When I saw "Joker" at the Venice Film Festival five years ago, I took extreme and indignant umbrage with it, and I poured out that indignation—some readers thought inappropriately, in a hastily-written review. (I was later informed that I could have taken some time to cool off: a review embargo for the film stood in effect for another five hours after I filed my notice.) Because I did not want to give away plot spoilers, I did not reveal the main source of my indignation.

What set me off was the film's climax, in which Joaquin Phoenix's Arthur Fleck, now gone almost full Joker, appears on a late-night talk show hosted by glib showman Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro). Franklin's object is a mockery of the man in the clown makeup. But Arthur has the last laugh: he pulls out a gun and blows Franklin's brains out on live TV.

This rocked me in a very not-good way. In part because I was fairly confident that this story point was inspired by the 1987 on-air suicide of Pennsylvania political figure R. Budd Dwyer. Footage of him taking his own life was, of course, edited for news reports, but I was at the time enough of a media insider that I was able to watch the unexpurgated footage of the suicide. And to this day, I wish I hadn't. The similarities between the real-life event and what director Todd Philips staged struck me as too specific to be coincidental. I considered what Phillips and Phoenix (and, yes, De Niro) have done to be unforgivably opportunistic nihilism.

So there you have it, in case you were wondering. In my review, I wrote: "In mainstream movies today, ‘dark' is just another flavor. Like ‘edgy,' it's an option you use depending on what market you want to reach. And it is particularly useful when injected into the comic book genre."

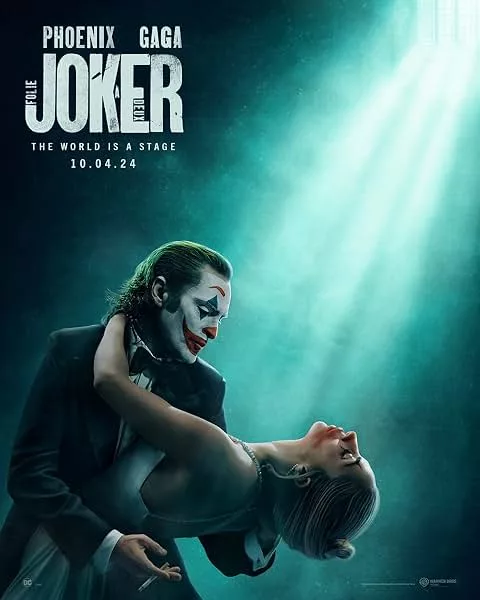

And now I'm back on the Joker beat for the sequel, "Joker: Folie a Deux," which, as you have no doubt heard, is a musical, written and directed, as the first film was, by Todd Phillips. Phillips didn't write the songs, thankfully. This is largely a jukebox musical, with selections from The Great American Songbook ("Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered") and ‘60s international pop ("To Love Somebody," originated by the Bee Gees and further popularized by Janis Joplin) and more. And the best thing I can say about it is that it clearly does not take marketing, as it's conventionally understood, into consideration.

Before assessing the ultimate point of making the second "Joker" picture a musical, we should acknowledge that its rationale is arguably sound. That is, Arthur Fleck, who here makes a severe distinction between himself as a civilian and himself as a "Joker," is a deeply disturbed individual whose warped imagination may well envision his existence as being inside a show of some sort. So, we can concede the filmmakers are acting in good faith by framing this as a musical. Doing so also allows them to slip out of some otherwise desperate straits. The movie is narratively, psychologically, and aesthetically incoherent. Still, it can slide into the first two categories because musicals get away with being narratively and psychologically incoherent just by the nature of their being, you know, musicals.

As it keeps reminding you, the story occurs in the near-immediate aftermath of the repellent murder that capped "Joker." Arthur/Joker is in captivity in one of Arkham's dark, satanic mill-like mental institutions, and in one of his walks to see a visitor, he is practically winked at by a young woman singing in an open room. That's Lady Gaga's Lee Quinzel (DC mavens may be sore that she never goes full Harley Quinn here), and the two soon conspire to see as much of each other as captivity allows before Arthur's trial, which Lee is rather mysteriously accorded sudden citizen status to attend as a spectator. (This is explained sufficiently, if not entirely credibly.) Arthur is smirky and surly when he's not in his Joker makeup, but rest assured, he gets to put it on plenty, either in song fantasies or the trial's reality. And then he goes, well, "Joker."

The trial and the romance are the linchpins of this seemingly endless movie. There are bits—such as Joker's impersonation of a drawling Southern lawyer—that might have been entertaining had they not been positioned in what seems to be the movie's eighth or ninth hour. In the end, the wafer-thin story amounts to the same nihilistic slop that Phillips served up in the first "Joker," albeit remixed, genre-wise.

Some early reviews have complained that the movie doesn't offer much in the way of "Joker Fan Service." This makes me laugh a bit; I understand that the character is indeed a pop culture phenomenon and indeed fictional, but when you consider just what he's about, what exactly would "Joker Fan Service" entail? You might as well talk about "Charles Manson Fan Service." It certainly is a sick and additionally twisted world in which we live.

The only other aspect of the movie I can wax positive about aside from its indifference to whatever audience it might attract is that of performance. Both Lady Gaga and Phoenix clearly put a lot of work into their characterizations and interactions. The different performance modes they use in singing, for instance, low-key and fallible in their own "real lives," full-on, professional quality belting in their shared dreams. While Gaga maintains well for the duration of the picture, Phoenix's virtuosity eventually curdles into narcissistic exhibitionism (his ostensible Joker "dance" really just looks like he's doing pre-Yoga stretches). But it's still virtuosity, for whatever it's worth.