In anticipation of the Academy Awards, we polled our contributors to see what they thought should win the Oscar. Once we had our winners, we asked various writers to make the case for our selection in each category. Here, Omer Mozaffar makes the case for the best documentary of 2016: "I Am Not Your Negro." Two winners will be announced Monday through Thursday, ending in our choices for Best Director and Best Picture on Friday.

Raoul Peck's "I Am Not Your Negro" explores James Baldwin's mind as he worked on his final book, "Remember this House," reflecting on America through the stories of three slain close friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. The film shows us what he saw in our society in 1979, and what he would see today in 2017. It is a complex, unrelenting analysis of Race in America, through the eyes of one of the most complex, unrelenting thinkers this nation produced.

The American story is, for Baldwin, a story of two Americas. The first America is the glittering, imaginary Utopia that promises everyone a suburban house, nuclear family, and white fence. Because this is a White dream, the American Negro becomes both a benefit and a thorn. The White Supremacist fantasy justifies itself by portraying the American Negro as a savage, lazy, powerless, clown. On the other hand, considering the history of our subjugation of the American Negro, he becomes a daily reminder that the American dream is just that: a fantasy for the privileged who pretend—rather, insist—that places like Birmingham, Alabama are on Mars.

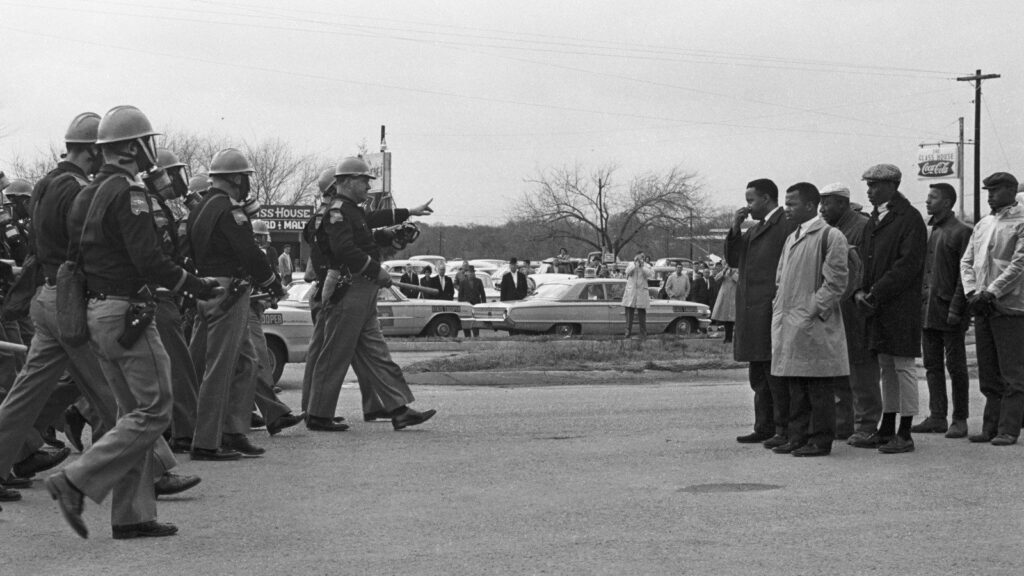

The other America is the real America. Baldwin tells us that America has given no place for the Negro, and in that, the history of the Negro is the history of America, from Slavery, to Reconstruction and Jim Crow, to the Civil Rights struggle. Further, history is the present, for the present is not only the result of history, but is also the lens through which we know history. Medgar Evers was the tireless servant seeking to develop Black American opportunities in business, education, and civic engagement. Malcolm X was the voice of Black suffering. King, his polar opposite, started carrying the burden of the nation from his twenties. In their final years, Malcolm and Martin merged. They were men of dignity seeking to ennoble and empower their populations, and for that they were dangerous. Each of them was gunned down before turning 40: Medgar, in front of his house, Malcolm, during a speech, and Martin, walking out of a hotel room. Through it all, we are able to ignore Black lives, Black neighborhoods, as though they do not matter.

Baldwin has the slim dark face of a young boy with large eyes. When he grins, his entire face beams. His voice has a slight husk from cigarettes, an intellectual accent, enunciating letters as though each word is deliberate. And his words are searing. Bobby Kennedy earns praise when he says in the 1960s that in forty years there could be an African-American President. Baldwin responds, saying that Kennedy just arrived and is himself almost the nation's leader, while African-Americans have been here for 400 years and are told that if they are good, they can be President. A sympathetic philosophy professor complains that Baldwin insists on the divisive lens of Race, when he has more in common with other white writers than with many African Americans. Baldwin replies that he walks with his life in danger, regarded as an enemy because of his race.

Peck's film is neither biography nor civil rights memoir. Rather, it is a set of chapters, with voice-over by Samuel L. Jackson, slowly reading Baldwin's statements, with images from interviews, cinema, advertising, and news footage. Sometimes, all three seam together. Baldwin speaks about watching a film, staring at an African-American janitor's pained face, learning about the murder of his daughter. Sometimes, all three clash, as cops beat Rodney King while an opera soundtrack seems mocking and sarcastic. Sometimes, he provides the commentary from African-American communities, who would realize (around age five) that in cowboy movies, they were not the hero, but villains he was firing at. Meaning, he was the voice of a people who could see through American bluster to its rotten, hypocritical core.

In capturing Baldwin's mind, his world, his vision, Peck's film's most powerful message is that nothing has changed. An African-American president might confirm the American dream, might complete American history. Yet, during his rule, numerous young African-American men and women were gunned down, by men in uniform. Thus, just as Baldwin was unable to finish his book, just as the dream of Black dignity and agency remains deferred, history continues living in the present, by not letting the present change, as though it keeps the present locked in rusted shackles. Locked.