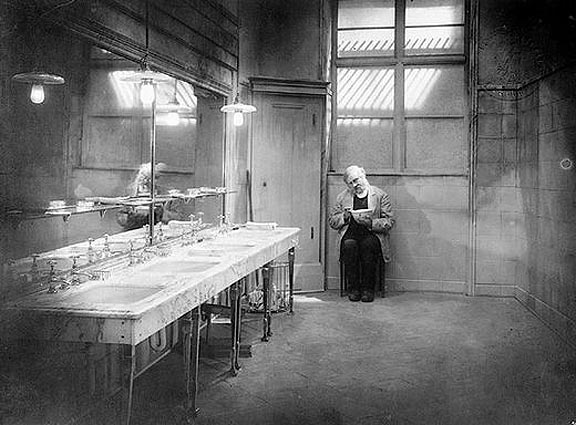

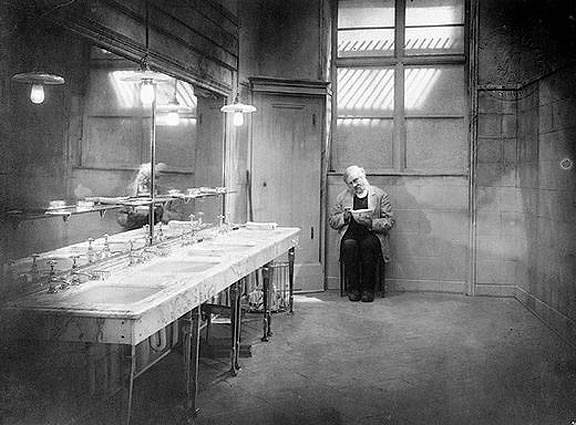

The old man is proud beyond all reason of his position as a hotel doorman, and even prouder of his uniform, with its gold braids and brass buttons, its wide shoulders, military lapels and comic opera cuffs. Positioned in front of the busy revolving door, he greets the rich and famous and is the embodiment of the great hotel's traditions--until, in old age, he is crushed by being demoted to the humiliating position of washroom attendant.

F.W. Murnau's "The Last Laugh" (1924) tells this story in one of the most famous of silent films, and one of the most truly silent, because it does not even use printed intertitles. Silent directors were proud of their ability to tell a story through pantomime and the language of the camera, but no one before Murnau had ever entirely done away with all written words on the screen (except for one sardonic comment we'll get to later). He tells his story through shots, angles, moves, facial expressions and easily read visual cues.

The film would be famous just for its lack of titles, and for its lead performance by Emil Jannings, which is so effective that both Jannings and Murnau were offered Hollywood contracts and moved to America at the dawn of sound. But "The Last Laugh" is remarkable also for its moving camera. It is often described as the first film to make great use of a moving point of view. It isn't, really; the silent historian Kevin Brownlow cites "The Second-in-Command," made 10 years earlier. But it is certainly the film that made the most spectacular early use of movement, with shots that track down an elevator and out through a hotel lobby, or seemingly move through the plate-glass window of a hotel manager's office (influencing the famous shot in "Citizen Kane" that swoops down through the skylight of a nightclub).

Murnau's technical mastery makes all of his films exciting to see. In the vampire movie "Nosferatu," in the fiendish visions of "Faust," in the imaginary city of "Sunrise," he created phantasmagoric visions that seemed to define his characters: They were who they were because of what surrounded them. This is a key to German Expressionism, the influential silent style that told stories through bold and exaggerated visual elements--reality slipping over into nightmare and back again.

In the case of "The Last Laugh," however, Murnau's story is more of a traditional narrative than usual. He follows the old doorman in almost every shot, cutting away only to show what the doorman sees. And he exaggerates the scale of the hotel and the city to emphasize how important it seems to the doorman; the opening shot, coming down in the elevator and tracking across the lobby (the camera was in a wheelchair), peers out through revolving doors into the rain, showing elegant people and glittering surroundings; the doorman is full of himself as he whistles for cabs and salutes arriving customers.

