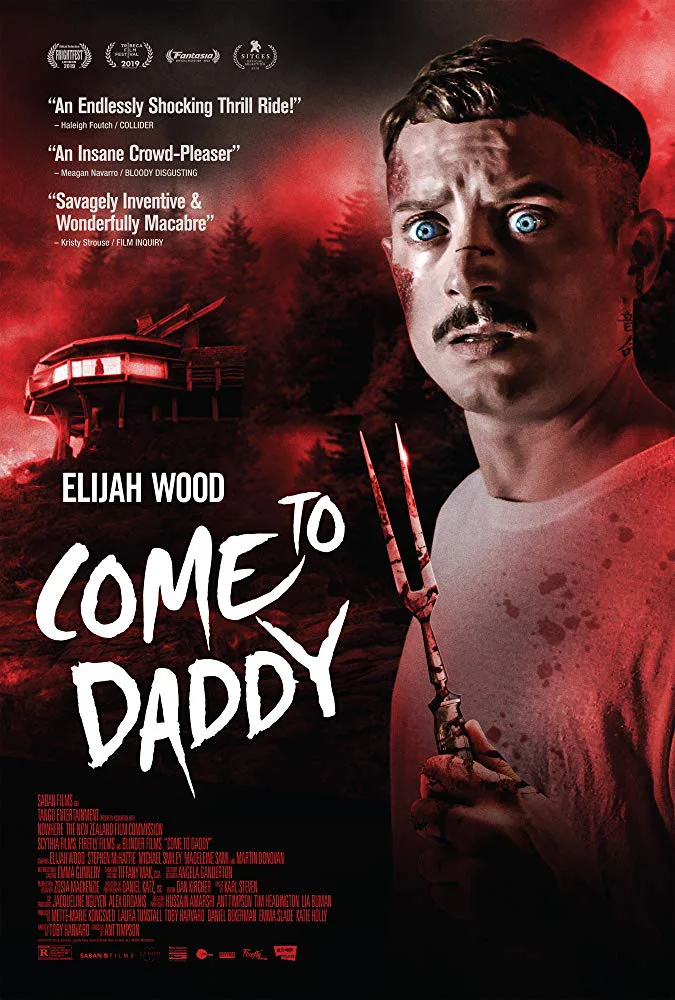

His father left when he was five years old. 30 years later, Norval Greenwood (Elijah Wood) receives a letter from his old man, hoping that the son will visit the father. That's the setup for "Come to Daddy," a film that keeps changing direction so often that it's almost a miracle the filmmakers don't give us tonal and narrative whiplash.

Instead, screenwriter Toby Harvard and director Ant Timpson (making his feature debut) have crafted a film that's as clever as it is strange. It's pretty strange, especially after the floor almost literally drops from beneath Norval, revealing how much of a lie his current situation is and, indeed, his entire life has been.

Before that moment, though, we follow Norval as he arrives at a remote location via bus, walks through the woods, and finds his absentee father's beach-side home. His father drew him a map so that Norval could find his way. This isn't just a man who has left his family behind. He seems determined to leave the entire world behind.

After some hesitation, Norval knocks on the door. After a long pause, Gordon (Stephen McHattie) answers it. There's the quick introduction, which seems odd under the circumstances, although we—and Norval, for that matter—easily can dismiss that on account of the three-decade separation. Norval doesn't remember what his father looked like, and the father surely won't recognize his son, especially if his sudden departure and choice of home are any indication of how well Gordon has kept up with his family in the intervening decades. The two men hug—a good start and, well, the only good moment between these two characters for the rest of the story.

Over the next couple of days, the two men never connect. Norval tells his story, how he has had problems with alcohol dependence, almost committed suicide, and currently lives with his mother in her fancy Beverly Hills home. Things seems to be working out now, though. He has stopped drinking, and he's something of a big deal in the music industry. He even has a gold cellphone designed by a famous singer—one of only 20 in the whole world.

Gordon, meanwhile, hears about his son's alcohol problem, and he responds by making a show of a long pour from a wine bottle at dinner—moaning in delight as he takes a big sip from his glass. He makes a big game out of calling Norval's bluff when the son says he knows Elton John. Gordon doesn't just have to call out his son's lies. He has to embarrass his own kid to make some kind of point. As for that cellphone, it ends up in the water, and Gordon jokes that, now, there are only 19 of them in the whole world.

Some other weird things happen, too. Gordon is often on the phone at night, whispering about some kind of deal with an unknown caller. When father and son agree to go for a swim, Gordon stays behind, and while floating in the ocean, Norval is startled by a rock that comes quite close to hitting his head. The son chalks up all of this to the fact that Gordon is an alcoholic, who was probably drunk when he wrote the letter and now resents the presence of a son with whom he wants nothing to do. Even then, though, something is seriously off about this reunion.

The verbal conflicts suddenly turn physical in one key moment, and at this point in describing the characters and the plot, there is really nothing to do but to stop. Describing more would be unfair, because Harvard has almost nothing but surprises left in his narrative arsenal.

Here's what can be said: The film takes this father-son dynamic to increasing extremes, and the rest of the plot mirrors that snowball-down-a-hill effect. The house has a couple of secrets to discover, including some hidden mementos that at first suggest the father whom Norval meets was a very different man at some point in the long-ago or very recent past, as well as a hatch in the floor in the middle of the living room. Norval's visit becomes even less amiable, which would have seemed impossible given Gordon's descent from passive-aggressive resentment to flat-out homicidal rage. The sudden appearance of a group of goons from not-so-dear, old dad's past, though, can force that kind of re-evaluation on how bad a situation can become.

The vital thing is that Harvard's screenplay never cheats. There's a twisted sense of logic to everything that unfolds (and sometimes, such as Norval's extra-effort but unnecessary attempts to free someone bound in chains, a warped humor within that twisted logic). There are fights (including one that showcases how tough the cardboard rolls holding plastic wrap really are) and plenty of instances of sneaking around, outside the house and at a nearby motel, where Norval has to maneuver quietly past some people sleeping peacefully after an orgy. Timpson stages each of these scenes with straightforward efficiency. He's smart enough to know both that the humor comes from the assorted scenarios, without any extraneous directorial playfulness, and that there's still tension to be mined in even the most absurd situations.

The mixture of demented humor and thrills works in "Come to Daddy"—not only because each complication logically follows from a previously defined complication or scenario, but also because there is sincere pain, longing, and desperation at the heart of Norval's situation. He just wants to know why, and the universe chuckles at thinking something so complicated could be that simple.