The interior dimensions of the German U-boat in "Das Boot'' are 10 feet by 150 feet. The officers' mess is so cramped that when a crew member wants to move from the front to the back, he asks "permission to pass,'' and an officer stands up to let him squeeze by. War is hell. Being trapped in a disabled submarine is worse.

"Das Boot'' is not about claustrophobia, however, because the crew members have come to terms with that. It is about the desperate, dangerous and exacting job of manning a submarine. In a way we can focus on that better because it is a German submarine. If it were an American sub, we would assume the film ends in victory, identify with the crew, and cheer them on. By making it a German boat, the filmmakers neatly remove the patriotic element and increase the suspense. We identify not with the mission, but with the job.

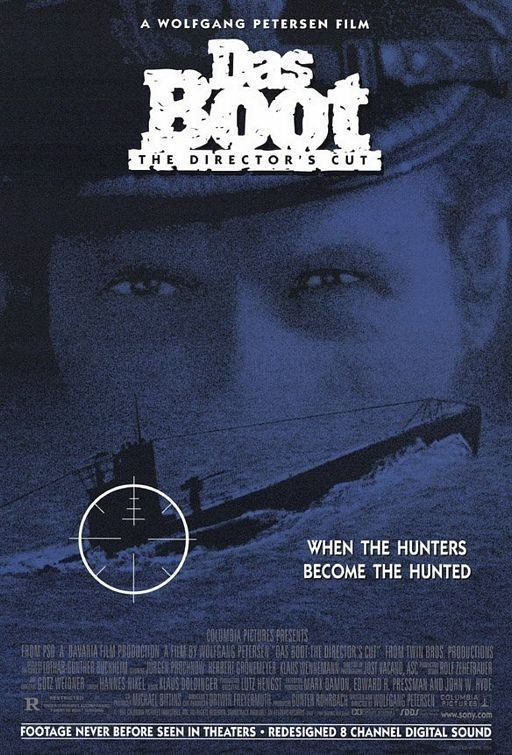

When "Das Boot'' was first released in the United States, it ran 145 minutes and won huge audiences and no less than six Oscar nominations--unheard of for a foreign film. This 1997 release of Wolfgang Petersen's director's cut, is not a minor readjustment but a substantially longer film, running 210 minutes.

The film is like a documentary in its impact. Although we become familiar with several of the characters, it is not their story, really, but the story of a single U-boat mission, from beginning to end. There is a brief opening sequence in which the boat puts out to sea from a French base, and a refueling sequence near the end, but all the other scenes are shot inside the cramped sub, or on the bridge.

And it's not shot in tidy setups, either; the cinematographer, Jost Vacano, hurtles his camera through the boat from one end to the other, plunging through cramped openings, hurdling obstacles on the deck, ducking under hammocks and swinging light fixtures. There are long sequences here--especially when the boat is sinking out of control--when we feel trapped in the same time and space as the desperate crew.

The boat's captain (Jurgen Prochnow) is the rock the others depend on. Experienced, steady, he's capable of shouting "I demand proper reports!'' even as the boat seems to be breaking up. He is not a Nazi, and the movie makes that clear in an early scene where he ridicules Goering and other leaders for their "brilliant strategy.'' For this mission (an assignment to torpedo Allied shipping in the North Atlantic), a journalist has been assigned to join the crew. Played by Herbert Groenemeyer, he probably represents Lothar-Gunther Buchheim, whose novel was based on these wartime events. The addition of this character is useful, because it gives the captain a reason to explain things that might otherwise go unsaid.

The centerpiece of the film is an attack on an Allied convoy; the U-boat torpedoes three ships. We share the experience of the hunt; they drift below the surface, waiting for the explosions that signal hits. And then they endure a long and thorough counterattack, during which destroyers criss-cross the area, dropping depth charges. The chase is conducted by sound, the crew whispering beneath the deadly hunters above.

Then comes the episode that was endlessly discussed when the film came out in 1981. Having finally outlasted the destroyers, the sub surfaces to administer a coup de grace--a final torpedo to a burning tanker. As the ship explodes, the captain is startled to see men leaping from its deck: "What are they doing still on board?'' he shouts. "Why haven't they been rescued?'' Drowning sailors can clearly be seen in the flames from the tanker. They swim toward the U-boat, their pitiful cries for help carrying clearly across the water. The captain orders his boat to reverse at half speed, to keep it away from them. What does he think of having let the victims drown? He does not say. Only one sentence in the ship's log ("assumed no men were on board'') gives a hint. It is against the instinct of every sailor to let another sailor drown in the sea. But in war, it is certainly not practical for a submarine to take prisoners. Somehow it is easier when the targets are seen through periscope sights, and the cries of victims cannot be heard.

That scene supplies another example of why it is effective that "Das Boot'' is a German sub. One cannot easily imagine a Hollywood film in which American submariners are shown allowing drowning men to die. The German filmmakers regard their subject dispassionately; it is a record of the way things were.

Wolfgang Petersen's direction is an exercise in pure craftsmanship. The film is constructed mostly out of closeups and cramped two- and three-shots. All of the light sources are made to seem visible (when the lights fail, flashlight beams dance in the darkness). Long, involved shots are constructed with meticulous detail; when a sailor races toward the torpedo room, the reactions from the other men seem exactly right.

The sound adds another dimension. During the destroyer attacks, the boat rocks with explosions and reverberates with desperate cries and commands. During the cat-and-mouse chases, we can hear the sonar pings bouncing off the U-boat's hull. When the boat dives below its rated depth, rivets come loose like rifle bullets. When it appears the boat may be trapped at the bottom of the Straits of Gibraltar, the sailors lie on their hammocks, gasping oxygen like dying men.

Francois Truffaut said it is impossible to make an anti-war film, because films tend to make war look exciting. In general, Truffaut was right. But his theory doesn't extend to "Das Boot.''