For anyone who complained that Yorgos Lanthimos went soft with "Poor Things" and "The Favourite," "Kinds of Kindness" revives the malicious tendencies that have coursed through even some of his best films. The movie reunites him with his early and frequent screenwriting collaborator Efthimis Filippou ("Dogtooth," "The Killing of a Sacred Deer"), and the shift in tone from the last two features is whiplash-inducing. "Kinds of Kindness" is not "Poor Things 2," and moviegoers who wander in expecting that are in for a nasty shock.

"Kinds of Kindness" is really three movies in one—the first two around 50 minutes in length, the third a little longer. The three segments share a cast (Emma Stone, Jesse Plemons, Margaret Qualley, Hong Chau, Willem Dafoe, Joe Alwyn), a few motifs, and a general philosophy of life that boils down to the idea that some people "want to be abused," as Annie Lennox sings in "Sweet Dreams," which immediately perked up my Cannes audience as it blared over the Searchlight logo.

But exactly how much abuse—and how many kinds of sorrow—can Lanthimos deadpan his way through in 164 minutes? Suicide, rape, domestic violence, vehicular homicide, animal cruelty, a miscarriage, forced abortions, cult brainwashing, self-amputation, police brutality: In "Kinds of Kindness," all of it just becomes stuff for Lanthimos to stage as if it's no big deal. His elegant tableaux are expertly framed, again, by the cinematographer Robbie Ryan. (The two still have a thing for wide-angle lenses, except this time they're shooting in widescreen, which gives the gimmick some new inflections.) Your mileage may vary, but at a certain point the casualness with which Lanthimos treats tragedy becomes far more disturbing than it is darkly funny. And in fairness, nobody said that "Kinds of Kindness" was supposed to be a comedy, although it's difficult to imagine what else it thinks it is.

A title card announces the first chapter, "The Death of R.M.F." Immediately, we're introduced to a man (Yorgos Stefanakos) who has those initials embroidered on his shirt. He's doomed! Or maybe it's a feint? Multiple characters in the segment turn out to have the initials "R.F.," including the protagonist, Robert (Plemons). Robert has outsourced every decision in his life to his boss, Raymond (Dafoe), who leaves him instructions on what books to read, what he ought to eat and drink, and even how often he's allowed to have sex. (Chau plays Robert's wife.)

Raymond insists on total obedience, no matter how bizarre his instructions or his actions. (One of the better running gags involves his habit of giving memorabilia from sports legends as gifts.) The premise has real potential that is sometimes realized, especially once Stone turns up as a woman called Rita. But the sheer cruelty of the punchline ends the segment on a sour note.

"R.M.F. Is Flying" fares better, partly because it's more equal-opportunity in its meanspiritedness. Plemons plays a police officer, Daniel, whose wife, Liz (Stone, by far the performer most on Lanthimos's wavelength), is suddenly located after having been thought lost at sea during a disastrous maritime research trip. How exactly did she survive? Daniel isn't convinced it's her. (Her feet are too big.) This time, it's the Plemons character who makes bizarre demands for shows of loyalty, and the pair's lives become a folie à deux.

"Kinds of Kindness" goes off the rails in "R.M.F. Eats a Sandwich," which casts Stone and Plemons as members of a cult (Dafoe and Chau play the leaders) searching for a woman whose attributes apparently match some sort of prophecy. Best not to say too much, except that, perhaps out of a need to up the outrage ante, Lanthimos seriously miscalculates when trying to devise a way for a character to run afoul of the cult. Nothing in "Kinds of Kindness" could be funny after…whatever it is that happens. And a lot of the film isn't so funny beforehand.

