When I was in college in Houston, I wrote a piece about film criticism. And while I was at the local library looking for books to research, I discovered The Resistance: Ten Years of Pop Culture That Shook the World by Armond White. Full of polarizing pieces where an African-American film critic went after Hollywood for the various ways it has disparaged and degraded African-American culture, I was obsessed with this book. I checked it out several times.

During that time, I had a correspondence with James Wolcott, the witty New York-based critic/columnist over at Vanity Fair. I asked him once if he ever saw a copy of The City Sun (the Brooklyn weekly where White was the arts editor/film critic) out and about, could he please pass it over to me?

In October of 1997, I got a package from Wolcott where he enclosed reviews by White not from The City Sun, but from New York Press. (The City Sun ceased publication a year before.) It turned out White began writing reviews for this alt-weekly, along with two other critics: Godfrey Cheshire and Matt Zoller Seitz. I never heard of Cheshire, but being from Houston, I was aware of Seitz's reviews, which he would write over at the Dallas Observer and get reprinted at the Houston Press.

For a couple years after that, Wolcott sent me reviews where White would be on one side of the page and Seitz or Cheshire would be on the other side. By the time the New York Press finally hit the Web in 1999, I could get all three of them on a weekly basis.

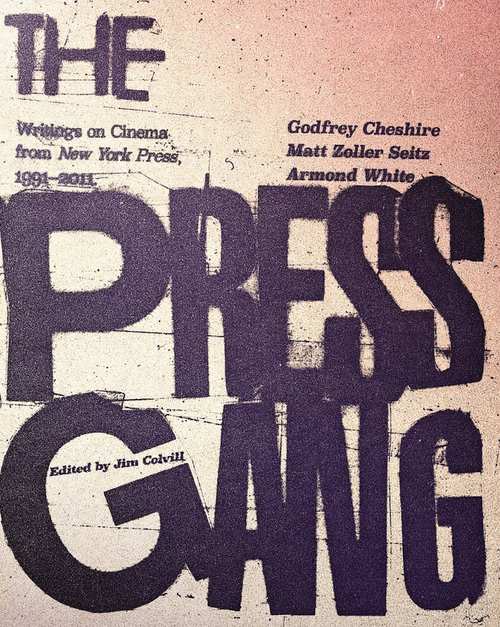

In August of this year, Seven Stories Press released The Press Gang: Writings on Cinema from New York Press, 1991-2011, a book which chronicles a lot of the reviews these three men did at this publication, which shut down in 2011. Edited by Jim Colvill with an introduction by Jim Knipfel, Gang rounds up the many noteworthy pieces written by Cheshire, Seitz and White. It's an amazing compilation of pieces from critics who (still) have a lot to say about film. (Once upon a time, I joked on Twitter that these guys should get together and write a memoir called "Oh Shit, Here They Come!")

But how do these critics feel about how their past reviews compiled in one book? I spent one Friday afternoon interviewing them individually about the book and their memories:

Godfrey Cheshire just turned 40 when he moved to New York in August of 1991. After a dozen years as the film critic for the North Carolina-based Spectator Magazine, Cheshire headed to the Big Apple to be a top-tier, New York critic.

At the behest of friends, he sent some clips to the Press, which didn't have a film critic. "I was familiar with New York Press through visiting New York in previous times," says the Raleigh-born, New York-based Cheshire, now 69, "and I liked it too." In less than a month, Cheshire was called over to the Press offices, where publisher Russ Smith and editor John Strausbaugh hired him as the resident film reviewer. "It was pretty quick," he says. (The first piece he wrote—a double review of "My Own Private Idaho" and "The Rapture," which he saw at that year's New York Film Festival—is the piece that starts off Gang.)

For five years, Cheshire was the lone critic, writing reviews that would also be reprinted back home at the Spectator. (Occasionally, some contributors were brought on to do second-string Press reviews, including veteran Village Voice critic Michael Atkinson). It was during this time that Cheshire would fall in love with an area of foreign-filmmaking that he would eventually become a renowned expert on: Iranian cinema.

