Debuted earlier this year at Lincoln Center and now on a national tour, the 21-film series "Masterpieces of Polish Cinema" bears stunning testament to the brilliance of not only one especially fecund national cinema but an entire era of moviemaking—call it the golden age of the art film. As Martin Scorsese, who curated the series and whose Film Foundation provided its pristine digital restorations, has remarked, the period it covers (roughly the ‘50s through the ‘70s) was one of extraordinary accomplishments in many parts of the cinematic world, a high-water mark that grows ever more dazzling in retrospect.

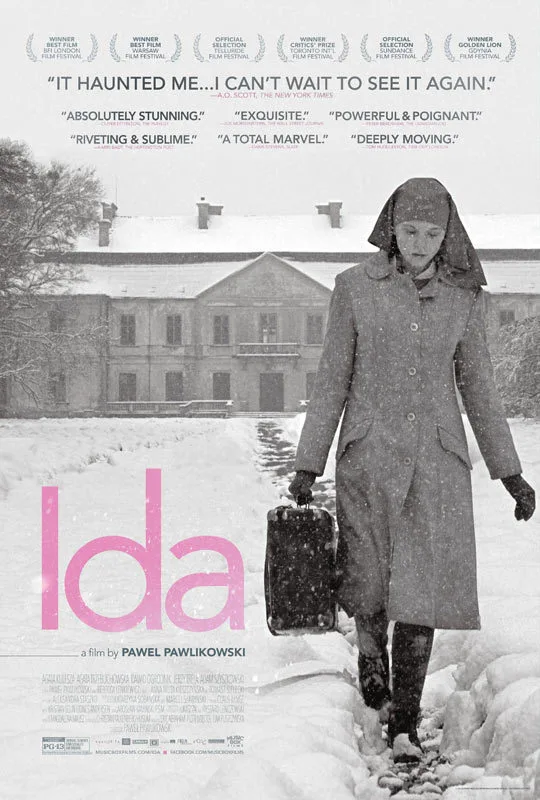

Set in the Poland of 1962 and composed of austerely gorgeous black and white images, Pawel Pawlikowski's "Ida" could fit right into the "Masterpieces" series, evoking as it does films ranging from Andrzej Wajda's "Innocent Sorcerers" to Jerzy Kawalerowicz's "Mother Joan of the Angels" (both 1960). But that's not to suggest it's a throwback or an exercise in cinematic nostalgia. Riveting, original and breathtakingly accomplished on every level, "Ida" would be a masterpiece in any era, in any country.

Somewhat ironically, director and co-writer Pawlikowski can't be considered a Polish filmmaker in any strict sense. Though born in Poland, he grew up in Great Britain and has done most of his work there (his previous films include "My Summer of Love" and "Last Resort"). "Ida" represents a return home for the filmmaker, one that he has said draws on the memories, sights and sounds of his childhood.

That retrospective, and somewhat impressionistic, viewpoint mirrors the film's own. Though set in the '60s, the era of Communist rule and modernization, the story scripted by Pawlikowski and Rebecca Lenkiewicz looks backward in time. Given that it starts out in a convent that seems like it hasn't changed since the Middle Ages, you might say that the film's perspective suggests a vast expanse of Polish history. But its main focus is closer to hand: the country's occupation by the Nazis (a historical passage that is resonantly evoked but never seen or directly referred to).

Anna (Agata Trzebokowska) is an 18-year-old orphan who was raised in that convent and is preparing to take her vows when her Mother Superior insists that first she meet her one known relative. That is an aunt, Wanda (Agneta Kulesza), a former prosecutor with a high Communist Party rank whose dissolute life of smoking, drinking and bedding men stands in stark contrast to the ascetic existence of her sheltered niece. But Anna has more to be shocked about when Wanda tells her that her real name is Ida (pronounced Eeda), that she is Jewish and that her parents were killed during World War II.

This revelation triggers a journey in which aunt and niece drive back to the village of Anna's parents in an effort to discover how they died and where they were buried. Although this quest is central to the narrative, "Ida" is anything but plot-driven. It's a film of moments, observations and moods, with a lyrical unfolding that recalls such atmospheric monochrome road movies as Wim Wenders' "Kings of the Road." And when the two voyagers pick up a hitchhiking tenor saxophonist (Dawid Ogrodnik) and end up watching his gigs, the music of John Coltrane and similar artists adds an engrossing aural dimension to the odyssey.

Few recent films can claim a visual approach as striking as that which cinematographers Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski give "Ida." Filmed in the unusual, boxy aspect ratio of 1.37:1, and most often deployed in static long shots, the film's images sometimes suggest Vermeer lighting with the color taken away, and the compositions manage to seem at once classical and off-handed, with the subjects often located in the screen's two bottom quadrants. As in Bresson, the effect is to draw the viewer's eye into the beauty of the image while simultaneously maintaining a contemplative distance from the drama.

Pawlikoski and Lenkiewicz's scripting proves similarly lapidarian. Besides its look, "Ida" most recalls the manner of bygone art films in the modernist spareness and thoroughgoing obliqueness of its writing. Very little is stated directly; instead, we glean things from casual remarks and subtle suggestions. Somehow, this technique of inference makes the film's eventual revelations feel both more integral and more powerful.

Because revelations do come, despite the quest's languorous rhythms, and they touch on arguably the darkest and most troubling chapter in modern Poland's history. What happened to Anna's parents? Most films that approach this horrific arena envision jackbooted armies and vast industrial execution sites. But in Poland in the '40s, as in Cambodia in the '70s and Rwanda in the '90s, evil's authors could be one's friends and neighbors, and simple farm implements its instruments. In touching on this reality, "Ida" adds something to a subject that sometimes seems to have lost the ability to disturb us as it should in movies.

Besides this historical acuity, the film gives us a fascinating pair of matched archetypes in its main characters, which are realized in two exquisite performances. As the aspiring nun who's suddenly tossed into the ugliness of the world, newcomer Agata Trzebokowska proves a poised icon of luminous quietude and awakened curiosity, discovering herself as she painfully uncovers her past. And as the embittered, nihilistic "Red Wanda," a woman driven both by the horrors inflicted on her and those she's inflicted on others, veteran Polish actress Agneta Kulesza creates the astonishing impression that some of history's most wrenching conflicts are being played out in a single human soul. Like much about "Ida," these actresses' work not only pays homage to masterpieces of the past but revivifies current cinema in doing so.