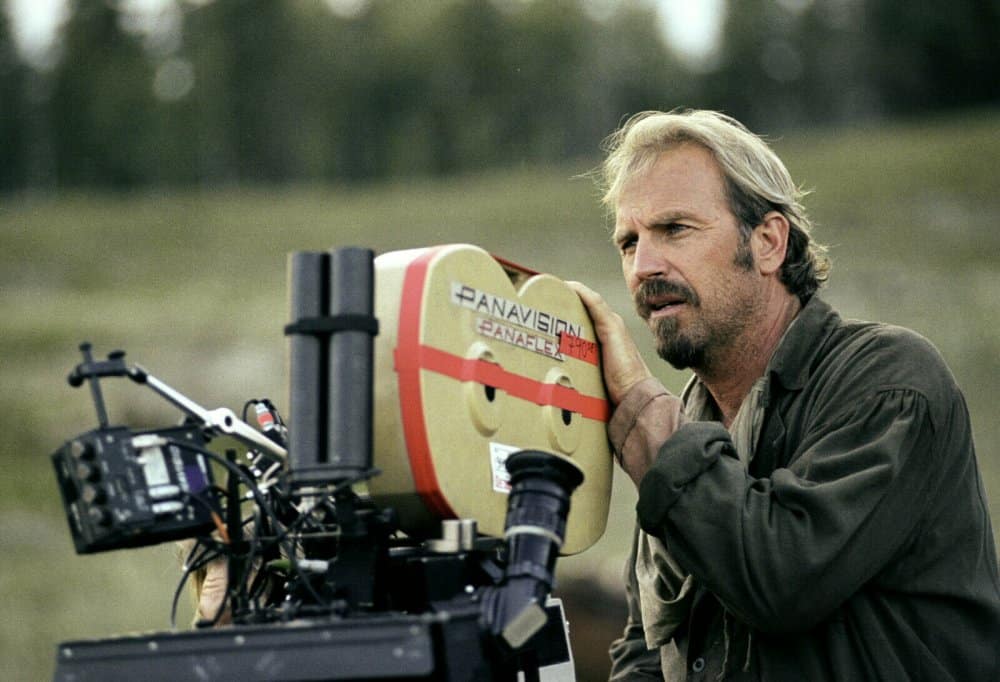

If you're an animal in a movie Kevin Costner directs, I have bad news: You may not be long for this world. It's a habit of the Oscar-winning filmmaker that his heroes regularly befriend a loyal creature—a horse, a dog, a wolf—forming a bond that, sometimes, is the closest relationship these solitary characters have. Don't get too attached to those critters, though, because invariably they will be killed—usually by the movie's most reprehensible villains.

In preparation for this weekend's "Horizon," Costner's ambitious first installment of a multi-film Western he's developing, I rewatched the three movies Costner directed beforehand—"Dances With Wolves," "The Postman," "Open Range"—and I was struck by his tendency to have his characters' beloved animals bite the big one. I think it says something about him as a filmmaker—his willingness to go for the emotional jugular, his need to see the world as divided between the decent and the wicked. For Costner, animals represent what is most wild, free and pure—their openhearted, innocent spirit worthy of emulating. It's no accident those animals die.

From the start of his fame, Costner has made no apologies about his earnest, everyman demeanor. Sure, he had swagger in "Bull Durham," but in films like "The Untouchables," "Field of Dreams" and "JFK," he played men who were slightly square. They weren't cool, but they weren't trying to be—they were duty-bound to do something greater than themselves. His characters are often mocked or misunderstood, but others' opinions don't matter to Costner's men—they're on a mission, and they approach it with an unwavering zeal.

Does that make them heroic or corny? Timeless or hopelessly out-of-touch? What has made Costner such a fascinating figure is how he embodies those tensions, leaving viewers to fight amongst themselves over what his image means. I've never interviewed Costner, never crossed paths with him, so I have no idea how much his real self overlaps with his onscreen persona. I'm only judging the work. But when he turned his attention to directing in the late 1980s, his stardom on the rise, he helmed movies that streamlined his essence into their base elements. Those films have not always been good, but as I await "Horizon," I think they're his most representative. They allow him to let his cornball-flag fly.

"Dances With Wolves," "The Postman" and "Open Range" are all Westerns. In them, he rides a horse, looks out at the horizon, pondering the grandeur of the natural world. He is looking for something ineffable, or maybe he's trying to escape the life he once led. The orchestral score swells in the background—he may seem like an ordinary man, but he will be called upon to do extraordinary things. He will meet the moment—after all, it's what any honorable person would do in the same situation.

