This is the second Great Movies book, but the titles in it are

not the second team. I do not believe in rankings and lists, and refuse all

invitations to reveal my "ten all-time favorite musicals," etc., on

the grounds that such lists are meaningless and might well change between

Tuesday and Thursday. I make only two exceptions to this policy: I compile an

annual list of the year's best films, because it is graven in stone that movie

critics must do so, and I participate every ten years in the Sight & Sound

poll of the world's directors and critics.

As

I made clear in the introduction to the first Great Movies book, it was not a

list of "the" 100 greatest movies, but simply a collection of 100

great movies, unranked, selected because of my love for them, and for their

artistry, historical roles, influence, and so on. I wrote the essays in no particular

order, inspired sometimes by the availability of a newly-restored print or DVD.

To

be sure, the first book includes such obviously first team titles as

"Citizen Kane," "Singin' in the Rain," "The

General," "Ikiru," "Vertigo," the Apu Trilogy, "Persona,"

"2001: A Space Odyssey," "Potemkin," "Raging

Bull" and "La Dolce Vita." But because I was not writing in any

order, this second volume contains titles of fully equal stature, including

"Rules of the Game," "Children of Paradise," "The

Leopard," "Au Hasard Balthazar," "Birth of a Nation,"

"Sunrise," "Ugetsu," Kieslowski's "Three Colors"

trilogy, "Tokyo Story," "The Searchers," and

"Rashomon." In the case of the first two titles, I delayed a Great

Movie review until new DVDs were available, and felt with both "Rules of

the Game" and "Children of Paradise" that the prints had been so

wonderfully restored that I was essentially seeing the movies for the first

time.

I

have cited before the British critic Derek Malcolm's definition of a great

movie: Any movie he could not bear the thought of never seeing again. During

the course of a year I review about 250 films and see perhaps 200 more, and

could very easily bear the thought of not seeing many of them again, or even

for the first time. What a pleasure it is to step aside from the production

line and look closely and with love at films that vindicates the art form.

The

DVD has been of incalculable value to those who love films, producing prints of

such quality that the film can breathe before our eyes instead of merely

surviving there. The supplementary material on some of them is so useful and

detailed that today's audiences can know more about a title than, in some

cases, their directors knew when they were made. Of all directors, Martin

Scorsese has been the leader in assembling commentary tracks and supplementary

materials, not only for his own films but for others he loves; consider his

contribution to the DVDs of the films of Michael Powell, notably, in this book,

"The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp." To listen to Powell and

Scorsese as they watch the film together is a rare privilege.

I

have seen these movies in various times and places and ways, many of them three

or four times, some a dozen or twenty-five times. I've been through sixteen of

them a shot at a time, in sessions I conduct annually at the universities of

Colorado, Virginia and Hawaii, and at film festivals. The Colorado screenings,

part of the Conference on World Affairs, have been an annual event for going on

35 years. We sit in the dark in Macky Auditorium, sometimes as many as 1000 of

us, and take 10 or 12 hours over five days to go through a film with a

stop-action analysis. Remarkable, what you can see with all of those eyes.

Consider

my experience in 2003 with Ozu's masterpiece "Floating Weeds," which

was included in the first book, and which I once went through shot-by-shot at

the side of the great critic Donald Richie at the Hawaii Film Festival. In 2003

Criterion invited me to contribute a commentary track to their DVD of the film;

Richie would do the commentary on Ozu's earlier silent version. I asked myself,

frankly, whether I could talk for two hours about a film in which the director

never once moves his camera; with Ozu it is all placement, composition, acting

and editing. I suggested to Kim Hendrickson of Criterion that we take

"Floating Weeds" to Boulder as a sort of dress rehearsal. Some of the

audience members were less than thrilled by my choice, but then a wonderful

thing happened: Ozu's aura enveloped the audience, his genius drew them into

his work, and his style was seen, not as "difficult," but as

obviously the right way to deal with his material and sensibility. At the end

of the week, the watchers in that room loved Ozu, some of them for the first

time; sooner or later, if you care for the movies enough, you get to Ozu and

Bresson and Renoir and stand among the saints.

In

2004 I proposed Renoir's "Rules of the Game" at Boulder and again the

greatness of the film persuaded the reluctant ones in the audience (they had hoped

for "Kill Bill"--which would, for that matter, also be a good

choice). The more closely you look at Renoir's film, the better it becomes.

