"You're tearing me apart! You say one thing, he says another, and everybody changes back again."

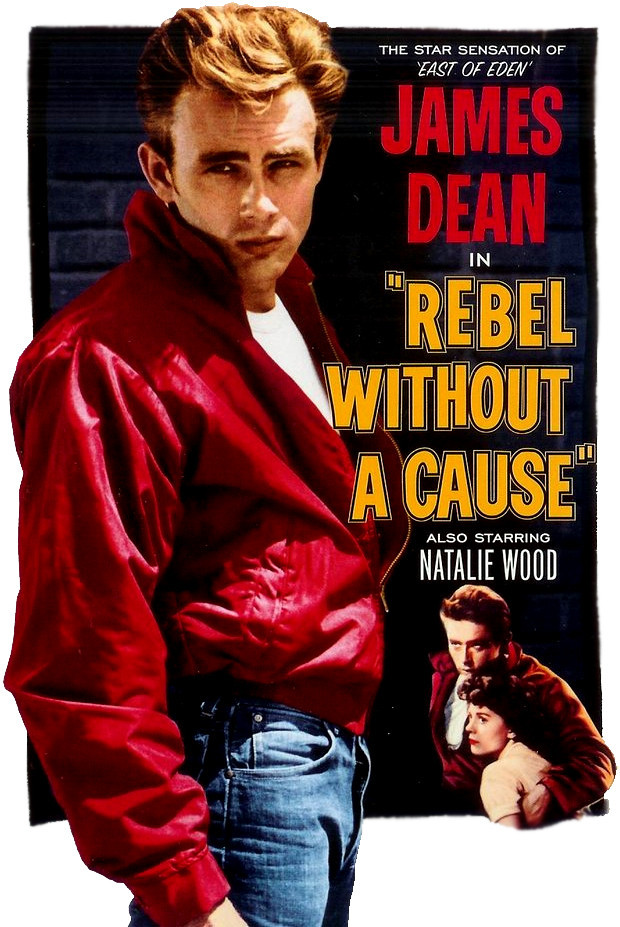

James Dean shouts these words in an anguished howl that seems to owe more to acting class than to his character, the rebellious and causeless Jim Stark in "Rebel Without a Cause." Because he died in a car crash a month before the movie opened in 1955, the performance took on an eerie kind of fame: It was the posthumous complaint of an actor widely expected to have a long and famous career. Only "East of Eden" (1954) was released while Dean was alive; "Giant," his last film, came out in 1956. And then the legend took over.

The film has not aged well, and Dean's performance seems more like marked-down Brando than the birth of an important talent. But "Rebel Without a Cause" was enormously influential at the time, a milestone in the creation of new idea about young people. Marlon Brando as a surly motorcycle gang leader in "The Wild One" (1953), James Dean in 1955, and the emergence of Elvis Presley in 1956: These three role models decisively altered the way young men could be seen in popular culture. They could be more feminine, sexier, more confused, more ambiguous.

"What can you do when you have to be a man?" Jim Stark asks his father, the emasculated Frank Stark (Jim Backus). But his father doesn't know, and in one grotesque scene, wears a frilly apron over his business suit while cleaning up spilled food. Jim comes from a household ruled by his overbearing mother (Ann Doran) and her mother (Virginia Brissac). Early in the film, he regards his father and tells a juvenile officer: "If he had guts to knock Mom cold once, then maybe she'd be happy, and she'd stop picking on him."

As causes go, Jim's doesn't rank with civil rights and war resistance, but the movie's point is that Jim is denied even a reason for his discontent. In the early 1950s, his unfocused rage fit neatly into pop psychology. The movie is based on a 1944 book of the same name by Robert Lindner, and reflected concern about "juvenile delinquency," a term then much in use; its more immediate inspiration may have been the now-forgotten 1943 book A Generation of Vipers, by Philip Wylie, which coined the term "Momism" and blamed an ascendant female dominance for much of what was wrong with modern America. "She eats him alive, and he takes it," Jim Stark tells the cop about his father.

Like Hamlet's disgust at his mother's betrayal of his father, Jim's feelings mask a deeper malaise, a feeling that life is a pointless choice between being and not being. In France at the time, that was called existentialism, but in Jim's Los Angeles, rebels were not so articulate. The first time Jim talks with Judy (Natalie Wood), the girl next door, she's ready for him. "You live here, don't you?" he says. "Who lives?" she says.

