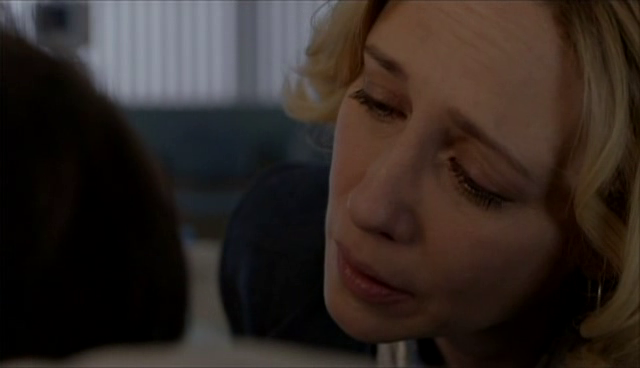

The season two finale of A&E's "Bates Motel," contains a quiet moment where the audience watches Norman Bates [Freddie Highmore] sleep, only for the camera to pull back and expose his worried mother, Norma [Vera Farmiga], keeping vigil, moving quietly in her rocking chair. This is far from the only callback to the film the series plays with but it may be the most representative of the core of the show: Norma Bates loves her son and will give her life to keep him safe. Yet as normal as this impulse would be on any other show, it serves as a radical departure for the assumed canon of the "Psycho" universe. To suggest that Norma Bates is a caring, if deeply flawed, mother flies in the face of everything audiences have come to understand about the Bates saga, a drastic left turn to such a well-known cultural staple. And it's that brilliant left turn that transforms a known quantity into something new and unexpectedly pathos-driven.

The evil mother figure is a well-worn trope in film and television alike, and Norma, as originally conceived, is no exception. A specter that haunts every corner of "Psycho," it's only with the inception of "Bates" that the audience comes to understand just how misrepresented Norma has been all these years. To say that Norman is an unreliable narrator in the film and the book that inspired it is an understatement at best. Through his eyes, we see a repressed, shrewish, near incestuous harpy hell-bent on bending a weak-willed son to her whims. The brilliance of "Bates" is how it chooses to reframe this narrative by building out the history that precedes not just the film's timeline but that of the series itself, refusing to settle for taking the word of a known psychopath.

As our understanding of Norma has expanded, so has our understanding of what Norman is since the novel was written in 1959 and the film was made in 1960. Despite the title, Robert Bloch never calls Norman a psychopath. He does, however, call Norma a man-hater who dominated her son and Norman a secret transvestite with a burgeoning interest in the occult. They're vivid descriptions, but they fall short of our, still evolving, understanding of psychopaths.

For instance, in "The Psychopath Inside" by neuroscientist James Fallon, the author recounts the experience of finding out that PET scans taken of his own brain showed identical earmarks to those of a typical psychopath. Fallon's research reveals that PET scans of diagnosed psychopaths have recognizable and identifiable patterns in the brain that could lead to greater understanding and identification of the group, potentially providing demonstrable, verifiable evidence of a psychopath. He also recounts stories from his life in which he exhibits careless, manipulative behavior, often with little care for the well being of others, including an incident involving a trip with his brother to Africa under the pretense of visiting Kitum Cave to see the elephants that gather, but in reality to afford Fallon the opportunity to visit a spot not yet widely known to be fostering a Marburg (an Ebola-type) virus, all unbeknownst to his brother.

While never blatantly malicious, Fallon recognizes how troubling such choices were for those around him, even while admitting he's not much bothered by their feelings. He categorizes himself first as a "prosocial psychopath" and then as a "lucky psychopath": lucky that he was raised in a positive, nurturing family with two parents who took care to create a safe environment for him to thrive.

That, then, would make Norman Bates an unlucky psychopath. But the whole of the blame for such an upbringing can hardly be placed solely on Norma. This is best evidenced in the film by that slightly excruciating scene near the end in which the psychiatrist explains just how Norman's psychotic break was due entirely to an overbearing mother. Conspicuously missing in the "Psycho" world is the presence of Norman's father. He's perhaps dead, certainly absent. "Bates" builds up his influence, showing him in flashback to be an angry, abusive man whom Norman eventually kills in an attempt to protect his mother from his father's onslaught. Being raised in such a chaotic, unstable environment and being exposed to such violence from such a young age is devastating to the psyche of even a psychologically sound child, much less one so apparently given to fracture as Norman. Fallon can attest as such, saying in his book,

"I looked at all the case studies I could find in the literature and in my work, and saw that for all the psychopaths, including dictators, who had psychiatric reports from their youth, all had been abused and often had lost one or more of their biological parents."

