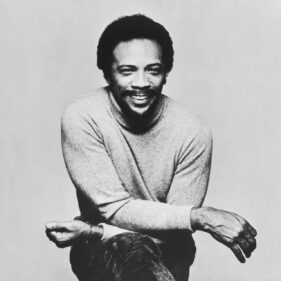

The go-getters, the losers, the sexually frustrated: these were the kinds of men that George Segal portrayed during his star period of the 1970s. In general he played nice guys, but with just enough psychic damage that they might be capable of very bad behavior and feel bad and guilty about it afterward. Segal's self-reproaches could approach the delirious in modern comedies of manners like Irvin Kershner's "Loving" (1970) and Paul Mazursky's "Blume in Love" (1973), but his hysteria, both suppressed and finally unleashed, was always controlled by an estimable technique. A Segal character was never going to get so out of hand that the actor would totally lose himself; there always seemed to be a kind of moral intelligence and striving after decency pulling the strings for his characterizations, even when the men he played were at their most contemptible.

The child of Jewish parents, Segal was raised in a secular household in Great Neck, New York. He first thought of becoming an actor when he saw Alan Ladd's angel of death killer in "This Gun for Hire" (1942), and what he liked best about Ladd in that movie was his dreamy lack of reality, that he was all image, all illusion. Segal went to Columbia College and worked in bands where he played the banjo, and he also played his Dixieland music while he served in the US Army.

Like so many of his generation, Segal studied at the Actors Studio, and he was an understudy for a Broadway production of "The Iceman Cometh." During his apprenticeship, Segal also worked in an improvisational group with Buck Henry, and he gravitated toward comic roles. As he reached the age of 30, Segal's career built impressively to two credits in 1966 where he played supporting roles in film adaptations of great American plays: as Biff on TV opposite Lee J. Cobb in Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman," and as Nick in the movie of Edward Albee's "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?"

George Grizzard had played Nick in the original Broadway production of "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" with Arthur Hill and Uta Hagen, with whom Segal had studied. But Segal was closer to the blond golden boy that Albee had first imagined, and he brings exactly the right amount of good boy striver mixed with opportunistic sleaze to the part, particularly in a scene where he gets progressively drunker and tells George (Richard Burton) about how he is ready to sexually service some "pertinent wives" on campus in order to advance his academic career.

As George moves in for the kill and starts to verbally tear Nick and his wife Honey (Sandy Dennis) apart, Segal reveals a sympathetic weakness and then a nearly impartial decency when he says, "I think I understand this" at the end of the film, as the games that George and his own wife Martha (Elizabeth Taylor) play about their fictional son become pitifully apparent. This was a virtuoso performance from Segal, playing the most difficult part in that major play by Albee, and it set him up for more challenges.

Segal regularly played his banjo on "The Tonight Show" for Johnny Carson and even released some records of Dixieland jazz with his band, but this was a side gig next to his leading man performances on film in what became increasingly dark sexual comedies in the 1970s. He could do outright farce like Carl Reiner's "Where's Poppa?" (1970), where he sparred with Ruth Gordon as his senile mother and went into agonies of sexual frustration that were only exacerbated by the scene in which Gordon exulted over his bare ass and kissed it on camera. And Segal could reveal all the human weakness of a philandering male in "Loving," in which he let down his lovely wife (Eva Marie Saint) in such a profound way that it was reminiscent of the most unsparing John Cheever short stories.

As a struggling writer who calls himself Felix in "The Owl and the Pussycat" (1970), Segal was maybe the strongest scene partner that Barbra Streisand ever had, and he does not shy away from all of the hard edges of the lofty and failed man he is playing. That was the rare magic of Segal at this time in movies: that he could reveal so many unattractive and defensive things about his characters without ever losing our sympathy, and without ever losing sight of the niceness in them that has been crushed. His chemistry with Streisand is off the charts here in the middle of this movie, so much so that they make a literary conceit about opposites that attract into a very gritty and believable screwball comedy.

Segal made several "battle of the sexes" pictures opposite a snarly Glenda Jackson, letting his sweet side absorb some of her nastier sniping, and his movie career came to a peak with "Blume in Love," in which he plays a man so obsessed with his ex-wife (Susan Anspach) that he is driven to do something unforgivable. In Robert Altman's "California Split" (1974), Segal and Elliott Gould played gamblers who approach life with all the spacy philosophy of born losers, and that's what Segal so excelled at in this period, the American male driven to despair by so much possibility for easy gratification and so little hope for anything that might prove more deeply satisfying.

It all started to come apart for Segal when he pulled out of playing the lead in Blake Edwards's comedy "10" (1979) and wound up being sued by Edwards; his first marriage was falling apart, and he later admitted to some problems with drugs. By the end of the 1980s, Segal was having to make due with the role of the selfish man that Kirstie Alley is having an affair with in "Look Who's Talking" (1989), and he was gradually eased into character roles rather than leads. He showed all of his old talent in a featured part in "For the Boys" (1991), where he was especially memorable in an extended scene where he tells off the men who have blacklisted him as a writer, and he was most at home in David O. Russell's "Flirting with Disaster" (1996), which had some of the comic overdrive of his best 1970s work. But when he worked with Streisand again in "The Mirror Has Two Faces" (1996), he had sadly been demoted from her leading man to a small character role.

Segal also worked regularly on sitcoms, most notably on the long-running "Just Shoot Me," and so he served his time and paid his dues as an older actor. There must have been moments when he wondered if anybody remembered what he was capable of as a performer from 1966 to 1980 or so. Past the age of 50, Segal didn't get the parts that he might have, maybe because he had been a star but he wasn't naturally a dominant or go-getting type himself. He remains an emblem of American cinema in the 1970s: a little desperate, worn around the edges, capable of madness, even, but with such battered good nature underneath.