There is a point in ''Hoop Dreams'' where the story, about two inner-city kids who dream of playing pro basketball, comes to a standstill while the mother of one of them addresses herself directly to the camera.

''Do you all wonder sometime how I am living?'' asks Sheila Agee. ''How my children survive, and how they're living? It's enough to really make people want to go out there and just lash out and hurt somebody.''

Yes, we have wondered. Her family is living on $268 a month in aid; when her son Arthur turned 18, his $100 payment was cut off, although he was still in high school. Their gas and electricity have been turned off in the winter. The family uses a camp lantern for light.

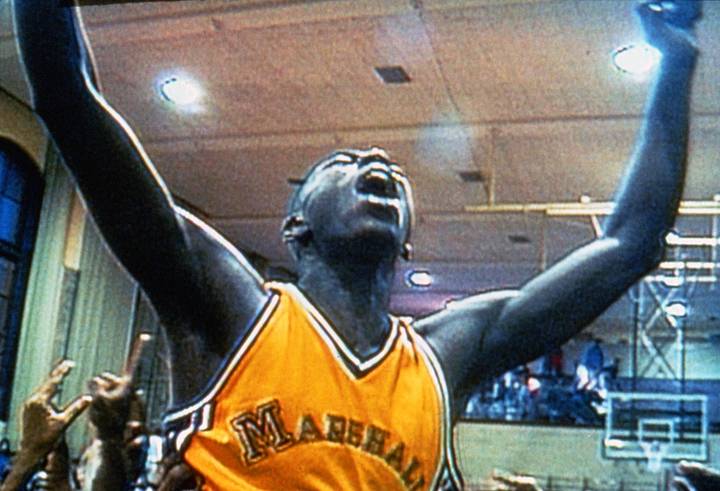

Arthur cannot graduate from Marshall, his Chicago high school, without transfer credits from St. Joseph's in suburban Westchester--the suburban school that recruited him, dropped him, and won't release the transcripts until $1,300 in back tuition is paid. Since this debt would not exist if scouts had not found Arthur on a playground and offered him a scholarship, there is irony there. The rich school reaches into the city, not to help worthy students, but to find good basketball players. If they don't make the grade, they're thrown back in the pond. But then it's payback time. Arthur becomes a star at Marshall and helps them finish third in the state. St. Joseph's is eliminated earlier in the playoffs. And William Gates, the other kid who, as an eighth-grader, was recruited by the school, has missed months of playing time because of injuries. When Arthur plays in the state semifinals at the University of Illinois, both Gates and his coach, Gene Pingatore, have to sit in the crowd.

No screenwriter would dare write this story; it is drama and melodrama, packaged with outrage and moments that make you want to cry. ''Hoop Dreams'' (1994) has the form of a sports documentary, but along the way it becomes a revealing and heartbreaking story about life in America. When the filmmakers began, they planned to make a 30-minute film about eighth-graders being recruited from inner-city playgrounds to play for suburban schools. Their film eventually encompassed six years, involved 250 hours of footage, and found a reversal of fortunes they could not possibly have anticipated.

Early in the film, we see the young men get up at 5:30 a.m. for the 90-minute commute to the suburbs. One of them talks about St. Joseph's with its ''carpets and flowers.'' From the beginning, William Gates is more naturally gifted than Arthur Agee. He stars on the varsity as a freshman, while Arthur plays for the freshman team. William is quick, brilliant, confident; Pingatore compares him with his great discovery Isiah Thomas, the NBA star who was also recruited by St. Joseph's. Both students arrive at the school reading at a fourth-grade level, but Gates quickly makes up the lost time, suggesting that his neighborhood schools were to blame. Arthur makes slower progress, in classrooms and on the court. ''Coach keeps asking me, 'When you gonna grow?' '' he smiles. He is eventually dropped from the squad, loses his scholarship, and after two months out of school enrolls at Marshall.

Gates seems headed for stardom, but injuries strike him. A ligament is repaired in his junior year. Torn cartilage is removed. Maybe he returns to the court too soon. He injures himself again. He loses confidence. Meanwhile, at Marshall, Arthur grows into his game and leads the team to a brilliant season. But the spotlight is still on Gates. He attends the Nike All-American Summer Camp at Princeton, where promising prep stars are scrutinized by famous coaches (Joey Meyer, Bobby Knight) and lectured by Dick Vitale (a showboat) and Spike Lee (a harsh realist). Arthur spends that summer working at Pizza Hut at $3.35 an hour. Then comes the senior year where Arthur leads his team to the state finals.

Both young men are recruited by colleges. Gates, despite his injuries, gets an offer from Marquette that promises him a four-year scholarship even if he can never play. He takes it. Agee, whose grades are marginal, ends up at Mineral Area Junior College in Missouri. There are eight black students on the campus. Seven of them are basketball players, and live in the same house. If his grades are good enough, he can use this as a springboard to a four-year school (and he does).

The sports stories develop headlong suspense, but the real heart of the film involves the scenes filmed in homes, playgrounds and churches in the inner city. There are parallel dramas involving fathers: Arthur's leaves the family after 20 years, gets involved with drugs, spends time in jail, returns, testifies in song at a Sunday service, but does not quite regain his son's trust. William's father has been out of the picture for years; he runs an auto garage, is friendly when he sees his son occasionally. The mothers are the key players in both families--and we also glimpse an extended family network that lends encouragement and support.

Every time I see ''Hoop Dreams,'' I end up thinking of Arthur's mother Sheila as the film's heroine. During the course of the film her husband leaves and gets into trouble, she suffers chronic back pain, she loses a job and goes on welfare, Arthur is dropped by St. Joseph's--and then, in the film's most astonishing revelation, we discover she has graduated as a nurse's assistant, with the top grades in her class.

There are moments in the film where the camera simply watches, impassively, as we arrive at our own conclusions. One is when Arthur and his parents visit St. Joseph's to get his transcripts, and are told they need to come up with a payment plan. ''Tuition provides 90 percent of our income,'' a school official says. Yes, but the school was not looking for tuition when it recruited Arthur; it was looking for a basketball player, and when it didn't get the player it expected, it should have had the grace to forgive him his debts.

Coach Pingatore and the school were parties to a suit to prevent the film from being released theatrically. The school comes off looking pragmatic and cold, but then ''Hoop Dreams'' reflects a reality that is true all over America, and not just at St. Joseph's. As for Pingatore, I think he comes across pretty well. He has his dream, too, of finding another Isiah Thomas. He wants to win. His record shows he is a good coach. He gives William sound advice, although perhaps he's too eager to see him return after his injury. William tells the filmmakers that the coach thinks sports are all-important, but I covered high school sports for two years and never met a coach who didn't. After saying farewell to William, Pingatore observes ''One goes out the door, and another one comes in the door. That's what it's all about.'' There is sad poetry there.

The movie was produced by the team of director Steve James, cinematographer Peter Gilbert and editor Frederick Marx. They benefitted from a remarkable intersection of opportunity and luck. They could not have known when they started how perfectly the experiences of Agee and Gates would generate the story they ended up telling. Over the years, there have been updates on their progress. William played for Marquette for four years and graduated; he did social work while supporting his wife's college education, then planned to return to law school. Arthur got into Arkansas State, played two years, has done some movie acting, has formed a foundation to help inner city kids get to college. Neither one played for the NBA. (Of the 500,000 kids playing high school basketball in any given year, only 25 do.) But their hoop dreams did come true.