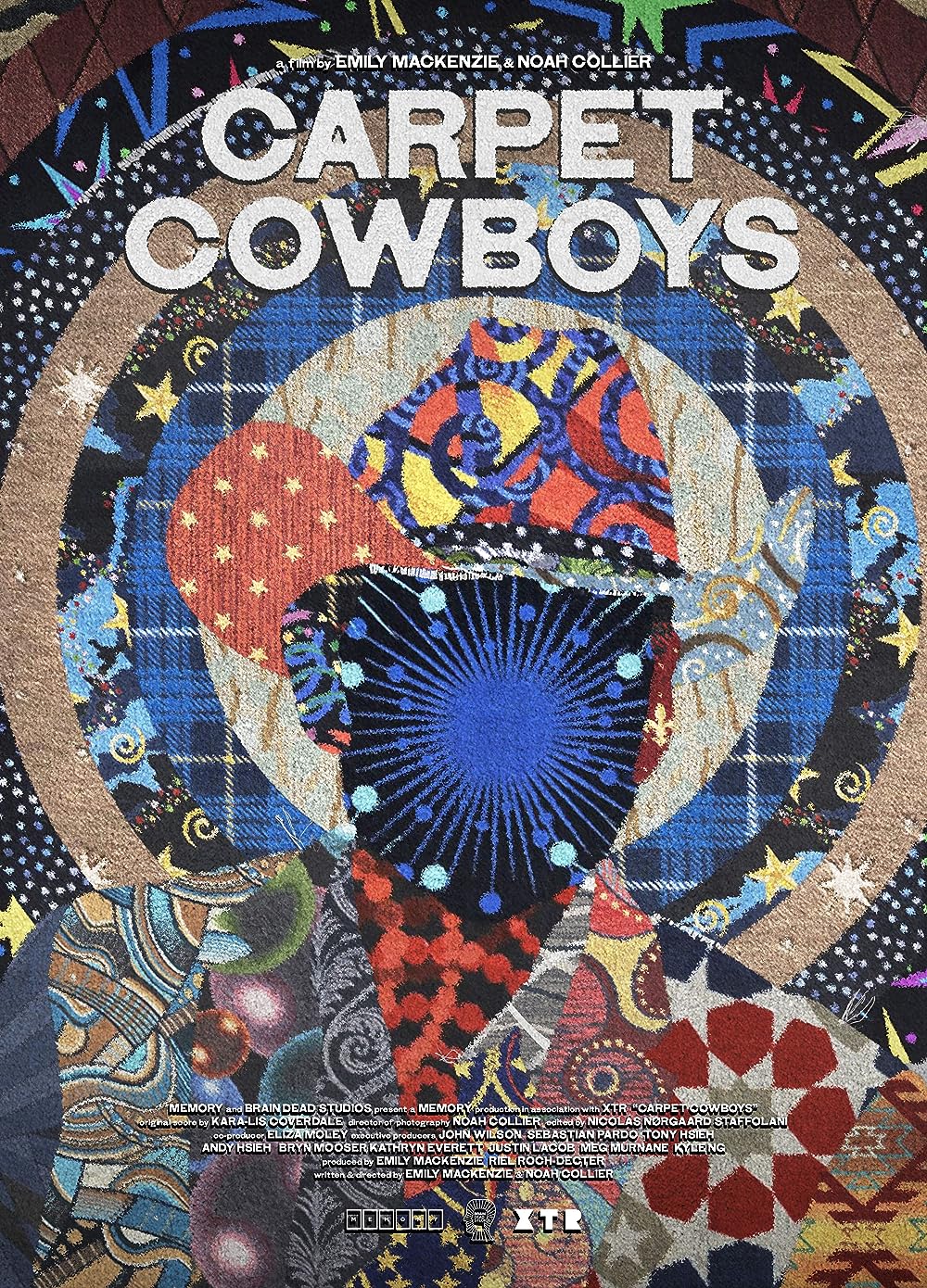

You may never have heard of Dalton, Georgia, but you've probably touched a piece of it. Eighty-five percent of carpets in the United States come from the small town in northern Georgia, known as the "Carpet Capital of the World." At first, it seems "Carpet Cowboys," the debut documentary from co-directors Emily MacKenzie and Noah Collier, intends to merely tell the unsung story of this niche industry and the quirky artists, businessmen, and scientists who earn their living working in it. But the filmmakers use it as a launching pad to chart the deconstruction of the American Dream.

