Not knowing in advance that "Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn" begins with a few minutes of hardcore pornography, I made the mistake of starting it on a big television in a home containing teenagers. This is not advisable, as it could yield a scene similar to the one that transpired in my own house, with yours truly scrambling to find the remote control to lower the volume and then turn the picture off completely. "It's art!" I yelled to the rest of the house, whose denizens thankfully were concentrated on a different floor. "Art!"

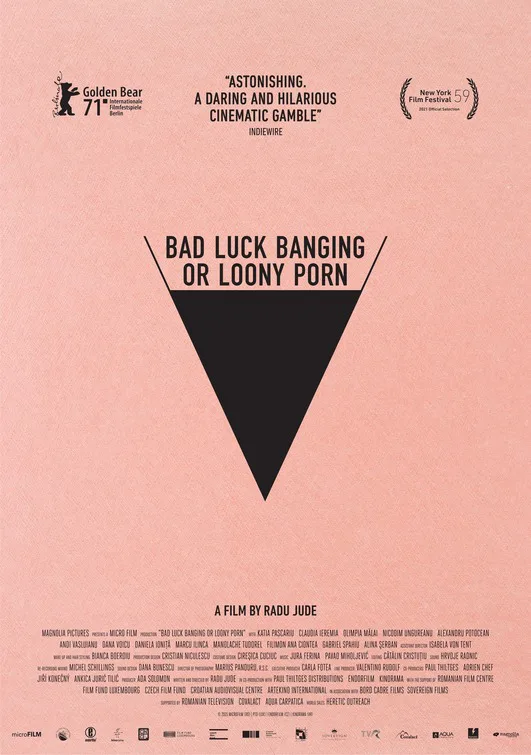

As it turns out, this is the sort of scene that could have appeared in this wry feature from Romanian director Radu Jude, which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. The main character is Emi Cilibiu (Katia Pascariu), a secondary schoolteacher who makes a porno video at home with her husband only to have it escape onto the Internet (as such videos tend to do).

The exact circumstances are a bit unclear—I think the husband uploaded the video to a private server, and some unknown third party downloaded it and put it up where the general public could see it—but for narrative purposes, they don't matter, because while the movie is concerned with whether Emi will lose her teaching job over the video (the entire film takes place in the lead-up to her inquisition) it's all just the means to an end: showing the contradictions and hypocrisies of Romanian society.

Jude goes about that task in the spirit of a filmmaker like Robert Altman or Richard Linklater, who often made so-called "network narratives" (a term coined by the great film scholar David Bordwell) that avoided conventional storytelling techniques and adopted more of a hanging-out approach, following a character or characters from one place to another, watching what happens during the journey or at the destination, then picking up those characters or others and following them to the next location.

Altman was especially good at settling on storytelling devices that would carry the viewer to the next point of interest, such as a roving sound truck in "Nashville" or the fleet of helicopters spraying Los Angeles to kill medflies in "Short Cuts." The equivalent here is Emi herself. Much of the film consists of shots of the heroine, dressed in the outfit that she's chosen for the inquest, traveling around Bucharest on foot, going to the market and then visiting sympathetic but concerned family members and eventually ending up at the hearing, which is conducted with appropriate social distancing because the film was shot on real locations during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Along the way there are encounters that subtly drive home the arrogance, entitlement and misogyny of men in this society. Emi confronts a driver whose vehicle is illegally parked up on a sidewalk, and avoids an older man who wants to give her a rose and make small talk.

It's unclear whether the latter approached her because he recognized her from the video or because that's just what clueless older men sometimes do, and this ambiguity, too, is not as important as the overall vibe of the movie, which somehow inexplicably feels like life. All around us are people who have seen and in some cases are actively watching pornography, and the porn is derived from currents within the culture that the filmmaker, er, lays bare, by watching his main character go about her mundane daily business.

Nearly all of the people Emi interacts with are oblivious to the effect that the video has had on her reputation and professional status. It's likely that those who even know about it don't think of her as a human being with an identity and the ability to exercise consent (which was ignored in this case) but rather as a body placed onscreen for their voyeuristic pleasure. (Would the film have been as effective without showing us the video? I can't decide.)

The movie feels scattered and meandering, not in a debilitating way: purposefully aimless. Sometimes the camera will follow Emi and then move away from her to capture another bit of business involving other people, such as the woman who looks right into the camera and invites the audience to eat her out (was this scripted, or simply an incident that occurred while filming in public?) or a pedestrian who's seen berating a motorist who nearly ran him over at a crosswalk and demanding that he go ahead and finish the job.

There are also many moments when the camera moves away from ground level entirely and prowls up the face of a storefront or apartment building, showing us the architecture. This might be a comment on the anonymity of big city life, or it might be that the camera operator just likes showing us the architecture.

This is a movie with an unconventional style that could be off-putting if you're not used to it, or if you're overly concerned that every screen moment reinforce whatever rhetorical points you think the film is making. It seems more likely that this is a film about discoveries rather than statements, with the camera following people and then abandoning them to seek insight elsewhere, by looking into things rather than merely looking at them.

In theaters today.