The best of his three directorial efforts remains "Dances With Wolves," which won seven Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. It is perhaps now best-remembered as the film that beat out "Goodfellas," with many complaining at the time (and now) what a travesty that was. Based on the novel by Michael Blake, who wrote the screenplay, "Dances With Wolves" is not as great as that Martin Scorsese classic, but it remains a completely respectable, frequently affecting drama about a Union soldier, John J. Dunbar, who wants to die at the start of the film and ends up being reborn on the vanishing frontier, befriending the Sioux people and falling in love with a white woman (Mary McDonnell) who was adopted by the tribe when she was just a baby. John is a good man tired of war, and he finds in the Sioux a kinder, more thoughtful community than the one from which he came. As he is given a Sioux name, Dances With Wolves, he becomes the person for whom he'd always been searching inside himself.

Plenty sneered at the film's liberal pieties. (I always love to quote New Yorker critic Pauline Kael's derisive dismissal: "Costner has feathers in his hair and feathers in his head.") But where other message movies curdle over time, their stridency and self-righteousness becoming dated, "Dances With Wolves" still feels properly respectful of the Indigenous people it seeks to understand. The film benefits from Costner's shy charm and aw-shucks humility, his unassuming public persona nicely dovetailing with the movie's unfailing modesty. (This might be the least self-important and lumbering three-hour epic.) That a copy of "Dances With Wolves" appears in the home of a character in "Fancy Dance," the recent Indigenous drama made by and starring Indigenous actors, speaks to the movie's continued relevance in the communities that Costner wanted to honor. ("‘Dances with Wolves' was the kind of movie that we would watch over and over as kids," "Fancy Dance" director Erica Tremblay said, with star Lily Gladstone adding, "It was a new revisionist Western that was different. It was the first time you see Lakota language spoken intimately.")

Every once in a while in his film career, Costner has played villains. But when he directs, his character is, reliably, good. They are never heartless bastards who change their ways—at worst, they've made some mistakes, but we never doubt their core decency. With "Dances With Wolves," his potentially simplistic character felt stirring because Costner was so locked-in as a modern-day Jimmy Stewart or Gary Cooper—a symbol of soft-spoken American dignity—that his straightforward swellness felt like solace amidst a world of cynicism and despair. Costner made those clichés feel real, and we loved him for it.

But that quiet decency began to grow rickety by the time he returned to the director's chair seven years later for "The Postman." In between, he had starred in "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves" and "Waterworld," one a hit (but not well-reviewed) and the other not a hit (and largely ridiculed because of its ballooning budget and rumored on-set issues). The Costner of the mid-1990s seemed a little more strained, the appealing everyman starting to come across as one-note. When "The Postman" arrived on Christmas in 1997, his onscreen heroism felt like shtick, the easy charm giving way to a more self-conscious, self-admiring false modesty. Suddenly, his genuineness seemed disingenuous.

With "The Postman," Costner aspired to do Frank Capra, arguably America's all-time finest cornball director, in the guise of a post-apocalyptic road movie. He played an unnamed nobody wandering the wastelands of the United States who stumbles upon a dead postman, putting on the deceased's uniform and pretending to be a letter-carrier who, in short order, is mistaken for a leader because he offers hope to the disillusioned masses trying to survive in a devastated country.

If "Dances With Wolves" was Costner's paean to Indigenous peoples, "The Postman" was his plea to restore America's luster—and not in the Donald Trump/MAGA way. For all the film's many failings—its convoluted plot, its threadbare production values, the fact that it goes on forever—what is both endearing and dopey about "The Postman" is Costner's fervent belief that he's sounding the alarm about his country's imminent collapse into tyranny. His view of America is one in which good people do good things for others—a vision of the nation as sepia-toned, nostalgic and nonexistent as anything espoused in "Field of Dreams." But what ultimately kills the film is its maker's insistence that the unnamed loner become a Heroic Figure, one deserving of being immortalized as a statue after his death so future generations can look upon him in awe. I'm not speaking metaphorically: That is precisely what happens at the end of "The Postman," a movie about making both America and Costner great again.

