This review originally ran on January 10th and is being re-run because it's now on Amazon Prime.

Ladj Ly's "Les Misérables" is haunted by the memory of the fall of 2005, when riots broke out in the suburbs of Paris (and other cities), riots which raged for three terrible weeks. The mostly North African immigrant population in these suburbs were protesting the constant police harassment as well as the tragic death of two kids, electrocuted while hiding from the police in a substation. "Les Misérables" takes place in 2018, but "2005" is never far from anyone's consciousness. "Ever since 2005..." one character says. Nothing more needs to said. Everyone understands. Nothing has been solved or addressed. If anything, the situation is even more damaged and polarized. "Les Misérables" is a gripping experience, tense and upsetting, showing how seemingly small events, perhaps manageable in the particulars, can balloon into something out of control, like a fire exploding into a conflagration.

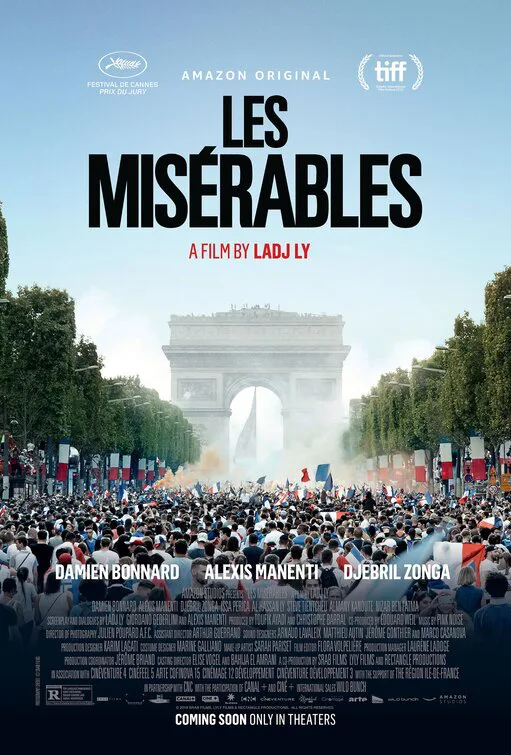

The opening scenes take place during the World Cup celebrations in 2018, showing a group of kids joining the giant crowds cheering on the streets of Paris, after jumping turnstiles to get there. They drape themselves in the French flag, join in the singing of "La Marseillaise," and are shown celebrating in epic shots backgrounded by familiar Paris landmarks, the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower. Ly tosses you into the middle of the crowd, pressing in on all sides in seething exhilaration and unity of purpose. This sequence is a prologue, unconnected to the events that follow, at least in terms of plot, but crucial in establishing the concerns and themes of the film. As "Les Misérables" unfolds, these same kids, living in a housing project in Montfermeil, are targeted by the police for what is, essentially, a prank, and events will come to an uncontrollable boil, egged on by the racist commando-style of the police, and the general unrest and paranoia already simmering in the area. But first, Ly shows the kids joining in the celebration for France. It's their country, too.

"Les Misérables" then shifts its focus to a small police team, patrolling the streets of the suburb of Montfermeil, with its mainly North African population. There are two veterans of the detail: Gwada (Djebril Zonga), who grew up in the area, is bilingual (French and Berber), and is able to diffuse tensions, and Chris (Alexis Manenti), Gwada's polar opposite, a white Frenchman whose theory of policing is simple: "Never sorry. Always right." On this one very long day, they have a new guy with them, Corporal Ruiz (Damien Bonnard), whom they nickname "Greaser" because of his slicked back hair. Ruiz is a newbie, whose main experience has been as a first responder (this experience will come into play later), and learning the ropes is not easy. Montfermeil, famously, is where Victor Hugo placed the Thenardier's inn in his 1862 magnum opus: Chris jokes that "Gavroche" would now be "Gavrochah," meaning Muslim, presumably.

There are interactions throughout the day with civilians, some good-natured, some hostile. Chris is a live wire, Gwada more calm, while Ruiz just learns the lay of the land. There are many players on the board, and the narrative leaps around, from the kids seen in the opening, to the cops, to the Mayor, to the Muslim Brotherhood (who try to keep the kids under control at the mosque), to an "ex-thug" (so-called) who has turned himself into the spiritual leader, the "go-to guy" of the area. All of these alliances shift and transform, depending on the context.

It's all just a normal day until a stolen lion cub threatens to turn 2018 into 2005 all over again. The circus "gypsies" show up en masse demanding the return of their circus lion, and the confrontation is so violent the cops can barely contain it. What could be handled with a simple command to the teenage perpetrator—"Hey, kid, just return the lion, okay?"—is a situation completely blown out of proportion, and in the high-adrenaline atmosphere of hyped-up cops and furious teenagers, anything can happen, and anything does. One added layer of complication is that the confrontation is caught on the drone camera, operated by a solitary kid on the roof.

The comparison with "Do the Right Thing" is apt (the condensed timeline, the multi-character story, the "inciting event" of police violence followed by justifiable outrage), and Ly juggles multiple balls deftly. This is a three-dimensional portrait of a community, its striations of authority, the wary alliances made, the backdoor deals, the wheeling and dealing between unlikely allies. Ly uses a documentary style, but maintains control over extremely complicated chase sequences and fight sequences. The potential of violence trembles in every interaction, but Ly doesn't pump things up artificially. The subject is heated enough, it needs no over-heating.

In 2010, far-right politician Marine Le Pen commented on the plan to close off the streets in a Paris neighborhood to make room for Muslim prayers, referring to it as an "occupation," like in wartime: "There are of course no tanks, there are no soldiers, but it is nevertheless an occupation and it weighs heavily on local residents." What is at stake in "Les Misérables" is not just a stolen lion cub, or even the fate of this one neighborhood. What is at stake is issues of citizenship, which really means issues of belonging. Who "gets to" belong? Who "gets to" think of themselves as "French"? The cops make it perfectly clear in their behavior that the people outside their car windows are not really "French" to them.

The opening scenes, where the kids celebrate the World Cup in front of the Eiffel Tower, linger and haunt, increasingly painful in memory.