The greatness of Quentin Tarantino movies is that I can watch any of them multiple times and still not be able to tell you if I like them. I long for more viewings to unlock their secrets; if you ask for endorsements, I'll tell you they are "very rich" in ideas and details. "Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood" is no different. It raised for me a number of questions.

How much do we rely on serendipity?

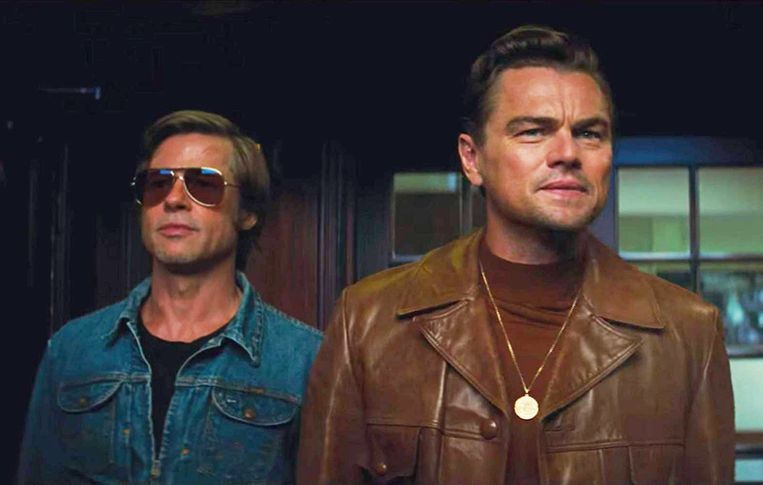

"OUATIH" features four main characters as echoes of each other. Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) is the star that Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) should have been. Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) is the rising star that Pussycat (Margaret Qualley) could have been. Dalton fades as Tate grows. Booth and Pussycat explicitly, and all four implicitly, dedicate their lives to the service of narcissists.

Is it a rumor that killed Booth's career? What did Dalton—an emotional mess— bring to Hollywood that is unique among all the others gunning for the same status? Why did Tate become the star, while Pussycat—with mesmerizing blue eyes, who dances and romps as much as Tate—became the moldy hippie?

The actors playing them, especially DiCaprio, Pitt, and now Robbie, have persisted in their careers on screen perhaps because of reputations that are (mostly) scandal-free. But, even with their work ethic and clean records they have been competing with a flock of aspirants that had and gave everything they did. Why do we know their names and faces, and not others?

So, is destiny, a sequence of serendipities? Patrick Montgomery's documentary "The Complete Beatles" (1982) suggests that the Fab Four kept rising because of a decade of lucky breaks, after which they fell apart. Nearly all my great personal, professional, and spiritual accomplishments—from fatherhood to epiphanies on life—can be traced back to chance encounters. This idea of the random luck of life feels embedded in Tarantino's semi-fictional narrative.

Are rumors that powerful?

Why is Dalton, not Booth, the star? Cliff Booth has the charisma, gravitas, and smile of a leading man, but is a pariah who brings a bad "vibe" to a Hollywood set. He should be headlining your favorite action picture but is instead an unknown gofer and occasional stuntman for the fading Rick Dalton. His chiseled torso is now tanned leather as he sits on a hot Los Angeles roof reflecting on life while repairing a television antenna.

Perhaps it is because of the rumor that Booth killed his wife. The courts did not convict him, yet public opinion—at least in the industry—has ostracized him. One scene allows us to infer that a drunken Booth killed his complaining wife while sailing. He does not get upset in that scene, though for a moment in another scene he threatens his dog for whining. We do not find photos of Booth and his wife in his home, though we find enough—well-organized—dog food to feed a cavalry of canines. His ferocity in two scenes against members of the Manson family is so violent—though perhaps justified—that I cringed. On the flip side, he is compassionate toward a dying old man, fiercely loyal to his boss, and seems at peace with life's vicissitudes. The film gives us leads to investigate the wife's story, but they are all herrings as red as his wife's hair.

Dalton lacks Booth's good looks. He lacks Booth's casual equanimity. He cares only about himself, while Booth goes out of his way—risking his own safety—to make sure some hippies are not exploiting an old acquaintance, George Spahn (Bruce Dern). Dalton works from a trailer larger than the home Booth lives in. Dalton's face is on the television screen in your home, while Booth's home sits behind a giant drive-in screen.

But, if someone was found not guilty, do we trust them? In class, I ask undergrads—who are younger than the murder and the trial—if O.J. Simpson murdered his wife (and they do not know about Ron Goldman). Almost all the hands rise. When I ask how many watched the trial, the best I get is "I watched the miniseries."

Can I beat Bruce Lee?

As the film's clock moves us closer to that night in August 1969, the movie explores the rise, decline, and fall of cultural legends. Rick Dalton, once a leading man, is now the withering heavy, grasping for television roles propping up other new stars. Sharon Tate is a young beautiful blonde in the first phase of a long Hollywood career. We meet the film's only mature performer, the energetic eight-year-old Trudi (Julia Butters) who has just entered the Hollywood machine. We also meet the exhausted codger George Spahn: Hollywood has forgotten him, while he has—save for a few nightly television shows—forgotten Hollywood.

And in the middle, we find Bruce Lee, a fighter surpassed in legend only by Muhammad Ali. Someone asks him: can you beat Cassius Clay?

Calling him "Cassius Clay" is mockery as much as Booth calling Lee, "Kato" and a "dancer" (as opposed to a "warrior"). Muhammad Ali's legend in American eyes does not skyrocket until he (a) regains the title a few times in the 1970s and (b) he lights the torch at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. At this point in the film's 1969, the former Heavyweight Champion of the World was already "Muhammad Ali," had already lost his title because of his refusal to enter the military draft, and had not yet returned to boxing.

