When Carole Lombard and the family maid discuss the newly hired butler, we can read her mind when she says, "I'd like to sew his buttons on sometime, when they come off." In 1936, when elegant men's formalwear didn't use zippers, audiences must have had an even better idea of what she was thinking. The two women both have crushes on Godfrey (William Powell), a homeless man who Lombard, competing in a scavenger hunt, discovers living at the city dump. Lombard wins the hunt by producing Godfrey at a society ball and then, during an argument with her bitchy sister and loony mother, hires him to be the butler for her rich family. "Do you buttle?" she asks him, so crisply and directly that she could mean anything, or everything. Her romantic obsession is hopeless because Godfrey has transformed himself overnight from an unshaven bum into a polished, sophisticated man who prides himself on his proper behavior. When she grabs him and kisses him, he regards her with utter astonishment.

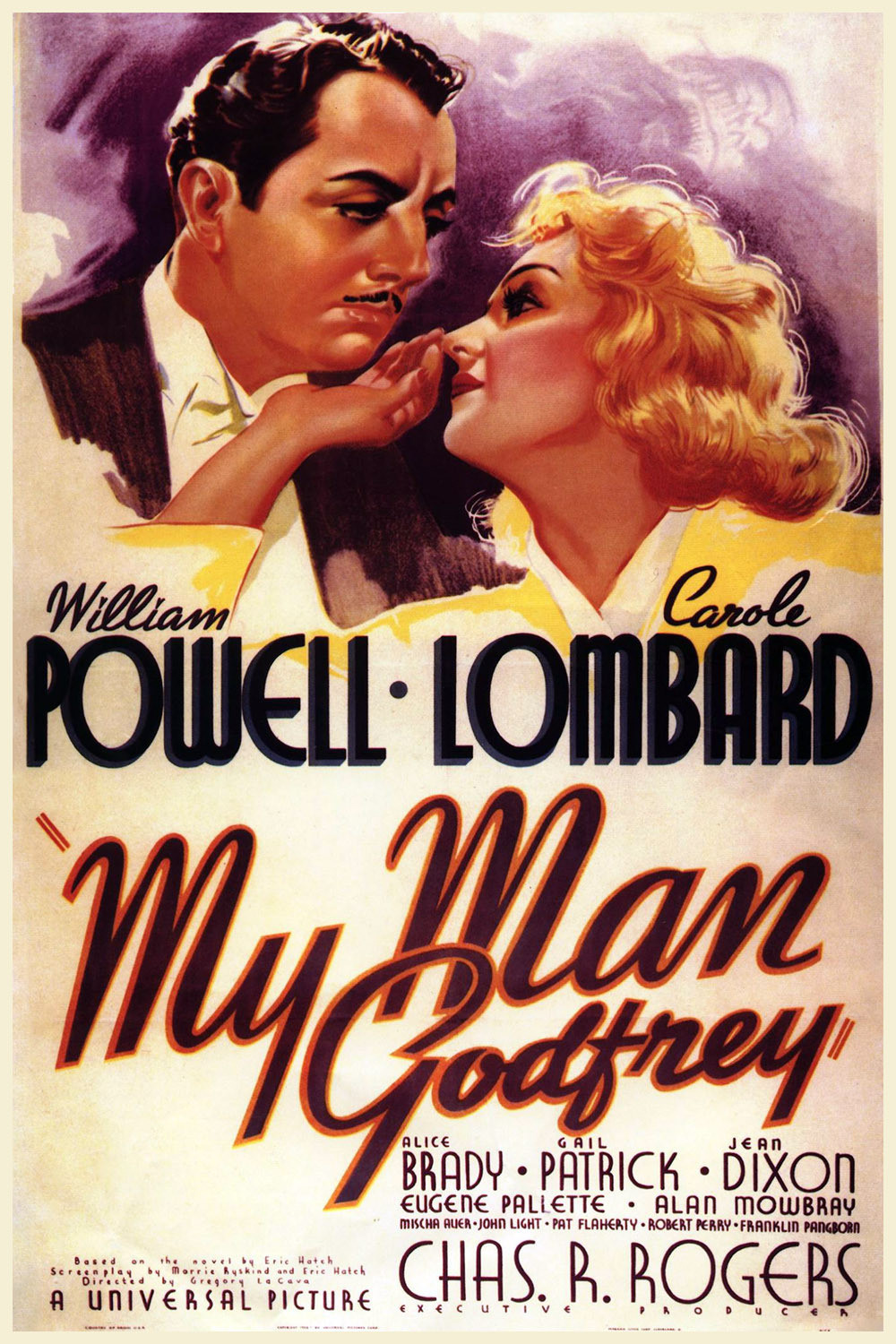

"My Man Godfrey," one of the treasures of 1930s screwball comedy, doesn't merely use Lombard and Powell, it loves them. She plays Irene, a petulant kid who wants what she wants when she wants it. His Godfrey employs an attentive posture and a deep, precise voice that bespeaks an exact measurement of the situation he finds himself in. These two actors, who were briefly married (1931-33) before the film was made in 1936, embody personal style in a way that is (to use a cliché that I mean sincerely) effortlessly magical. Consider Powell, best known for the "Thin Man" movies. How can such reserve suggest such depths of feeling? How can understatement and a cool, dry delivery embody such passion? You can never, ever catch him trying to capture effects. They come to him. And Lombard in this film has a dreamy, ditzy breathlessness that shows her sweetly yearning after this man who fascinated her even when she thought he really was a bum.

