The tension in "Samurai Rebellion" is generated by deep passions imprisoned within a rigid social order. The words and movements of the characters are dictated to the smallest detail by the codes of the time, but their emotions defy the codes. They move formally; their costumes denote their rank and function; they bow to authority, accept their places without question, and maintain ceremonial distances from one another. The story involves a marriage of true love, but the husband and wife are never seen to touch each other.

The visual strategy of the film reflects the rules of its world. The opening shots show architectural details, all parallel lines or sharp angles, no curves. It is the year 1725, in the Tokugawa Dynasty, which from 1603 to 1868 enforced a period of peace that depended on absolute obedience to authority. The story takes place in a remote district where Lord Matsudaira enforces his whims on all those beneath him.

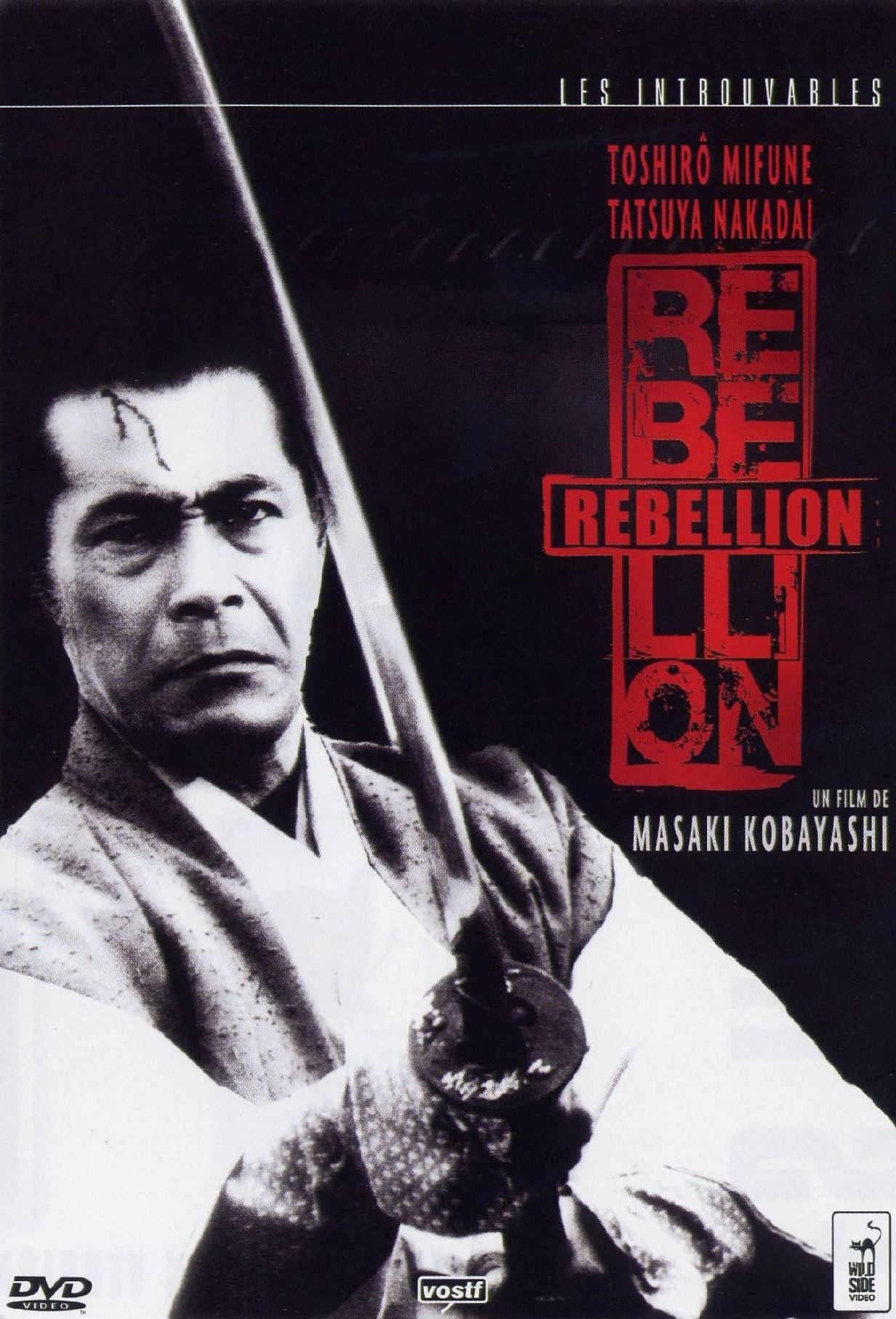

We meet the Sasahara household. We see its master, Isaburo (Toshiro Mifune) in an opening scene with his best friend, Tatewaki (Tatsuya Nakadai). More precisely, we see his sword, its point and then its blade, and then the focus shifts to show his fierce eyes behind it, and then shifts to the blade again. They stand in a field before a straw man, which Isaburo cuts in two with one blow. They are testing swords. Walking back home, they talk of their boredom, and Isaburo notes he has been "henpecked for 20 years."

Yes, this samurai warrior, said to be the deadliest swordsman of his clan, lives unhappily under the thumb of his wife. The film is so concerned with family life that in Japan it was released in 1967 as "Rebellion: Receive the Wife." This title was intended, says the critic Donald Richie, to attract women moviegoers who traditionally avoided samurai films. In America, the film was retitled "Samurai Rebellion," to attract martial arts fans. In the mind of its director, Masaki Kobayashi, its only title was "Rebellion."