Cliff Booth (in his 50s) fights Bruce Lee (not yet 30) to a draw. More than that, he whips Lee into a car. In that moment, I had flashbacks to the shock of discovering that the numerous martial artists hired by the Shaw Brothers for their hundreds of action epics were dancers and gymnasts. Is Bruce Lee, the author of a cinematic work of scripture, "Enter the Dragon," also ... a dancer? In a fight or, for that matter, a dance-off, I would lose to almost every dancer I know. Still, is the invincible Bruce Lee ... "vincible"? Is Bruce Lee, the philosopher of Jeet Kune Do, like the rest of us? Would his star be as untouchable if he (and his son Brandon) did not die so early? This last question illustrates the absurdity of my premise: I am comparing a flesh-and-blood human's mortality with the mythology we impose upon him.

The film's iconoclasm takes other directions. We visit Cliff Booth's monkish quarters. James Stacy (Timothy Olyphant)—one of the rising stars that Dalton's role supports—leaves his cowboy hat, six-shooter, and boots, for a canvas jacket and motorcycle. Contrasting the "dumb blonde" she plays in the movies, dancing to every tune, Tate enjoys complex literature (like Tess of the d'Urbervilles). Despite her cover girl porcelain whiteness, her feet are dirty, she snores at night, and feels pangs of pain and melancholia in pregnancy ... like a normal person.

On that note, in this film taking its twists and turns with the modern #MeToo movement, we have Roman Polanski (Rafal Zawierucha) and Charles Manson (Damon Herriman). One a filmmaker, whom we celebrate with standing ovations, who was arrested for sexual assault, and still lives a life on the run from the law, outside our borders. The other is a singer, a convicted murderer whose star continued to rise in our popular culture even after legislators passed laws against him. Further, Wikipedia tells me that television star James Stacy was arrested multiple times in the 1990s for misconduct with young girls.

The mythology that accompanies legends is louder than fact.

What is America?

Like today's armchair MAGA warriors, "OUATIH" longs for an America that no longer exists, if it ever did in any place, outside our imaginations. Sirhan Sirhan, killer of Robert F. Kennedy, gets a blip of attention, nothing compared to the numerous shows and songs broadcasting fictional killings. Bruce Lee remains one of America's great icons, and one of our few enduring East Asian icons. Aside from the mention of Cassius Clay, there is one African American in the film, an extra in one of the Westerns. All the Latinos in the film are swarthy background-dressing for the White stars on and off-camera. It was a white nation, or was it?

The sentiment of Italy as a special 1960s off-white wonderland hovers throughout the film, in an era of go-go boots succeeding the neorealisms of De Sica and Rossellini. Italy enchanted American audiences until the Godfathers and Goodfellas controlling mean streets shifted the conversation in the next decades.

Tarantino brings Italy into its main characters. We meet Tate as she dances like Eckberg, Cardinale, or Loren, from Fellini's circuses, but in the Playboy mansion. She has the dual, twin love interests (Polanski and Sebring) we find in Bertolucci's movies for the next 40 years. Dalton himself is Visconti's declining Prince of Salina, from "The Leopard" (1963). In the film's latter scenes, Dalton is surrounded by the wardrobe of Antonioni's "Blow-up" (1966) on Booth (black belt, white pants, black shoes) and Dalton's wife Francesca Capucci (Lorenza Izzo, dressed in a full-length net of red yarn). Booth driving in blue beat-up convertible across LA recalls Thomas (David Hemmings) driving his Rolls convertible across London in "Blow-up."

What is real?

A jarring aspect of "Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood," is the play between fantasy and reality. Sometimes they look like flashbacks. Sometimes, they are real or fake flashbacks within real or fake flashbacks. Dalton tells Stacy about a role he did not get in "The Great Escape," yet we watch clips of scenes featuring Dalton—not Steve McQueen—in the movie. While we assume those scenes are in someone's imagination—perhaps both Dalton and Stacy or Tarantino himself—we do not know if the dialogue is commentary or relevant for that moment in "Once." Likewise, in a cut, Stacy's hat covers his face without prompt.

What is happening? Everything mixes together, in the same way that we often remember particular movie scenes better than particular moments in our lives.

Likewise, are any of the relationships in the movie substantive, real relationships? In an opening scene, we learn Dalton (in tears looking for a shoulder to cry on) is Booth's employer, not his friend. Jay Sebring, whose relationship with Tate is a big question of its own, speaks of getting paid $1,000 a day to maintain someone's hair. It seems that all the relationships are either professional and/or opportunist.

The film's climax does two things. The obvious is that it changes history to something too violent for most of us, yet not as violent as reality, resolving into something hopeful and happy: Dalton befriends Booth and meets the not-murdered Sebring and Tate.

"Once" reminds me of the shift we witnessed in Clint Eastwood's depictions in the early 1990s, with "Unforgiven" (1992) and "A Perfect World" (1993) that seemed to signal a change in his depictions of movie violence, from something playfully evil to something somber. The violence of "Once" seems the most compacted yet in those small bursts, the most explicit. Meaning, "Reservoir Dogs" has the ear-cutting, but we do not see the slice. "Pulp Fiction" has the various shootings, but the camera shots hold on the shooters not the victim, even when brain-bits splatter everywhere. There's a melancholy about the victims here that has not been seen in Tarantino's work before.

And despite multiple views, I know I will keep thinking about "Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood." I still won't be able to answer if I like it.