The title "Broken" most directly refers to families, but it's also an adequate assessment of the Rufus Norris's debut feature, an absorbing coming-of-age drama that suddenly, pointlessly self-destructs with an onslaught of cheap ironies and overkill. Until then, it's a tense portrait of three English homes, all clustered around the same cul-de-sac, and how one lie and an ensuing act of violence reverberate through the residents' lives.

Norris, a West End veteran, edits his film in an oblique, lyrical style that one associates more with David Gordon Green than with the stage. Events are sometimes seen slightly out of order, organized for impact rather than chronology. The catalyzing incident is seen first: As 11-year-old Skunk (a wonderful Eloise Laurence) looks on, her neighbor Mr. Oswald (Rory Kinnear) viciously beats Rick Buckley (Robert Emms), the frightened and mildly learning-disabled man who lives next door. Flashing back a few minutes, we learn that one of Mr. Oswald's daughters, Susan (Rosalie Kosky-Hensman), has falsely accused Rick of rape rather than confess to an innocent misunderstanding. Her father has found an opened condom wrapper in their home, mistaking it for a sign of her promiscuity. The matter is sorted out, but the damage is done. Traumatized Rick is sent to an institution, while Susan will go on to fool around the way her violent dad always feared.

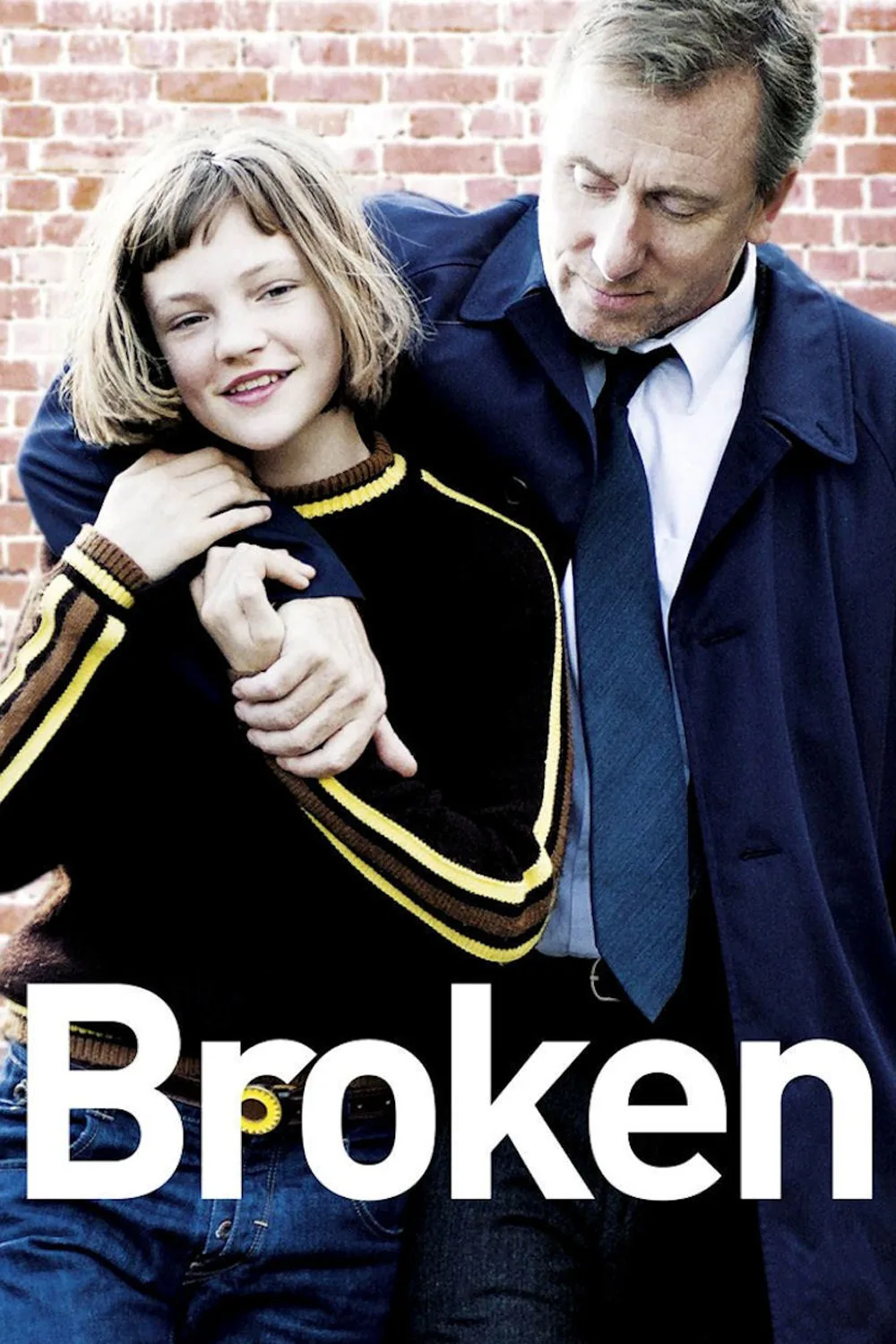

But back to Skunk: Children are impressionable, and the sight of the attack stays with her. She worries that Rick will suffer treatment along the lines of what she saw in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." Her own life is in flux, from a bourgeoning first love to anxiety over being bullied at a new school, where her nanny's commitment-fearing boyfriend (Cillian Murphy) works as a teacher. Skunk has Type 1 diabetes and monitors her blood sugar on her own. She has to be independent: Her mother walked out on the family, and her lawyer father (Tim Roth) raises them, perhaps slightly lovesick himself, as well as slightly wary of the brutish patriarch next door.

If it isn't obvious already—from the assonance of Skunk's name with Scout; the way Roth's solicitor is called on to defend the falsely accused; or the way Rick functions as a Boo Radley figure—"Broken" has been quite transparently conceived as an homage to "To Kill a Mockingbird," which author Daniel Clay, who wrote the novel on which the film is based, has acknowledged as an inspiration. At times the movie seems closer to full reworking than tribute, and there's a fascination in seeing a quintessentially American story transplanted to a British context. To the extent that "Broken" follows Harper Lee's template—observing a child's dawning awareness of the morally troubled world around her—it's quite good.

But context is key, and while Lee's masterwork turned an eye on 1930s Alabama, "Broken" doesn't show much interest in the world beyond the cul-de-sac. Dramatically, the film is a closed system, in which just about every major action prompts an unintended consequence, and the best intentions unfailingly go awry. In that sense, "Broken" owes more to didactic tapestry films like "Babel" than to one of the great works of 20th-century literature. Imagine "To Kill a Mockingbird" with multiple trumped-up medical emergencies and a cynically manipulative finale, and you might have a sense of how Norris's film plays by the end: broken, smashed, destroyed.