In the year 2020 which marks the centennial of the passage of the 19th amendment guaranteeing a woman's right to vote, no one is more relevant to write about during Women Writers Week than the writer who revolutionized the fight for women's rights over a half century ago: Gloria Steinem. She began as a writer, and like her pioneering journalist mother before her, writing—as a woman—was an uphill battle.

She first had to break down the boundaries of what her male bosses considered appropriate for a woman to write about: food, fashion, family. Steinem made her mark and her point of view clear in a two-part article for Show Magazine called "A Bunny's Tale" in 1963 when she went undercover as a Playboy bunny. Her bosses loved it, even though Steinem's goal was more subversive than they'd imagined.

Beneath the inside scoop on what "bunnies" stuffed in their bustiers as cleavage enhancers, Steinem revealed the women's underpaid, overlong shifts, and the humiliation of their having to undergo internal exams in order to qualify for jobs serving drinks. It sold a lot of copies, and underscored the systemic objectification of women as sex objects. Eventually, Steinem would help found a magazine devoted to real women's issues—called Ms. Magazine back when folks made fun of the marriage-neutral prefix that is now standard.

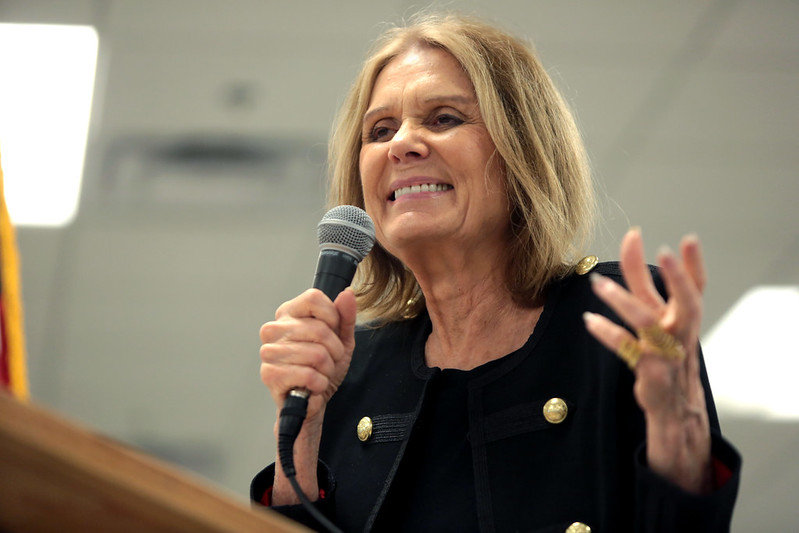

Terrified of public speaking, Steinem's natural outlets were non-verbal: writing, dancing. But by the time I first heard her in person, Steinem had become the voice of the second wave of feminism. Speaking out from behind aviator glasses and long hair, she had thrown herself into the arena and bravely called out inequities that went well beyond a woman's right to vote. She incurred the public wrath of presidents and Harvard College professors, male news anchors and talk show hosts, and conservative female activists like Phyllis Schlafly who shamed her for not being married or having children.

What Gloria Steinem said to me that day almost 50 years ago, shaped my idea of the world and my place in it. It happened when I was about 18 years old. I had been hearing about "women's lib." I distinctly remember thinking, "Why do I need that? I can do anything I want!" Or maybe not. Maybe doors that I hadn't even tried to open yet were closed.

I heard that Steinem was coming to Boston to speak for free at the Ford Hall Forum and decided to go and hear for myself what she had to say. After her speech, I raced down to the stage, and with a carefully prepared question in mind, I worked my way through the crowd. When I got within shouting distance, I managed to blurt out, "Ms. Steinem, I go to Simmons College, a girl's school"—and she stopped me dead in my tracks. In front of everyone, looking me straight in the eye, she said in that level, uninflected voice, "You don't go to a girl's school. You go to a women's college."

I don't remember anything after that—neither my question, nor her answer. I only remember the shock of that moment, that sudden realization of an unconscious bias I was holding about myself, a diminished sense of "me" that I had somehow absorbed. I eventually understood that it wasn't just the world outside that women had to take on, but our own inner world infected by the pandemic of patriarchy. The world seemed to expand instantly, along with my place in it. It was the first question I ever asked as a would-be reporter, and I went on to become a journalist myself.

This year, almost 50 years after our first encounter, I met Gloria Steinem again on the opening night of a new play by Emily Mann at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, MA called Gloria: A Life. The play's second act takes the form of a talking circle with the whole audience, as inspired by the women's talking circles Gloria had witnessed as a young student traveling through villages in India. I shared my story in the circle and the conversation that opened up was funny, moving, honest. Everyone was included—whoever we were in that moment, however our experience had led us there.

Gloria has always recognized that women's power comes not from hierarchy, but from circles, not from "ranking" but from "linking." Not from one voice, but from many, different voices. Gloria was never exclusive but deeply inclusive. From the beginning Steinem says she "learned feminism disproportionately from black women," and women like civil rights activist Florynce Kennedy, and Wilma Mankiller first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Today we call that inclusion and diversity, and the conversation is intergenerational, interracial, intersectional. This is what the women's movement at its heart has always been, a movement that moves more than women. It's a cry for justice across all borders in an angry, polarized era when the struggle between those with and without power is coming to a head, when those demonized as "other," from immigrants to who is fit to be president, is hotly contested. This movement, and Steinem's abidingly humane sensibility, is the most foundational, radical, and inclusive vision of our time.

In the fallout of the Trumpocalypse, Steinem has also inspired a new film by Tony Award-winning writer, director, and filmmaker Julie Taymor. Based on Steinem's autobiography My Life on the Road, Taymor's movie premiered this January at the Sundance Film Festival and is due out this fall. It's called "The Glorias" and stars different actresses playing Gloria at various and intersecting stages of her life, among them, Alicia Vikander as the younger Gloria, and Julianne Moore as the older and wiser. We also get a glimpse of Gloria as child and the parents who shaped her, and a surreal picture emerges: "Gloria" as an integrated consciousness. She talks to herself across time, and to our time when the injustices that she tackled more than a half century ago remain stubbornly entrenched—equal pay for equal work, sovereignty over one's own body, systemic sexual harassment surfacing in the #MeToo movement.

Now at age 85, Steinem remains on the front lines—writing, speaking, marching. Her energy continues to mobilize millions of women, many running for office in record numbers. She stands on the shoulders of the women before her who fought and won the right to vote 100 years ago, who themselves stood on the shoulders of activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1848 who birthed the women's movement at the first American convention for gender equality at Seneca Falls, where Steinem circled back in 1993 and was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

And she tells us this is only the beginning. In 2014, in an article she wrote for Ms. Magazine, Steinem explained "Why our revolution has just begun":

"At my age, in this still hierarchical time, people often ask me if I'm ‘passing the torch.' I explain that I'm keeping my torch, thank you very much—and I'm using it to light the torches of others. Because only if each of us has a torch will there be enough light."

That night when I told my story and thanked "Ms. Steinem" for lighting a fire in that "girl's school" dropout, she once again stopped me in my tracks and said, "Please. Call me Gloria."

Header photo courtesy of Gage Skidmore.