Like Preston Sturges' "Sullivan's Travels" (1941), Gregory La Cava's "My Man Godfrey" contrasts the poverty of "forgotten men" during the Depression with the spoiled lifestyles of the idle rich. The family Irene brings Godfrey home to buttle for is the Bullocks, all obliviously nuts. Her father, Alexander (that gravel-voiced character actor of genius, Eugene Pallette), is a rich man, secretly broke, who addresses his spendthrift family in tones of disbelief ("In prison, at least I'd find some peace"). Her mother, Angelica (Alice Brady), pampers herself with unabashed luxury and even maintains a "protégé" (Mischa Auer) whose duties involve declaiming great literature, playing the piano, leaping about the room like a gorilla and gobbling up second helpings at every meal. Her sister Cornelia (Gail Patrick) is bitter because she not only lost the scavenger hunt but got pushed into an ash heap after insulting Godfrey. And there is the maid, Molly (Jean Dixon), who briefs Godfrey on the insane world he is entering. She loves Godfrey, too, and perhaps down deep so does Cornelia, and so might the protégé, if he didn't like chicken legs more.

Godfrey buttles flawlessly, bringing Alexander his martinis a tray at a time, whipping up hors d'oeuvres in the kitchen and keeping his secret. He has one. Unmasked by a Harvard classmate at a party, he turns out to be born rich but down on his fortune after an unhappy romance. The Bullocks never figure out he's too good to be a butler (or a bum) because they're all blinded by their own selfishness, except for Irene, who dreams of his buttons. Under the surface, emotion is churning. Godfrey, having come to like and admire his fellow hobos at the dump, is offended that the Bullocks flaunt their wealth so uselessly, and that leads to one of those outcomes so beloved in screwball comedy, so impossible in life.

God, but this film is beautiful. The cinematography by Ted Tetzlaff is a shimmering argument for everything I've ever tried to say in praise of black and white. Look me in the eye and tell me you would prefer to see it in color. The restored version on the Criterion DVD is particularly alluring in its surfaces. Everything that can shine, glimmers: the marble floors, the silver, the mirrors, the crystal, the satin sheen of the gowns. There is a tactile feel to the furs and feathers of the women's costumes, and the fabric patterns by designer Louise Brymer use bold splashes and zigs and zags of blacks and whites to arrest our attention. Every woman in this movie, in every scene, is wearing something that other women at a party would kill for. These tones and textures are set off with one of those 1930s apartments that isintendedto look like a movie set, all poised for entrances and exits.

I found myself freezing the frame and simply appreciating compositions. Notice a shot when Godfrey exits screen right and the camera pans with him and then pushes to poor, sad Irene, seen through sculptured openings in the staircase and chewing the hem of her gown. Look for another composition balanced by a light fixture high on the wall to the right. You'll know the one.

A couple of reviewers on the Web complain that the plot is implausible. What are we going to do with these people? They've obviously never buttled a day in their lives. What you have to observe and admire is how gently the film offers its moments of genius. Irene has a mournful line something like, "Some people do just as they like with other people's lives, and it doesn't seem to make any difference ... to some people." Somehow she implies that the first "some people" refers to theoretical people, and the second refers to other people in the room.

Her futile love for Godfrey shows itself in the scene where he's doing the dishes in the kitchen, and she says she wants help: "I want to wipe." I know, it sounds mundane in print, but the spin she puts on it brings buttons back to our minds.

The "implausibility" involves the complications of a theft of pearls, some swift stock market moves, and Godfrey's plans for the city dump. OK, it's all implausible. That's what I'm here for. By pretending the implausible is possible, screwball comedy acts like a tonic. Nothing is impossible if you cut through the difficulties with an instrument like Powell's knife-edged delivery. He betrays little overt emotion, but what we glimpse is impatience with some people who will not do the obvious and, indeed, the inevitable.

The movie also benefits from the range of sharply defined characters, and the actors to play them. Even the biggest stars in those days were surrounded by other actors in substantial roles that provided them with counterpoint, with context, with emotional tennis partners. Notice here the work of Eugene Pallette, who bluntly speaks truth even though his family is deaf to him. By God, he's had enough: "What this family needs is discipline. I've been a patient man, but when people start riding horses up the front steps and parking them in the library, that's going a little too far. This family's got to settle down!" His voice is like a chain saw, cutting through the vapors around him.

This movie, and the actors in it, and its style of production, and the system that produced it, and the audiences that loved it, have all been replaced by pop culture of brainless vulgarity. But the movie survives, and to watch it is to be rescued from some people who don't care that it makes a difference ... to some people.

"The Thin Man" is also reviewed in the Great Movies collection.