All of the characters in Tim Kirkman's "Loggerheads" are good people, by their own lights. The lights of some people allow them to be content, while the lights of others fill them with sadness and regret. Sometimes you can move from one group to another. Not always.

The story involves the years 1990 and 1991 and three areas of North Carolina: Asheville, Eden, and Kure Beach. The characters are dealing in one way or another with homosexuality and adoption. One of the characters provides a connecting link involving the others. That makes it sounds like things are all figured out, but "Loggerheads" is not a movie where the emotions are tidy and the messages are clear. It is about people trying to deal with the situations they have landed in.

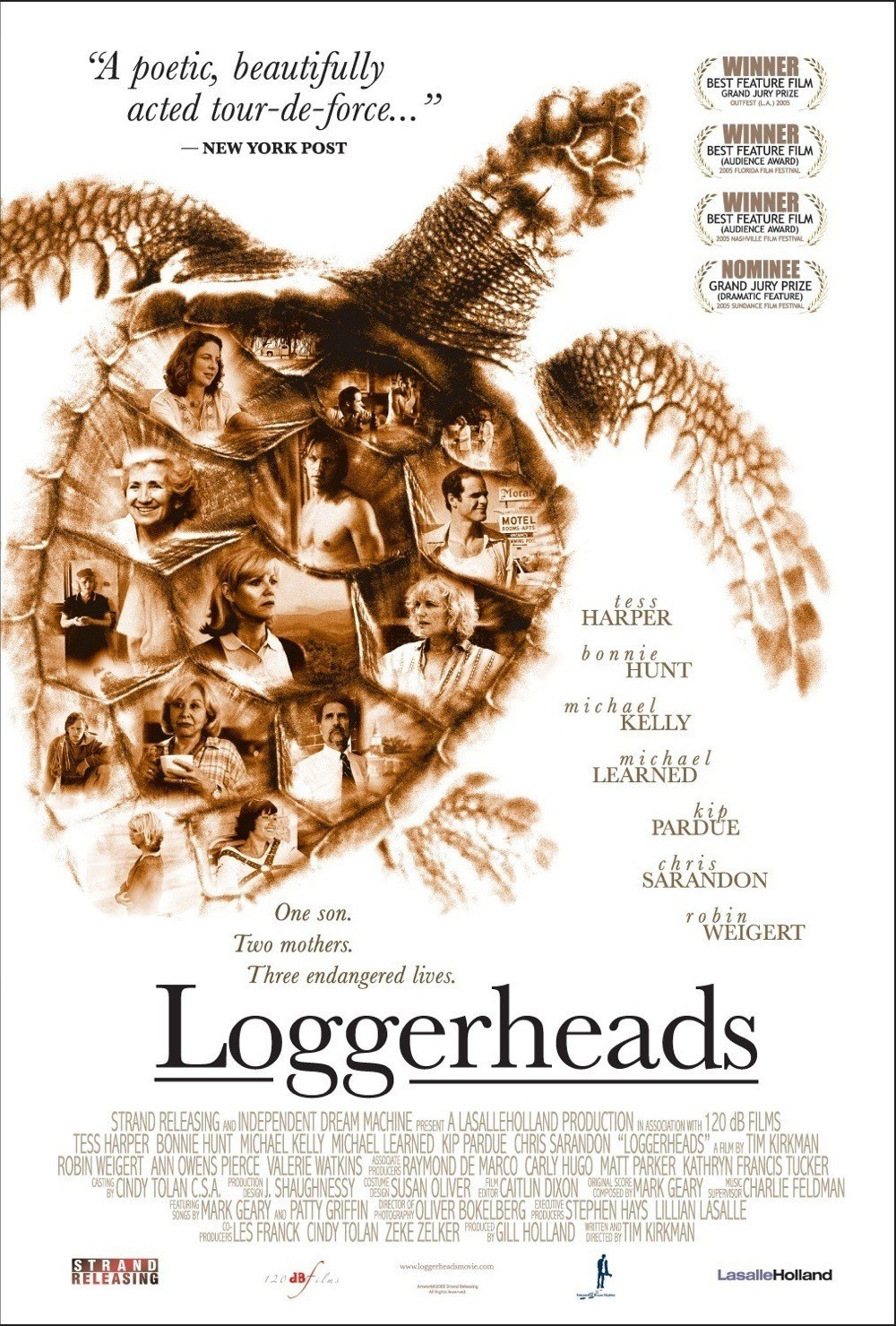

We meet a woman named Grace (Bonnie Hunt) who works behind a rental-car counter, and has moved back to Asheville to live with her mother Sheridan (Michael Learned). In Eden, we meet a pastor named Robert (Chris Sarandon) and his wife Elizabeth (Tess Harper). On Kure Beach, George (Michael Kelly) runs a shabby motel, and Mark (Kip Pardue) sleeps on the beach and observes the nocturnal behavior of loggerhead turtles. Loggerheads always return to the place where they were born, and that is something not everyone in the movie finds it easy to do.

I want to go slow in describing the plot, because its developments unfold according to the needs of the characters. The movie is not about springing surprises on us, but about showing these people in a process of discovery. The performances are not pitched toward melodrama; the actors all find the right notes and rhythms for scenes in which life goes on and everything need not be solved in three lines of dialogue.

George and Mark, for example, sense easily that they are both gay, but become more friends than lovers. The pastor and his wife had a son they have not seen since he was 17, and they observe that among their friends and neighborhoods, "nobody ever asks about him." Grace gave up a child for adoption when she was 17, and now wants to find that child, but in North Carolina an "anonymous" adoption cannot be undone.

These characters are not extreme examples of their type. The pastor is not a religious extremist but has ordinary conservative values. Here's how that works: When a new family moves in across the street, Robert suggests to Elizabeth that she ask them to come to church on Sunday. Then she informs him "there is no woman in that house," and she thinks they're a gay couple. "Should I invite them to church?" she asks. Her husband says, "Let's just wait and see if they come on their own."

Elizabeth is much distracted by her longtime neighbor Ruth (Ann Pierce), who has placed an anatomically complete reproduction of Michelangelo's David on her front lawn. "If it were the Venus de Milo," Ruth says, "you wouldn't hear a peep out of anybody." Elizabeth suggests she put the statue in the backyard, so the neighbors won't have to look at it. "That's your solution to everything," Ruth says. "Move it to the backyard."

On Kure Beach, George gives Mark a room to stay in, and Mark thinks this may involve a "barter arrangement," but no, George is just doing him a favor. Unlike many gay men in movies, these two characters are not as concerned with sex as with their life choices; in different ways, both choose to live on the beach, and are content to be far from the action. They talk about matters of life and death, George often seated comfortably, Mark usually standing or pacing, smoking.

In Asheville, Grace and Sheridan have issues going back to the day the mother insisted that her pregnant daughter give the baby up for adoption. "I was just trying to do what was best for everyone involved," she says in her defense. "I know you were," says Grace, and she does, however much she wanted to keep the baby, and however empty the rest of her life has become.

Events now happen to these people which I will not describe. They bring some happiness, some sadness, some closure. It is Elizabeth, the pastor's wife, who moves most decisively to put her life in line with her feelings. Curiously, we are by no means sure that her husband Robert will not someday follow her in that direction.

These people are not robots programmed by the requirements of the plot. They want to be happy, and they want to feel they are doing the right thing. One of the characters, in my opinion, does the wrong thing, but thinks it's the right thing. Sad, but there you are. "Loggerheads" offers these hopes: That our understanding of happiness can encompass more possibilities as we grow older. And that to find that happiness, we will have to do what we decide is the right thing, and not what someone else has decided for us.