"Girl With a Pearl Earring" is a quiet movie, shaken from time to time by ripples of emotional turbulence far beneath the surface. It is about things not said, opportunities not taken, potentials not realized, lips unkissed. All of these elements are guessed at by the filmmakers as they regard a painting made in about 1665 by Johannes Vermeer. The painting shows a young woman regarding us over her left shoulder. She wears a simple blue headband and a modest smock. Her red lips are slightly parted. Is she smiling? She seems to be glancing back at the moment she was leaving the room. She wears a pearl earring.

Not much is known about Vermeer, who left about 35 paintings. Nothing is known about his model. You can hear that it was his daughter, a neighbor, a tradeswoman. You will not hear that she was his lover, because Vermeer's household was under the iron rule of his mother-in-law, who was vigilant as a hawk. The painting has become as intriguing in its modest way as the Mona Lisa. The girl's face turned toward us from centuries ago demands that we ask, who was she? What was the thinking? What was the artist thinking about her?

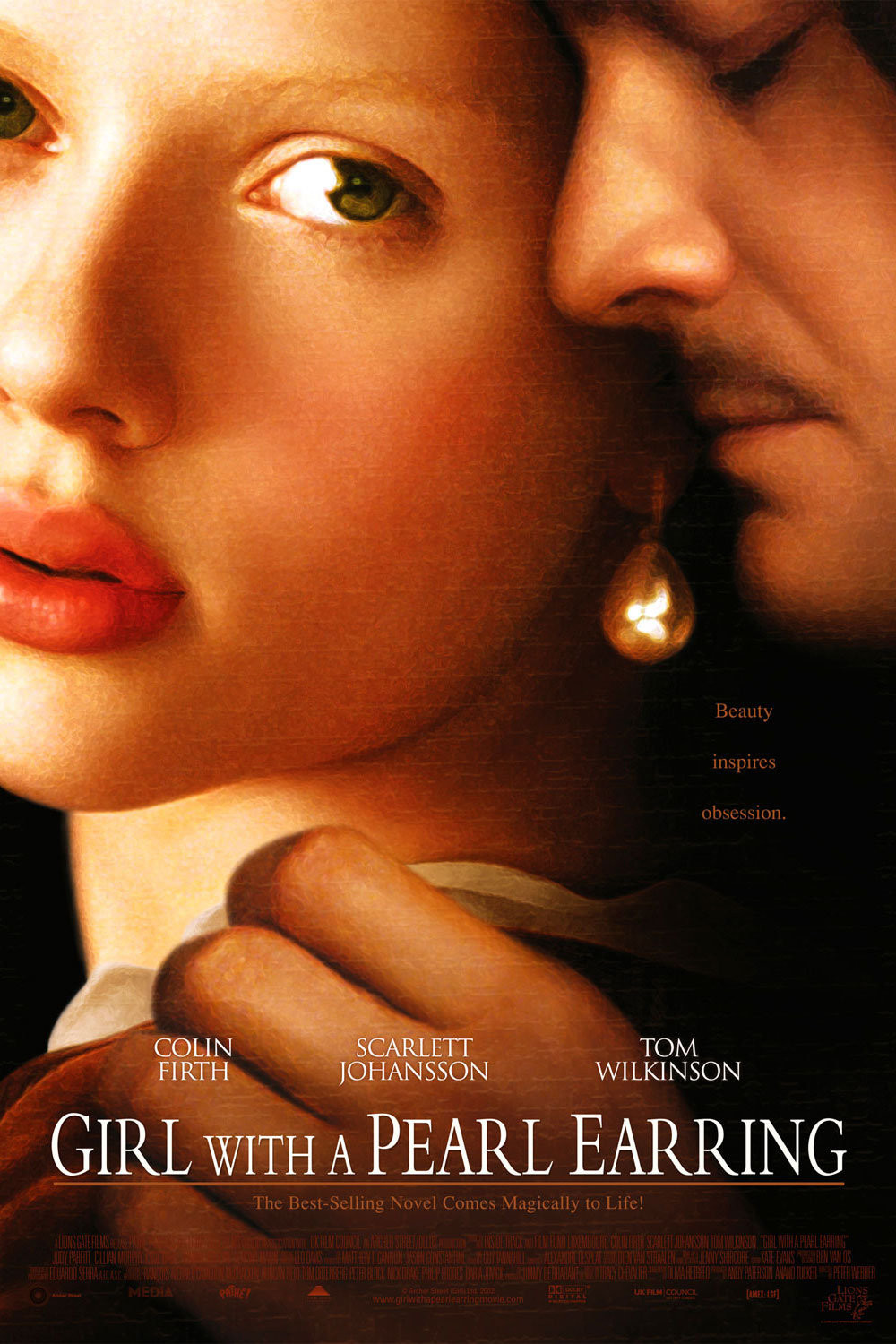

Tracy Chevalier's novel speculating about the painting has now been filmed by Peter Webber, who casts Scarlett Johansson as the girl and Colin Firth as Vermeer. I can think of many ways the film could have gone wrong, but it goes right, because it doesn't cook up melodrama and romantic intrigue but tells a story that's content with its simplicity. The painting is contemplative, reflective, subdued, and the film must be, too: We don't want lurid revelations breaking into its mood.

Sometimes two people will regard each other over a gulf too wide to ever be bridged, and know immediately what could have happened, and that it never will. That is essentially the message of "Girl with a Pearl Earring." The girl's name is Griet, according to this story. She lives nearby. She is sent by her blind father to work in Vermeer's house, where several small children are about to be joined by a new arrival. The household is run like a factory with the mother- in-law, Maria Thins (Judy Parfitt) as foreman. She has set her daughter to work producing babies while her son-in-law produces paintings. Both have an output of about one a year, which is good if you are a mother, but not if you are a painter.