It is a film of grace, beauty and fierce ethical debate, the story of a decision in favor of romance and against the samurai code. The plot involves the sexual convenience of the lord, who first forces the Sasahara family to accept his discarded mistress and then wants her back again. Lady Ichi (Yoko Tsukasa) was forced to become the lord's lover, bore him a son, and then in anger, struck the old man, pulled his hair and disgraced herself. The lord decrees she must be banished, and orders her to marry Yogoro (Go Kato), one of the two sons of the Sasaharas.

This does not please the family, but they obey the lord. After the marriage, Isaburo sees a way out of his unhappy subservience to his wife. He retires and names Yogoro head of the family. Yogoro explains to Ichi that his father dislikes his mother, "but has borne everything." Now Ichi will be the woman who manages the household: "You needn't hold back because of the old woman." To everyone's surprise, Ichi and Yogoro learn to love each other, and their marriage is blessed with a daughter named Tomi. When Yogoro asks his wife why she attacked the lord, she replies simply: "I felt as if a hairy worm was crawling over me."

Edicts from the lord are delivered by the steward (Shigeru Koyama). One day he arrives with news: The lord's heir has died, and the son he had by Ichi is the new heir to the throne. The steward says Ichi must leave the Sasaharas and return to the castle, for it would be improper for the heir's mother to be married to a vassal. As Ichi learns the news, we see her seated in the angle of two rice paper walls, ominous shadows crawling behind her like insects. She refuses to return. She is supported by her husband, and unexpectedly, by her father-in-law: Isaburo calls it a "cruel injustice," and tells them he has been moved by "your tender love for each other," so unlike his own marriage. So begins the rebellion of the title: Father, son and wife refuse to obey the lord, although Isaburo's wife Suga (Michiko Otsuka) and their other son are in favor of sending her back to the castle.

I was reading Anthony Trollope's Doctor Thorne when I saw the film, and was struck by how the two plots are similar in the way romance is opposed by a ruthless pragmatism, with social class being used to enforce what the characters should feel. The world of the samurai is far away from us, even further than Trollope's Barsetshire, but the feelings of the characters are universal and fundamental.

When we think of samurai movies, we think of swordplay, but "Samurai Rebellion" consists almost entirely of domestic life and diplomatic maneuvering until the film's final bloodbath. Isaburo believes he can protest the autocracy of the lord at the court of the emperor, in Edo, and the lord's steward is not eager to see this happen. A period of extraordinary negotiation opens, with bluff and counter-bluff, and we see family councils as the Sasahara relatives gather to try to talk the three rebels into accepting the lord's will. Lies are told, intrigues are carried out, Lady Ichi is kidnapped, and yet true love will not be denied.

There is also a curious change in the appearance of Mifune, the most famous of all Japanese stars. In early scenes, he looks so meek, so defeated by his marriage, that we hardly recognize him. As his resolve grows, as he supports Yogoro and Ichi, his famous face seems to take form, and he looks stern and angry, like the Mifune we know.

There is a key turning point. He is walking along the brick pathways in his enclosed stone garden. As he tells Ichi he will support her, he leaves the path, and his sandals make footprints in the carefully raked sand. He has broken the rules, refused to stay between the lines and placed his own will above that of the lord.

The director Masaki Kobayashi (1916-1996) was himself a rebel. I learn from Ephraim Katz's Film Encyclopedia that Kobayashi was a pacifist during World War II. After being drafted into the army and sent to Manchuria, "in a courageous act of personal defiance, he refused promotion and remained a private for the duration."

Defiance would be a subject of his films. His "The Human Condition" (1959) is a three-part, nine-hour film about a conscientious objector who serves in Manchuria just as Kobayashi did and acts not in obedience to the emperor but out of loyalty to his men.

He is best known for the elegant ghost stories in "Kwaidan" (1964) and the samurai drama "Harakiri" (1962), which many feel is better than "Samurai Rebellion."

Richie disagrees, praising Kobayashi's use here of 2:35-to-1 widescreen compositions to "even more effectively hem in his rebellious characters." The film's black-and-white cinematography is somber and beautiful, arranging the characters within visual boxes of space and architecture that reflect their relationships. Notice how when they are seated at meetings, their positions and body language precisely reflect their status, and how the departure of one character upsets the balance. Notice, too, the symbolism involved when Isaburo and his son prepare to do battle with the lord's men, and begin by disrupting the stark verticals and horizontals of the architecture with crisscrossed bamboo poles that make jagged barriers across the windows.

"Samurai Rebellion" can be seen as a statement against the conformity that remained central in Japanese life long after this period. It is the story of three people who learn to become individuals.

Consider the dramatic moment when the lord's steward returns to the Sasahara household, bringing with him the kidnapped Ichi, who has been ordered to plead for a divorce. She has been told the only alternative is that her husband and father-in-law will be ordered to commit seppuku, or suicide. Centuries of tradition require her to follow the script, but "They lie!" she cries out. "I am still the wife of Yogoro!"

The ending is tragic, resulting in death that is not glorious but obscure and hidden, leaving no record. Isaburo's dying words are gasps of advice to Tomi, his granddaughter. He tells her how brave her mother and father were, but Tomi is too young to understand. In another sense, the ending is triumphant: The three heroes of the story have expressed their will and their sense of right and wrong. We remember Isaburo shouting, "For the first time in my life I feel alive!"