It's easy to view cinema as a mere escape from reality, a temporary break from our everyday problems. In times of great distress and division, people may dismiss films as unimportant distractions. Yet consider what happened to a Palestinian fighter named Sulaiman Khatib. While serving time in prison, he watched "Schindler's List" and suddenly felt overcome with emotion. The characters being slaughtered onscreen were the ancestors of the very same people Khatib had sworn to oppose with every fiber of his being. He had even stabbed an Israeli man, and was so shocked by his own capacity for violence that he felt as if he were watching himself in a play. Now for the first time in his life, Khatib found himself empathizing with his enemies by watching the portrayal of their suffering on film. That is the profound impact cinema can have on one's worldview.

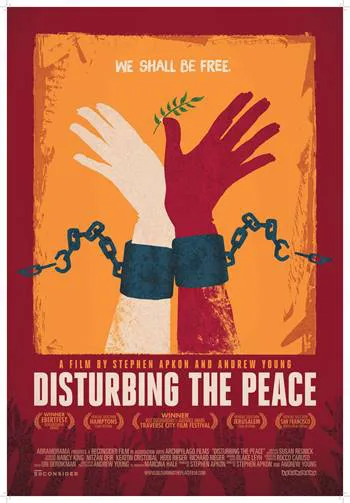

Khatib is one of the primary subjects in Stephen Apkon and Andrew Young's documentary, "Disturbing the Peace," which effectively illustrates the universality of suffering by juxtaposing the stories of people on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It doesn't take long for their memories of bloodshed and devastation to blur together, along with the footage of corpses strewn amidst endless rubble. It's ironic to hear the Israeli subjects recount how the establishment of a Jewish state was meant to provide them with security, since it quickly proved to offer anything but. With acts of terror being carried out by both sides of the conflict, the acquiring of fresh rage and bloodlust has become a rite of passage for generation upon generation. "Our world was a cemetery of the living," replies Shifa al-Qudsi, a Palestinian mother who became so enraged by the heartlessness of the Occupiers that she decided to sacrifice her life as a suicide bomber. Anyone living on Chicago's South or West sides could relate to this woman's horror of watching one kid after another get killed while walking home from school.

Al-Qudsi chokes up while remembering how she had to explain to her child that she wouldn't be coming home. Instead, she wound up alive and in prison, where she had her own small yet life-altering epiphany. After learning that the Israeli brother of a female guard was killed, she had a conversation with the woman that subverted her own beliefs about "the enemy." When the guard told her, "I am against any kind of violence," Al-Qudsi discovered that there were indeed Israelis who desired peace. One of them, Chen Alon, was a soldier who no longer wanted to be part of an army that was used as a "mechanism of oppression." The fiery criticism faced by him and his fellow peaceful protestors stands as proof that there are multitudes of Israelis and Palestinians unwilling to acknowledge that they are equally at fault. The somber footage of a recent failed stalemate—which led John Kerry to ultimately throw up his hands and leave—accentuates the fact that leaders cannot be counted on in order to bring about real change. It must come from the people, and as the film reaches its second act, its subjects have come together to form a movement, Combatants for Peace, which was officially established in 2006.

"Disturbing the Peace" is a courageous and uplifting film that deservedly earned a rapturous ovation when it screened at Ebertfest this year, in part because two of its subjects, Khatib and Alon, were in attendance. If it lacks a certain urgency in its first two thirds, that is because the events that it covers are recounted through staged flashbacks mixed with archival footage. There are times in which the low voices combined with the melancholy score can cause the mind to wander at the precise moments when one's attention is most needed. The subject matter itself is so compelling that it practically guarantees that the film will never be dull, though regardless of its material, a documentary is only as good as its editing. In this case, editor Ori Derdikman does a remarkable job of maintaining a brisk pace without ever diminishing the vividly textured humanity observed by Young's lens. Though he and Apkon do a fine job of laying out the history of the movement, the film really comes to life in its last third as we're finally enabled to experience events in real time.

The most riveting scene in the picture centers on an argument between a Palestinian man, Jamil Qassas, and his wife, Fatima. He wants to take their two young daughters to a peaceful demonstration, and she initially refuses by saying that they should be careful not to impose their own views on their children. Yet she quickly changes her tune by defending her choice to take them to violent demonstrations, since they are more reflective of their everyday reality. She feels her husband is betraying their family by collaborating with Israelis, and voices assumptions about them that would likely have been demolished had she chosen to actually meet them. This leads to a wonderful sequence in which the Combatants for Peace stage a demonstration at the Israeli West Bank wall, which is in itself an apt metaphor for the limitations of an ideology. Chanting "Two states for two peoples!", the marchers hold up their own wall that breaks apart, revealing an enormous, meticulously designed face with outstretched hands. When Israeli soldiers disrupt the demonstration with sudden violence, Alon glances at them from behind a fence and realizes that his former comrades are the real prisoners—forced by their leaders to perpetuate cyclical misery with no endgame in sight.