And consider the scene where Jim and his new enemy Buzz (Corey Allen) talk before the deadly game of "chicken" that will end with Buzz dead. Jim is the new kid in the high school, Buzz slashes his tire with a switchblade and challenges him to a "chickie run." The two kids will drive stolen cars toward a cliff, and the first one to bail out is the chicken.

Curiously, right before the race, Buzz tells Jim: "You know something? I like you."

"Why do we do this?" Jim asks.

"You got to do something?" says Buzz.

The philosophical stage for their duel was set earlier in the afternoon, during a class trip to the Griffith Park Observatory. The subject is "The End of Man," and the lecturer happily describes the sun growing larger until it explodes and wipes out all traces of mankind. "The Earth will not be missed," the lecturer informs the students. "Through the infinite reaches of space, the problems of man seem trivial and naive indeed, and man existing alone seems himself an episode of little consequence." This is not the note of optimism they require.

The observatory speech inspires a bitter aside from the movie's other major character, the small, angry and persecuted Plato (Sal Mineo): "What does he know about man alone?" It is clear now but may have been less visible in 1955 that Plato is gay and has a crush on Jim; at the planetarium, he touches his shoulder caressingly. After Buzz dies when his car hurtles over the cliff, the students all seem curiously -- well, composed. Jim gives Plato a lift home and Plato asks him, "Hey, you want to come home with me? I mean, there's nobody home at my house, and heck, I'm not tired. Are you?" But Jim glances in the direction of Judy's house, and then so does Plato, ruefully.

There is also sexual malaise in Judy's house. In a scene at dinner, she gives her father (William Hopper) a peck on the cheek, and he reacts with embarrassment: "What's the matter with you? You're getting too old for that kind of stuff. ... Girls your age don't do things like that." Judy responds: "Girls don't love their father? Since when? Since I got to be 16?" The implication is that her father is afraid of his sexual feelings for his daughter. To complete the collection of failed fathers, Plato's is dead or absent; his story changes from day to day, and he is being raised by a motherly black housekeeper.

Trying to deal with his role in Buzz's death, Jim tries to get guidance from his dad (still wearing the apron), gets in a fight with his parents and pauses on his way out of the house long enough to kick through an oil portrait of his mother, which has helpfully been left leaning on the floor next to the door. He's on his way to the police station to talk to a sympathetic juvenile officer, but is seen by Buzz's posse. They're angry with Jim, not because the race resulted in Buzz's death, but because they think he ratted on them to the police.

Hiding from them, Jim and Judy, followed by Plato, go to a deserted mansion near the observatory. And there they engage in a curious charade in which Plato becomes a real estate agent, and Jim and Judy play a couple being shown through the home. The subject of children comes up, and Plato advises against them, as being too noisy and bothersome. Jim agrees: "Drown 'em like puppies, eh?" He speaks in the voice of Mr. Magoo, the cartoon character voiced by Backus, who plays his father. This is beyond creepy. Later, in a tender scene, Plato goes to sleep at the feet of Jim and Judy, while she hums Brahms' "Lullaby" and Jim observes that they are like a family.

If I have quoted a lot from the movie, it's because the dialogue often seems to be making plot points that the director, Nicholas Ray, and the writer, Irving Shulman, may not have fully intended. Or perhaps they did, and guessed that some of the film's implications would not be fully recognized by 1955 audiences. Seen today, "Rebel Without a Cause" plays like a Todd Solondz movie, in which characters with bizarre problems perform a charade of normal behavior.

Because of the way weirdness seems to bubble just beneath the surface of the melodramatic plot, because of the oddness of Dean's mannered acting and Mineo's narcissistic self-pity, because of the cluelessness of the hero's father, because of all of these apparent flaws, "Rebel Without a Cause" has a greater interest than if it had been tidier and more sensible. You can sense an energy trying to break through, emotions unexamined but urgent.

Like its hero, "Rebel Without a Cause" desperately wants to say something and doesn't know what it is. If it did know, it would lose its fascination. More perhaps than it realized, it is a subversive document of its time.

A double feature of "Rebel Without a Cause" and "East of Eden," both in restored 35mm prints, will play June 24-30 at the Music Box Theatre, 3733 N. Southport. The movies are in general North American re-release.