This actually began when he started attending NYFF in the ‘80s and getting into cinema from another part of the world. "In the late ‘80s," he remembers, "I started getting interested in the Chinese films they were showing, like Zhang Yimou's first film ‘Red Sorghum' was shown there. I saw Hou Hsiao-hsien's ‘A Time to Live, A Time to Die.' And when I got to New York in ‘91, I was continuing to be interested in Chinese cinema."

His pieces on Chinese films caught the eye of the editors of Film Comment, who sent him to Beijing to cover the making of Chen Kaige's "Farewell My Concubine." The magazine also got him to cover an Iranian-film retrospective at Lincoln Center, where he got into the films of the late Abbas Kiarostami, a filmmaker who would become a close friend. He says, "I think because I didn't see just one or two films—I saw a bunch of films and I was really kind of knocked out by the whole thing—that I became very avid about seeing more and writing more about that." Along with writing extensively about Iranian cinema for the Press, he would also be one of the first critics to lament the oh-so-impending death of film print, which he did in such pieces as the mammoth "The Death of Film/The Decay of Cinema" and "Film Going Digital," both of which appear in the book.

The relationship between Cheshire and the Press came to an abrupt end at the close of 2000. While it was rumored a printed takedown of New Yorker critic Anthony Lane led to his downfall, Cheshire believes it had more to do with economics. (Translation: they just couldn't afford him anymore.) After that, he continued to do criticism when he wasn't heading back to Raleigh to make his first film, the 2007 documentary "Moving Midway."

These days, you can find Cheshire's work in such spots as The New York Times and, yes, RogerEbert.com. (One of these days, he will finally drop that magnum opus on Iranian cinema he's been working on for so long.) And while he doesn't dwell too much on his time at the Press, Gang did bring back a lot of memories for him. "Because I think that this book captures something very special both in terms of film history and in terms of the history of film criticism. Because the decade itself for cinema was a very, very rich one—and, I think, maybe the last that was so rich in the ways that it was."

Cheshire says that the Press editors were looking for another critic—a "Joe six-pack," he says—to counter the highbrow criticism Cheshire was usually dropping. And this is where Matt Zoller Seitz enters the picture.

Seitz was a film critic whose pieces in the Dallas Observer led to him being a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism back in 1994. If you ask Seitz, he was seen more as a highfalutin critic to readers back in Texas. "In Dallas," remembers Seitz, "I was known as this kind of pointy-headed intellectual, compared to the other people who were writing about film regularly there. I definitely wanted to be the, you know, J. Hoberman of Dallas. It was sort of my goal."

After the Pulitzer love, Seitz sent his clips to New York papers, including the Press, who was looking for another critic at the time. He eventually joined the staff in 1995. He was already living on the East Coast, serving as the New Jersey-based Star-Ledger's pop culture critic, eventually becoming the paper's TV critic, along with Alan Sepinwall. "It had been a lifelong dream of mine to be a film critic for a New York publication," he says, "and the circumstances were perfectly aligned."

By the time White started writing in 1997, the film section became a part of the paper where three, very opinionated men laid out all they had to say about movies that week—albeit a section where Seitz considered himself the Ringo of the crew. "I think I probably had less of an ego than the other two," he says, "because I was comparatively young."

Seitz felt it was his duty to devote column space to the movies, filmmakers and festivals that weren't getting a lot of publicity at the time. "I got to write, like, anywhere from 1500 to 3000 words about things like the New York Underground Film Festival," he remembers. "I would deliberately leave, you know, the actual New York Film Festival to Godfrey or Armond a lot of the time because I thought it was more important to write about the little festivals around town that weren't getting any press. And so, that was, to me, my editorial counterweight to Godfrey and Armond."