Norma is by no means a perfect parent, given as she is to intense overreaction and histrionics, but given her own personal history as spelled out by the series, this kind of behavior is understandable, if not acceptable. Herself suffering under an abusive father, paired with a present, but distant mother, she fell victim to a predatory older brother who raped her daily until she escaped through the guise of marriage. Said marriage, proved a frying pan/fire situation but, at the very least, it gave her her true love, Norman. Coupled with the murder she witnesses and the one she perpetrated on a man who had been raping her, it's not a stretch to say that for Norma the night is truly dark and full of terrors. She is paranoid that the world is out to get her because nothing in her life has given her reason to think otherwise. She's not wrong to feel that way, as in this universe worry is the best indicator of an occurrence's looming inevitability. For instance, Norma is right to worry about her son being alone with girls, as later evidenced by the revelation that his teacher seduced him before he murdered her during one of his blackouts.

This is why what "Bates" is doing with her and Norman's relationship is so fascinating. The two share an uncomfortable closeness, a squirm-inspiring intimacy bent on making the viewer uncomfortable. But in the context of "Bates Motel," such intimacy makes a perfect, if sick, sense. Norma and Norman cling to each other like the only survivors of a massive shipwreck. The season two finale is rife with instances of such intimacy, like Norma's loving, insistent caresses of Norman's face and hair after his near death. The camera focused so tightly, refusing even the relief of a two shot, alternating between the two, room enough in the frame for only one pained face at a time, each murmuring to the other. It is suffocating and unrelenting, forcing the audience to a place where it feels that breathless intimacy in their chest. This bond predates anything we've been privy to in the "Psycho" universe before and suggests a relationship forged in the fires of shared trauma. They are all the other has, even with the existence of Norma's older son, Dylan. Even that relationship serves to make sense of Norman and Norma's atypically close bond when it is revealed that Dylan was born from her brother's sexual assaults.

As soapy as those elements may be, they're all grounded in something familiar and true: Norman is left with his champion, his protector, all he has left in this world and Norma, broken down lioness though she may be, is desperate to protect her lame cub from the horrors in the world and in himself.

It is because she's the only one left to pick up the pieces of her wounded child's mind that the inevitable blame for Norman's condition falls to Norma, even as the context of "Bates" makes it increasingly clear that the parent to blame for the decimation of Norman's psyche is not the mother who worked at every turn to protect him but the father who ensured his childhood was filled with intimidation and violence. Robert Bloch, author of the novel "Psycho," referred to a triad that ruled Norman Bates' mind as "Norman," "Norma," and "Normal." He explained that Norman was the child, Norma the murderous mother, and Normal the functioning adult. "Bates" it would seem is tweaking even this. Increasingly, it appears that the center of the show is Norman, damaged manchild, Norma, damaged mother, and "Mother," Norman's warped representation of Norma, twisted out of shape by trauma and time.

The relationship between the two is fraught with inappropriate sexual tension that the show leans into at every turn because it's a justifiable choice to make. Norman has seen his mother abused, and he's seen her raped. He understands her to be his only source of unconditional love in this world and is confused and frightened by his own burgeoning sexuality. Norma has harsh opinions about Norman going off with girls, but as previously established, having a son with a tendency to blackout and murder people makes one a bit skittish when it comes to allowing for the occasional date night.

As the series goes on, it becomes increasingly clear how Norma will become "Psycho"'s misunderstood scapegoat. Look only to the way Farmiga is increasingly styled. Season two sees Norma with shorter, often curled and tousled blonde hair and near retro wardrobe, looking more and more like "Psycho"'s doomed pseudo-protagonist Marion Crane. Stalking each frame of the series is a sense of grim inevitability. As with anything born of preexisting material, the audience knows where this story ends up. We know who ends in the swamp and who in the rocking chair. "Bates Motel" is horror not because Norman Bates is an unchecked psychopath but because there's nothing Norma or anyone else can do to keep him from reaching that predetermined destination. The sad truth of the matter is that the downfall of Norma Bates will come not because she was an overbearing, cartoonish representation of sexual repression and misandry but because all of her feverish love and all of her protection will never be enough to heal her broken little boy.