After the commercial and critical failure of "The Postman," Costner's career nose-dived: The soggy romantic drama "Message in a Bottle" was a hit, but "For Love of the Game," "Thirteen Days," "3000 Miles to Graceland" and "Dragonfly" all tanked. Still, Costner the director soldiered on, making 2003's "Open Range," the most understated of Westerns that seemed to be a conscious course correction after "The Postman's" foolhardy ambition. Old-fashioned to the nth degree, with Costner's loyal cattleman Charley the sidekick to Robert Duvall's gritty Boss, "Open Range" felt designed to remind audiences of the Costner they used to like—the no-big-deal star not putting on airs or playing a goofy waterlogged action hero with gills. The film connected with viewers and got good reviews, but that didn't mean he tempered his most Costner-y qualities. Still hokey, still hopelessly in love with a vague notion of bygone decency, Costner turned "Open Range" into a tribute to doing the right thing—a salute to the few plucky individuals willing to stand up to the wicked.

Set in the 1880s, only about 20 years after "Dances With Wolves," "Open Range" finds Boss and Charley enjoying a productive life as long-in-the-tooth open-rangers—that is, until they run afoul of a ruthless, powerful rancher (Michael Gambon) who wants them gone, killing (among others) their trusty dog. As anyone familiar with Costner's oeuvre knows, once his character's favorite pet is offed, that's when it's clear evil is in our midst. Falling in love with a local woman, Sue (Annette Bening), but still haunted by his murderous past—he did some Bad Things during the Civil War—Charley ultimately confronts the rancher in a violent showdown, the big square-off both a final stand and one last shot at redemption. For Costner, it's not just about good guys and bad guys—it's about restoring the moral order.

Costner has made Westerns that he didn't direct—"Silverado," "Wyatt Earp," "Yellowstone"—and it's easy to see why he finds the genre so seductive. Even the most revisionist Westerns acknowledge an unimpeachable code of ethics that governs all behavior—and the importance of meting out punishment to those who step out of line. Much like the sacrificed animals in Costner's movies, Westerns elicit a sentimental connection to a world of freedom and individuality that resists being tamed by modernity. Even when Costner set "The Postman" in the near-future, he envisioned a universe in which a man on a horse could inspire the populace. And there's no question that he looks dashing astride those noble beasts—although, it's worth noting he's a less aggressively masculine version of the John Waynes of yesteryear. He's the best of both worlds: the sensitive cowboy.

That sensitivity has been the hallmark of his directorial efforts—even in "The Postman," he shows off his softer side—but it's especially apparent in "Open Range," which like so many Westerns is about the passage of time. But it also examines growing old and wondering what you've done with your life. The film is his gentler, less self-critical version of "Unforgiven" in which the aging gunman reckons with his past—although in "Open Range," the sobering aftermath never comes, replaced by the touching potential blossoming of Charley and Sue's love affair. There is no sense of a world whose encroaching darkness draws ever nearer—Costner kills the villains and gets the girl and then heads for the nearest sunset. Sometimes, being corny means selling the fantasy. It means leaving all the more troubling aspects of life out of the frame.

Not that Costner is incapable of emotional nuance: "Dances With Wolves" ends on a melancholy note, his character forced to ride off away from the tribe in order to save it, a selfless act that will be in vain. (The Sioux eventually are captured by U.S. forces.) With each passing year, "Dances With Wolves'" innocent, uncomplicated sincerity remains its strongest feature. Costner never condescends to the Native American characters, never reduces them to cutesy or oh-so-wise abstractions. He's so genuinely humble in telling other peoples' story that it doesn't rankle like so many other white artists' films do. Costner's corniness was his saving grace because it was so deeply him. Watch his later films, and that tendency is still there, but it's occasionally undercut by success, ego and misplaced confidence.

Even Costner's best stints behind the camera can be fatally eye-roll-y—he was cringe before that was a thing. But as a result, it's hard not to have affection for his directorial career. There's no one else working in his register—no one so wide-eyed and golly-gee in pinning his faith on our inherent goodness. Maybe "Horizon" will be a debacle. (The initial reviews lead me to think so.) But I don't doubt for a moment that Kevin Costner has invested every ounce of himself in every single minute of its three-hour runtime—not to mention every single minute of the future installments to come. The guy doesn't operate in half-measures—he doesn't phone in anything. His genius is appealing to the mawkish, cheesy, corny and decent in all of us. He sells us a dream we're too cynical or wise to believe in ourselves—but much of the time, he's talented enough to make us wish we could