Out of the three of them, Seitz has had the most going on in his personal life. His first wife, Jennifer Dawson, died of a heart attack in 2006, prompting Seitz to walk away from doing reviews at the Press. (His last review, an emotional, emphatic rave of "Superman Returns," is also in the book.) He would go to be the TV critic at New York Magazine and its online counterpart Vulture, as well as become the editor-at-large for this very website. He has gone on to write books on both filmmakers and TV shows.

He would later marry his wife's sister, Nancy, in 2017, and move to Cincinnati a year later. Unfortunately, Nancy died of cancer earlier this year. These days, he's been helping his father, jazz pianist Dave Zoller (who was diagnosed with stage 4 esophageal cancer in March), produce an album full of covers from Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, as well as work on a documentary that covers his father's life.

More importantly, Seitz wants it known how much his colleagues were there during that low time in his life. He says, "I love Armond. I love Godfrey. And I'm sure I'm quite aware of everybody who might have a problem with either of them for whatever reason. But they were hugely important to me as colleagues and, also, as mentors of a type. And I found them to be very compassionate towards me as a fellow writer. In fact, both of them were very supportive during that period after I lost Jen, you know. Just because we weren't writing anymore didn't mean I never spoke to them."

And, then, there was Armond.

To say Armond White was the most controversial critic out of this trio would be an understatement. (Seitz says, out of the three of them, White got the most hate mail.) His notoriously contrarian views on films and filmmaking—something that already made him a provocative figure when he was arts editor at The City Sun—was something Cheshire thought would work perfectly on the pages of the Press.

White became the critic readers disagreed with the most—and, yet, couldn't stop reading. His columns usually went after empty studio junk and overrated films (and filmmakers) that he felt weren't worth the box-office receipts. (One of my favorite White pieces, which isn't in the book, had him slamming the hell out of future Oscar winner "American Beauty" while giving a double-rave of Lawrence Kasdan's "Mumford" and Alan Rudolph's "Breakfast of Champions.") Also, as an African-American film critic, he often went after Hollywood for its myriad instances of covert/overt racism.

"My approach to being a film critic," explains the Detroiter-turned-New-Yorker White, "being part of a profession where there are thousands, is that there's no point in being a critic if you're gonna say what other people are already saying. There's no point. Why should I repeat what someone else has said? I am interested in expressing my own responses to film. And I guess that also means that, when I read other critics, I often find their responses wanting—that there's something else that needs to be said about a particular movie. And the New York Press allowed me that freedom."

On many occasions, White would give his own take on a movie that was already reviewed by his colleagues. At several points in Gang, a review from Cheshire or Seitz is immediately followed by a (usually negative) counterpoint from White. "We had a certain policy at New York Press where we would divide the new releases among the three of us," he remembers. "But, as I tried to indicate before, one of the things that I appreciated about the New York Press was that they gave us the freedom to write. And what that means to me is the opportunity to express myself."

White didn't hate everything. Much like Cheshire and Seitz, he has a soft spot for anything Steven Spielberg (whom he's currently writing a book on, titled Make Spielberg Great Again), Terrence Malick or the late Robert Altman created, as well as the work of international filmmakers like Wong Kar-Wai and Andre Techine. But it's his pans of universally acclaimed films and raves of not-so-beloved films—something he continues to this day over at National Review—that often has readers wondering if he does this just to get a rise out of people. "I am a serious critic," he says in a mock-exasperating tone. "This is serious to me. And I am not of the generation where there was an Internet and anybody who had a keyboard would be able to pretend to be a film critic and blurt their opinions. I work at this. I take it seriously and I don't do it just to get attention. I think that's a bizarre perspective from people, I suspect, of the Internet generation—they don't know what it means to cherish a writing position. They take it for granted because they have easy access to the Internet and they think because they do it, because they are simply trying to get attention, they think that everyone else is simply trying to get attention.

"I'm not doing it to get attention," he continues. "If I get attention, I hope it's because I said something that makes people think and I said something that's worth reading—not just to get a response from people. To me, that's childish and only children would think that way."