There are intricate movements of camera and actors that reveal astonishing

depths of beauty. The scene in the upstairs corridor when everybody turns in

for the night took us more than an hour to deal with, and even then we could

have continued. At the end of the week, I wrote about "Rules of the

Game" for this book.

I

look over the titles and my memory stirs. I saw "Kind Hearts and

Coronets" in London, during a revival of Ealing comedies. A restored print

of "The Leopard" was playing in London at the beloved Curzon cinema.

"The Man Who Laughs" played at the Telluride Film Festival, with a live

score by Philip Glass. "My Dinner with Andre" was also at Telluride,

and when the lights went up I found myself sitting right in front of Andre

Gregory and Wallace Shawn, who I wouldn't have recognized two hours earlier. I

saw "Patton" on a giant screen in the 70mm Dimension 150 projection

system at my own Overlooked Film Festival at the University of Illinois, and

after the screening Dr. Richard Vetter, the inventor of the system, joined me

onstage and said he had never seen it better projected. "Romeo and

Juliet" brought back memories of my night on the Italian location for the

filming of the balcony scene. "Touchez Pas au Grisbi" was in revival

in Seattle in December 2003, when I spent a month in the city for medical

treatments, and it and many other movies lifted me far above my problems. I

arrived at the film via "Bob le Flambeur," which is also in this

book; anyone who knows both films will understand how and why.

"Breathless" seemed as fresh to me in 2003 as it did when I saw it

the first time 40 years earlier. Viewing "Bring Me the Head of Alfredo

Garcia" for the first time since I put it on my annual best ten list in

1974, I was relieved to discover that I was absolutely correct about its

greatness.

The

most difficult film to deal with was Griffith's "The Birth of a

Nation." It contains such racism that it's difficult to press ahead with

the undoubted fact of its artistry and influence. I sidestepped it for the

earlier book; having taught it in my University of Chicago class, I dreaded

dealing with it again. In the event I wrote a two-part consideration of it, the

first part essentially an apologia. For this book I have combined and rewritten

that material. It is the only film in this book that doesn't, for me, pass the

Derek Malcolm test.

One

of my delights in these books, on the other hand, has been to include movies

not often cited as "great" -- some because they are dismissed as

merely popular ("Jaws," "Raiders of the Lost Ark"), some

because they are frankly entertainments ("Planes, Trains and

Automobiles," "Rififi"), some because they are too obscure

("The Fall of the House of Usher," "Stroszek"). We go to

different movies for different reasons, and greatness comes in many forms. Of

course there is no accounting for taste, and you may believe some of these

titles don't belong in the book. The reviewer of the first volume for The New

York Times Book Review ignored the introduction and the book jacket and

persisted in the erroneous belief that it was a list of "the" 100

greatest movies. He felt such a listing was fatally compromised by my inclusion

of Jacques Tati's "Mr. Hulot's Holiday" -- which was not, he

declared, a great film. Criticism is all opinion, so there is no such thing as

right and wrong, except in the case of his opinion of "Mr. Hulot's

Holiday," which is wrong. * * *

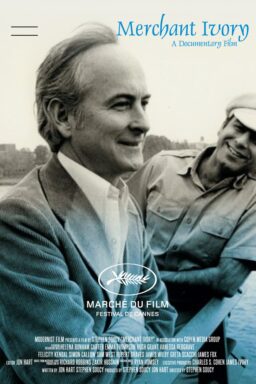

My

gratitude to my friend of many years, Mary Corliss, who once again drew on her

unequaled archival knowledge in selecting still photographs to reflect the

essence of the 100 films. Mary, her husband Richard, my wife Chaz and I have

had countless and endless movie conversations at Cannes, where we always stay

right down the hall from each other at Madame Cagnet's legendary Hotel

Splendid.

Thanks

also to Gerald Howard, my editor, who inspired the Norton anthology Roger

Ebert's Book of Film and at Broadway/Random House has been the steadying

hand for the Great Movies books. His knowledge of film is encyclopedic, his

taste is sure. When I hesitated to include "A Christmas Story" despite

my boundless affection for it, he assured me he could not imagine the book

without it.