MacKenzie and Collier set the scene with evocative imagery of the complex machinery that makes these carpets, weaving thousands of threads into the banal tapestries we traipse upon every day. "It is the canvas on which all the other art rests," says Lew Migliore, one of the many colorful figures whose livelihood is found in the flooring world. There's also father and son Doug and Lloyd Caldwell, who've helped run a family carpet business for over 50 years. Introduced sitting in front of a bold, swirly red-hued carpet, Lloyd laughs, remembering how "this industry was really put together by north Georgia hillbillies and half of them couldn't read or write."

There's also freelance textile designer Roderick James, a Scottish expat who loves the country lifestyle—emphasis on style—and his partner Jon Black, a musician who writes jingles. While MacKenzie and Collier weave all these story threads together to craft a whole picture of this industry in crisis, Roderick and Jon's story pops, like the overarching pattern in one of the carpets he designs.

Early on in "Carpet Cowboys," Jon takes the filmmakers on a drive, pointing out where one corporation displaced 36 houses, including a "cute little house" owned by his mother's family and a tree he played in as a kid that was completely dosed to make way for a parking lot. Yet he says although this destruction took away homes, it brought work. "It's just part of a cycle," he says, as footage of an empty lot fills the frame. What could be bleaker than a cycle that creates jobs but destroys homes? At least Arthur Miller's Lomans had a job and a house.

The rise of corporate consolidation and deregulation of monopolies puts the small, family-run businesses out of work. Lee Philips, whose job involves stress testing and stain resistance science, points out that during the industry's heyday, there were around 480 mills within 25 miles of Dalton, but by the 1990s, it was down to about a dozen. With the loss of small businesses, so, too, came the loss of the camaraderie found within this community. While some in the business are still passionate, like Doug, who can pick out his favorite pattern amongst the thousands of rugs in his showroom, most of the companies left are faceless corporations whose only passion is profit margins.

This consolidation also makes the life of freelance artists like Roderick that much more perilous. When we first meet him, he's wearing a white Stetson and an American flag scarf, photographing the tree bark pattern, showing Jon how it could be turned into a textile. Roderick is the kind of larger-than-life character with a hint of melancholy that makes a documentary like this soar. That Roderick is also a literal embodiment of the American Dream turned sour makes the documentary's themes all the more poignant. As Roderick, who emigrated from Scotland in 1985 to pursue his textile dreams, navigates this now-broken economy, he muses, "I really don't know where America's going right now. I thought I did."

Perhaps the most damning commentary on where America is headed, or already is, comes from Philips' 12-year-old entrepreneur son, who invented a temporary glue. It's chilling to watch footage of the kid on "Shark Tank" pitching his wares to venture capitalists as "for kids made by kids." Philips presents his product like a shady used car salesman or Professor Harold Hill from The Music Man, perfectly aping the sweaty, manic cadence of a showman. If the capitalist bug has gotten Philips early, so has economic melancholy. The filmmakers catch up with him years later, and his company is now a moderate success. A teenager and yet already a seasoned businessman, he tells them, "My definition of success is whenever you can just kind of chill, and not a lot of people can."

As Roderick debates leaving his life in Georgia behind for a new life in Asia, where he might be able to achieve this sense of chill, his partner Jon remains in limbo. With Roderick, he has a purpose; he has a community. The two write jingles together, and Jon listens eagerly as Roderick explains his creative process. Yet Roderick, who has a girlfriend in the Philippines, seems blithely unaware of what his departure would mean for someone like Jon, who has no exit strategy. For some, once the American Dream dies, there is no chance to look for it elsewhere.

Toward the end of "Carpet Cowboys," Mackenzie and Collier embrace the western setting the title evokes, filming the sun setting on a beach and over a graveyard. Some characters follow new dreams, while others wistfully remember the old days, haunted by "echoes of the past." The film's industrial-tinged synth score casts a tension between the humanist way MacKenzie and Collier have presented the stories of those who work in Dalton and the coldly efficient way they film the machines that create the product.

While the credits roll, a group of employees in a beige, cramped, fluorescent-lit room in one of the nameless companies endlessly walks in a circle over samples of carpets, testing their stress endurance. An earlier scene indicated these tests require 20,000 passes, which takes a human two weeks to complete. These tests will, of course, be repeated on new carpets in an endless loop of labor, just as those caught in the current economic web—artists and entry-level alike—are stuck in the never-ending cycle of Capitalist destruction of community and culture, left to bear the stress of it all in isolation and despair.

Now playing in limited theaters.