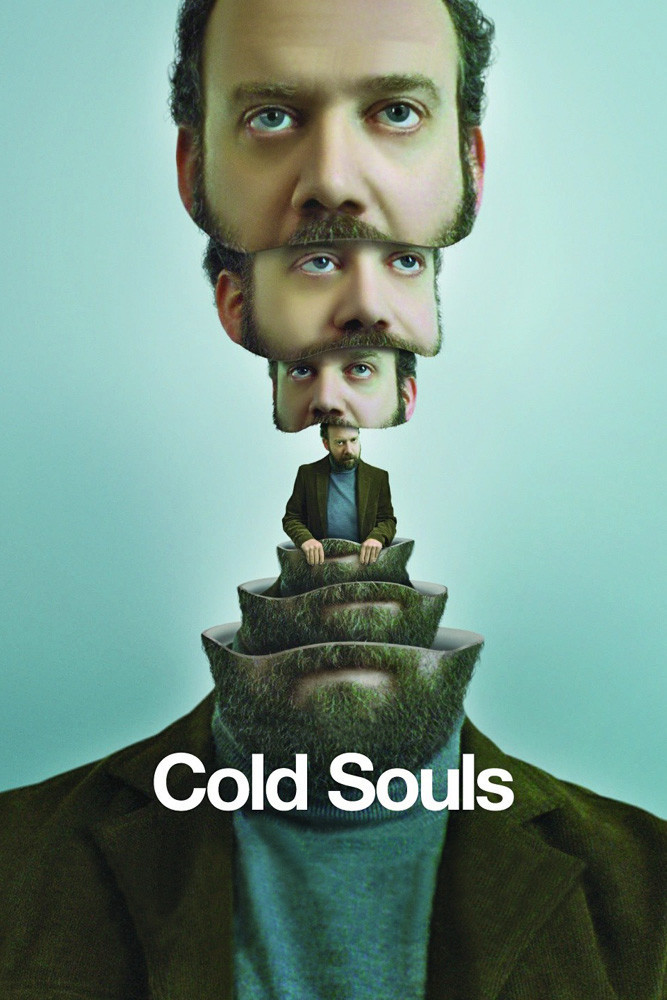

Would an actor sell his own soul for a great performance? No, but he might pawn it. Paul Giamatti is struggling through rehearsals for Chekhov's "Uncle Vanya" and finds the role is haunting every aspect of his life. His soul is weighed down, it tortures him, it makes his wife miserable. He sees an article in the New Yorker about a new trend: People are having their souls extracted for a time, to lighten the burden.

The man who performs this service is Dr. Flintstein, whose Soul Storage service will remove the soul (or 95 percent of it, anyway) and hold it in cold storage. As played by a droll David Strathairn, whose own soul seems in storage for this character, Flintstein makes his service sound perfectly routine. He's the type of medical professional who focuses on the procedure and not the patient. Giamatti, playing an actor named after himself, has some questions, as would we all, but he signs up.

"Cold Souls" is a demonstration of the principle that it is always wise to seek a second opinion. The movie is a first feature written and directed by Sophie Barthes, whose previous film was a short about a middle-aged condom tester who considers buying a box labeled "Happiness" at the drugstore. Clearly this is a filmmaker who would enjoy having dinner with Charlie Kaufman. Perhaps inspired by Kaufman's screenplay for "Being John Malkovich," she also credits Dead Souls, the novel by Gogol about a Russian landowner who buys up the souls of his serfs.

Gogol was writing satire, and so is Barthes. We hope that medical intervention can help us do what we cannot do on our own: Focus better, look younger, lose weight, cheer up, be smarter. If only it were as simple as taking a pill. Or, in Giamatti's case, lying on his back to be inserted into a machine looking uncannily like a pregnant MRI scanner.

His soul is successfully extracted and kept in an airtight canister. He's allowed to see it. It has the size and appearance of a chickpea. Lightened of the burden, he becomes a different actor: easygoing, confident, upbeat, energetic — and awful. Rehearsals are a disaster, and he returns to Flintstein, demanding his old soul back.

This is not easily done, for reasons involving Nina (Dina Korzun), a sexy Russian courier in the black market for souls. A Russian soul is made available to Giamatti, with alarming results. All of this is dealt with in the only way that will possibly work, which is to say, with very straight faces. The material could be approached as a madcap comedy, but it's funnier this way, as a neurotic, self-centered actor goes through even more anguish than Chekhov ordinarily calls for.

I suppose "Cold Souls" is technically science fiction. There's a subset involving a world just like the one we inhabit, with only one element changed. In an era of Frankenscience, "Cold Souls" objectifies all the new age emoting about the soul and inserts it into the medical-care system. Certainly if you have enough money to sidestep your insurance company, a great many cutting-edge treatments are available. And soul extraction is not such a stretch when you reflect that personality destruction, in the form of a pre-frontal lobotomy, was for many years medically respectable. Insert an ice pick just so, and your worries are over.

I enjoy movies like this, which play with the logical consequences of an idea. Barthes takes her notion and runs with it, and Giamatti and Strathairn follow fearlessly. The movie is rather evocative about the way we govern ourselves from the inside out. One of Nina's problems is that she has picked up little pieces from the souls of all other people she has carried. Don't we all?