In the two recent films that gave him an international name, Canadian director Denis Villeneuve brought an acutely concentrated vision to bear on stories of violent conflict beyond his native land. The Oscar-nominated "Incendies" concerned the horrors of war in a nameless but vividly evoked Middle Eastern country, while last year's "Prisoners" was a lacerating tale of kidnapping, terror and torture in a no less carefully described Pennsylvania town.

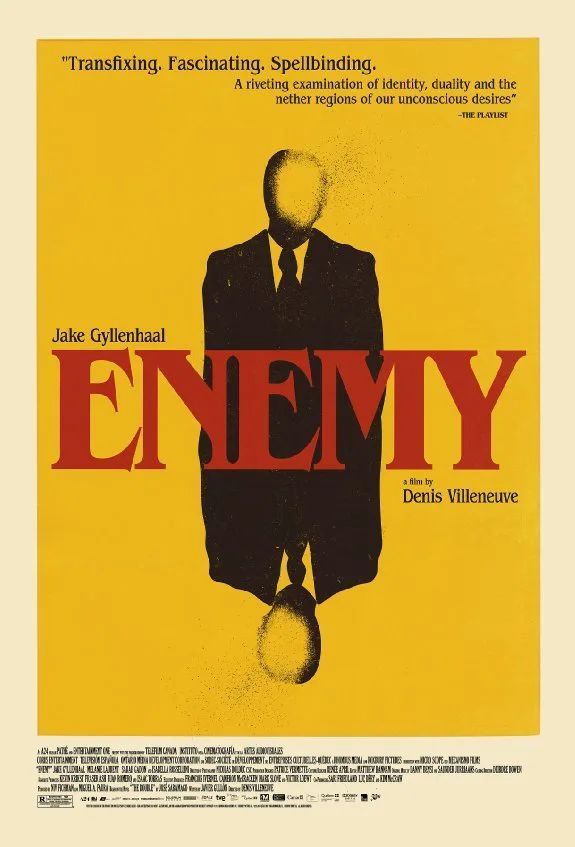

"Enemy," Villeneuve's latest (it was filmed between the two above-mentioned films, though it is being released after the latter), differs from the earlier works not only in being set in Canada, but also in offering a story that's ostensibly less concerned with painful real-life struggles than with dream-like subjective perplexities. Adapted by screenwriter Javier Gullon from Portuguese author Jose Saramago's novel "The Double," the brooding, crepuscular drama features Jake Gyllenhaal (who also starred in "Prisoners") in the roles of a man and his double.

Since stories of doubles, with their long pedigree in literature and cinema, inherently belong to the realm of the fantastical, "Enemy" obviously stands apart from the traumatic real-world political and criminal traumas of its two predecessors. Less ambitious (and, at 90 minutes, far shorter) than those films, it's inevitably less impressive, more like a semi-whimsical short story by a master whose real forte is challenging realistic novels of epic scope.

Yet that's not to suggest the three films are entirely different. Also tinged with the quality of nightmares, the violence in "Incendies" and "Prisoners" was, or had the feeling of being, fratricidal or internecine. In "Enemy" there's also a sense of the antagonists being closely related, whether as long separated twins, as two aspects of the same personality, or as guys who fall into a violent competition due to the accidental "kinship" of their identical looks. Which of these possibilities, if any, comprises the "real" explanation is a question the film keeps thrusting back to the viewer.

The movie's look has the color of nicotine stains, or a smoggy freeway at dusk. Adam Bell (Gyllenhaal) has brown hair, a brown beard and inveterately wears rumpled brown or tan clothes. He lives in a vast brown city called Toronto and teaches history in an institutionally light-brownish classroom that's only half-full of students. In one of the few lecture snippets we hear from him, he tells his class that the rulers of Rome gave its citizens bread and circuses for purposes of distraction. With the blank affect of a man who's bored with every aspect of his life, Adam himself seems in need of distraction. Which is perhaps why, one day in the faculty room, he takes another teacher's advice to seek out a certain movie on DVD, one that promises to lift his spirits.

Watching the film later, Adam notices something strange in the background of one scene: an actor playing a bellhop has his own face. Startled, he does some research and discovers that the actor, Anthony Claire, has only three films to his credit. After finding out where the man lives, Adam begins calling his home, and initially gets only hostile, suspicious reactions from Anthony and his pregnant wife, Helen (Sarah Gadon).

Before they ever meet, we see that Adam and Anthony are leading roughly parallel lives. Neither seems professionally fulfilled. They are underachievers facing the approach of middle age with a glum dissatisfaction that perhaps masks an underlying anger, a desire to lash at the world—or someone else. Both men are also involved with blonde women who resemble each other both physically and in their difficulties with their partners. While the angry sex and icy silences shared by Adam and his girlfriend Mary (Melanie Laurent) signal a relationship about to implode, Helen evidently agonizes over bearing the child of a man she suspects of infidelity.

Once the two men encounter each other and, via the magic of special effects, inhabit the same visual space, the movie's most salient virtue comes into focus: Gyllenhaal, a very talented actor in most circumstances, here does exceptional work playing two men who are almost—but not quite—identical. The differences are small, and more emotional than physical. Anthony is meaner and more imperious, Adam more resentful and recessive. Observing these subtle contrasts offers no end of fascinations, yet we're simultaneously aware of the inevitabilities implied by the characters' competitiveness and hostility: each will try to bed the other's woman, and only one will be left alive at the end.

As noted, Villeneuve and Gullon leave the meaning of all this an open question—or perhaps several questions at once. Is the French Canadian director's tale of Anglo Canada an allegory of his culturally divided homeland? Is the cryptic story a symbolic meditation on something central to cinema, the fraught relationship between an actor and the "double" he fashions in creating a character who bears his likeness? Does it contain a whiff of Villeneuve's feelings about Canada's greatest art-film auteur prior to his arrival, David Cronenberg, whose "Dead Ringers" is one of cinema's finest tales of doubles.

Take your pick, or better yet, supply your own reading. What seems certain is that Villeneuve is a very self-conscious artist whose estimable work descends from the European high-modernist tradition of decades past. Thus, in "Enemy," we don't find a clear debt to any particular doubles-themed work of literature or cinema, but rather echoes of the concerns and stylistic penchants of directors such as Bergman, Bunuel, Polanski, Kieslowki and Antonioni (especially in the contemplation of Toronto's sprawling architectural jumble). All of those filmmakers came from an indigenous national cinema, then went on to become transnational cosmopolitan artists. The same is now happening to Villeneuve. Perhaps questions of identity and "doubleness" go with making that kind of leap.