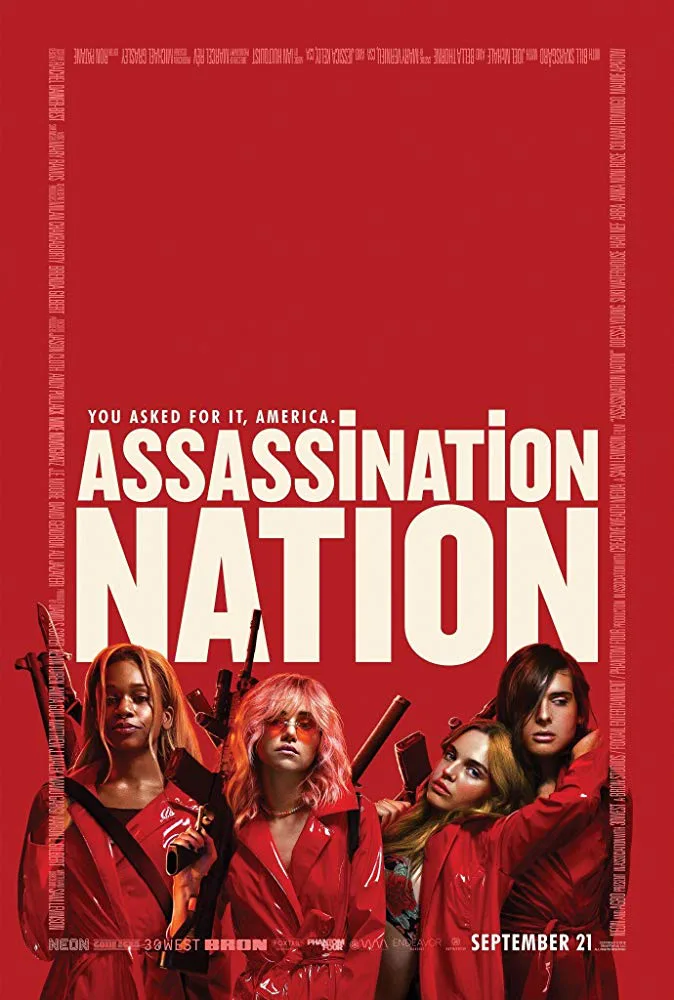

And right from the start, Levinson's film grants itself the permission to do exactly that—be a free-for-all table of contents that says close to nothing. The narrator Lily (a brave Odessa Young) gives us a trigger warning before she tells the tale of how her town Salem (get it?) lost its "motherf*cking mind" (her words, not mine). She indicates we'll be exposed to sexism, racism, homophobia, male gaze, swearing, rape attempt, blood, guts and all-things-awful imaginable in her tale of overnight survival that also involves her three best friends: Bex (Hari Nef), Sarah (Suki Waterhouse) and Em (Abra). And off we go: we laze with them during their philosophical gossip sessions, stroll with them in the inexplicably dark hallways and auditoriums of their school and get a feel for their superficial senior lives through feverish cinematography and a mind-numbingly busy soundtrack.

Meanwhile, we learn about Lily's anonymous sexting with a shady guy named Daddy—perhaps because it's dangerous, or self-assuring (or a little bit of both), she sends him her nude photos in exchange for suggestive compliments. The only problem is, an online vigilante seems to be on the loose in town, harboring a grudge against everyone crooked. Let the hacks begin! A dishonest conservative politician goes down first. Then the wholesome school principal unfairly faces the same fate. Exposing a village-wide digital Burn Book and spreading its pages like an online virus with irreparable consequences, the ruthless hacker finally lands on Lily, along with almost half the town of Salem. Eventually, Lily and her friends find themselves as the target of the town's frightening hatred and murderous acts. With that, the film instantaneously takes a turn towards the direction of "The Purge" as Salem's attacks on the girls intensify, launching a full-fledged thriller where our vengeful heroines unavoidably arm up.

Throughout "Assassination Nation," Levinson's visual range—recalling everything from Quentin Tarantino to ‘80s slasher films and even "American Beauty"—remains loud and unfocused with plenty of crimson red, split screens and showy slow-motion to go around. So hectically overdone in style that it already feels dated despite its timely leanings, Levinson's film vaguely shelters a compelling story about today's unforgiving online mob mentality beneath its convoluted layers. Despite the fact that he misses the mark on his good, feminist intentions and unfortunately introduces an accidental (yet all the same troubling) "good guys with guns" dimension into his story, Levinson does seem to have an undercooked thesis on contemporary mass hysteria. What a shame it gets drowned out by incessant noise in the end, which, like an online mob, attacks your senses from all directions.