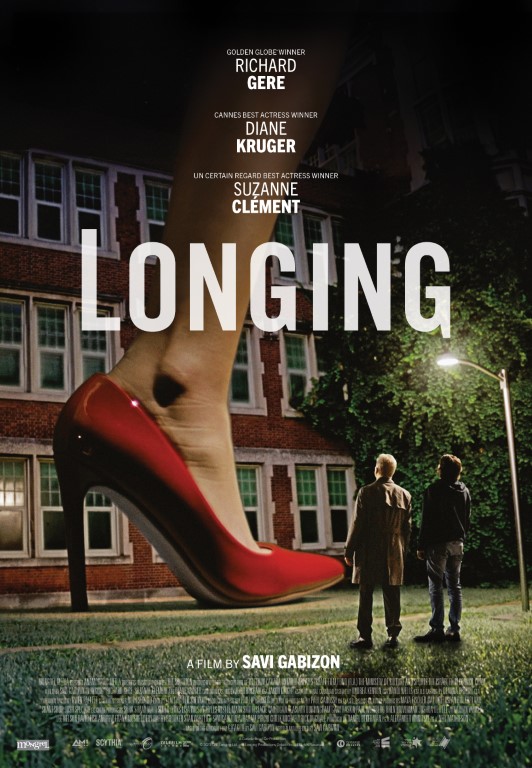

For sheer humorlessness, though, look to Paul Schrader's "Oh, Canada," his second adaption (after 1998's "Affliction") of a novel by Russell Banks, who died last year. "Oh, Canada" revolves around a dying documentarian, Leonard Fife (Richard Gere), who agrees to be interviewed for a film by two former students (Michael Imperioli and Victoria Hill). He sees it as more than an opportunity to simply share his story; he describes the interview as his "final prayer," a chance to confess to things he has never revealed. During shooting, his current wife (Uma Thurman) looks on from off-camera.

The American-born Fife is regarded as a hero in some circles for resisting the draft and fleeing to Canada. But the story of how he got there isn't simple, and Leo's memory isn't so good either. His recollections bounce around in time. That poses a dramaturgical challenge for Schrader, who has to deal with the fact that Leo, unsatisfyingly, doesn't finish many of the stories he starts.

Still, Schrader makes things even harder for himself with some dubious decisions—casting Thurman in dual roles, for instance, or having Gere crash his own flashbacks. Mostly young Leo is played by Jacob Elordi, but sometimes Gere himself will turn up in the memory scenes, which leads to awkward moments like the one in which old Leo converses in bed with young Leo's pregnant second wife (Kristine Froseth). And while Gere can be an underrated actor, his endless variations on "muttered anguish" made me wish, as they did in "Time Out of Mind" a decade ago, that someone would hand him an Oscar from off-screen just to put a stop to such self-conscious effort.

One film at Cannes truly qualifies as a final statement: Jean-Luc Godard's "Scénarios," an 18-minute short that ends with a scene that Godard filmed the day before his death by assisted suicide in 2022. Trying to distill late Godard into words is an impossible exercise, but the short, divided into two parts—"DNA, Fundamental Elements" and "MRI, Odyssey"—initially proceeds in the same storyboards-in-motion mode seen in last year's "Trailer of a Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars." There are bold colors; serene, sliding movements; and (once it kicks in) a densely layered sound design.

In the "MRI" half, though, as MRI-like scanning noises play intermittently on the soundtrack, the film takes a turn for the concrete: It culminates in a montage of death-haunted scenes from some of Godard's own movies ("Band of Outsiders," "Contempt," "Weekend") and from other films by directors he admired (Howard Hawks's "Only Angels Have Wings," Roberto Rossellini's "Open City"). Then there is a shot of Godard, sitting on a bed reciting a text about "fingers and non-fingers" that first surfaced in the "DNA" strand. The text, according to the press notes, is from Sartre. Godard concludes it with a sendoff that I won't spoil.

In what turned out to be an extraordinarily moving double bill, "Scénarios" was shown with another, longer short, "Exposé du Film Annonce du Film 'Scénario'" (pictured), filmed 11 months earlier. In it, Godard—over what, unless I missed a cut, appeared to be an uninterrupted 36-minute shot—explains his notes on the film as they exist at that point to his collaborators Jean-Paul Battaggia and Fabrice Aragno. The second short offered a rare opportunity to watch Godard at work—and to see just how carefully his late films were planned. There is, he admits, "one last image that doesn't mean anything."