In those early scenes Murnau shoots the doorman from a low angle, so that he seems to tower over other characters. He is tall and wide, his face surrounded by a beard and whiskers that frame its cherubic pomp. But beneath the grand display his body is failing him, and we see him struggle with an enormous steamer trunk and then take a moment's rest in the lobby--just long enough for the prissy assistant manager to see him and write up a note. And the next day when he arrives for work, his world shakes and the camera swirls as he sees another man in uniform, doing his job.

Much of the doorman's happiness in life depends on the respect paid to his uniform by his neighbors around the courtyard of his apartment building. Murnau built this enormous set (most of the film, including rainy exteriors, was shot on sound stages) and peopled it with nosy busybodies who don't miss a thing. Ashamed to be seen without his uniform, the doorman actually steals it from a locker to wear it home. Later, when his deception is revealed, there is a nightmarish montage of laughing and derisive faces.

His tragedy "could only be a German story," wrote the critic Lotte Eisner, whose 1964 book on Murnau reawakened interest in his work. "It could only happen in a country where the uniform (as it was at the time the film was made) was more than God." Perhaps the doorman's total identification with his job, his position, his uniform and his image helps foreshadow the rise of the Nazi Party; once he puts on his uniform, the doorman is no longer an individual but a slavishly loyal instrument of a larger organization. And when he takes the uniform off, he ceases to exist, even in his own eyes.

Murnau was bold in his use of the camera, and lucky to work with Karl Freund, a great cinematographer who also immigrated to Hollywood. Freund filmed many other German silent films, notably Fritz Lang's futurist parable "Metropolis" (1926), and his first notable American film was "All Quiet on the Western Front" (1930). He was one of the links between German expression and its American cousin, film noir (see his work with John Huston and Humphrey Bogart in "Key Largo").

Here he liberated the camera from gravity. There is a shot where the camera seems to float through the air, and it literally does; Freund had himself and the camera mounted on a swing, and Abel Gance borrowed the technique a few years later for his "Napoleon." There are shots where superimposed images swim through the air, the famous shot that seems to move through the glass window, and a moment when the towering Hotel Atlantic seems to lean over to crush the staggering doorman.

I mentioned the one place in the film where a title card is used. It is not necessary, and the film would make perfect sense without it. But Murnau seemed compelled to use it, almost as an apology for what follows. We see the pathetic old man wrapped in the cloak of the night watchman who was his friend, and the movie seems over. Then comes the title card, which says, "Here the story should really end, for, in real life, the forlorn old man would have little to look forward to but death. The author took pity on him and has provided a quite improbable epilogue."

Improbable, and unsatisfying, because a happy ending is conjured out of thin air. The doorman accidentally inherits a fortune, returns to the hotel in glory and treats all his friends to champagne and caviar, while his old enemies glower and gnash their teeth. It is this ending that inspires the English language title. The original German is "Die Letzte Mann," or "the last man," which in addition to its obvious meaning may also evoke "the previous man"--the doorman who was replaced. The dimwitted practice of tacking a contrived happy ending onto a sad story was not unique with Murnau (who had the grace to apologize in advance for it), and has only grown more popular over the decades.

As for Emil Jannings (1884-1950), he made "The Last Laugh" at the top of his form; considered one of the world's greatest stars, he specialized in towering figures such as Peter the Great, Henry VIII, Louis XVI, Danton and Othello. The doorman's fall from grace was all the greater because the audience remembered the glory of his earlier roles. Jannings came to America at the same time as Murnau, won the Academy Award for "The Last Command" (1928), was rendered unemployable by the rise of the talkies, returned to Germany and found one of his most famous roles, as Marlene Dietrich's erotically mesmerized admirer in "The Blue Angel" (1930). Jannings embraced the rise of the Nazis, made films that supported them, was appointed head of a major German production company, and fell into disgrace after the war. The coat no longer fit.