Nobody ever says what they think in this house, except for Maria, whose thoughts are all too obvious, anyway. Catharina (Essie Davis), Vermeer's wife, sometimes seems to be standing where she hopes nobody will see her. It becomes clear that Griet is intelligent in a natural way, but has no idea what to do with her ideas. Of course she attracts Vermeer's attention; she's a hard worker and responds instinctively to the manual labor of painting -- to the craft, the technique, the strategy, even the chemistry (did you know that the color named Indian yellow is distilled from the urine of cows fed on mango leaves?).

In one flawless sequence, Griet is alone in Vermeer's studio and looks at the canvas he is working on, looks at what he is painting, looks back, looks forth, and then moves a chair away from a window. When he returns and sees what she has done, he studies the composition carefully and removes the chair from his painting. Eventually he has her move up to the attic, closer to his studio, where she can mix his paints, which she does very well.

And then of course they start sleeping together? Not in this movie. Vermeer has a rich patron named Van Ruijven (Tom Wilkinson). If Vermeer is too shy to reveal feelings for his maid, Van Ruijven is not. He wants a painting of the girl. This of course would be unacceptable to Catharina Vermeer, whose best-developed quality is her insecurity -- but it is not unacceptable to her mother, who must keep a rich patron happy. Thus Griet becomes a model.

There is a young man in the town, Pieter (Cillian Murphy), a butcher's apprentice, who is attracted to Griet. He would make her a good husband, in this world where status and opportunity are assigned by caste. Griet likes him. It's not that she likes Vermeer more; indeed, she's so intimidated she barely speaks to the artist. It's that -- well, Griet could never be a butcher, but she could be a painter.

Mankind has Shakespeares who were illiterate, Mozarts who never heard a note, painters who never touched a brush. Griet could be a painter. Whether a good or bad one, she will never know. Vermeer senses it. The moments of greatest intimacy between the simple peasant girl and the famous artist come when they sit side by side in wordless communication, mixing paints, both doing the same job, both understanding it.

Do not believe those who think this movie is about the "mystery" of the model, or Vermeer's sources of inspiration, or medieval gender roles, or whether the mother-in-law was the man in the family. A movie about those things would have been a bad movie. "Girl With a Pearl Earring" is about how they share a professional understanding that neither one has in any way with anyone else alive. I look at the painting and I realize that Griet is telling Vermeer, without using any words, "Well, if it were my painting, I'd have her stand like this."