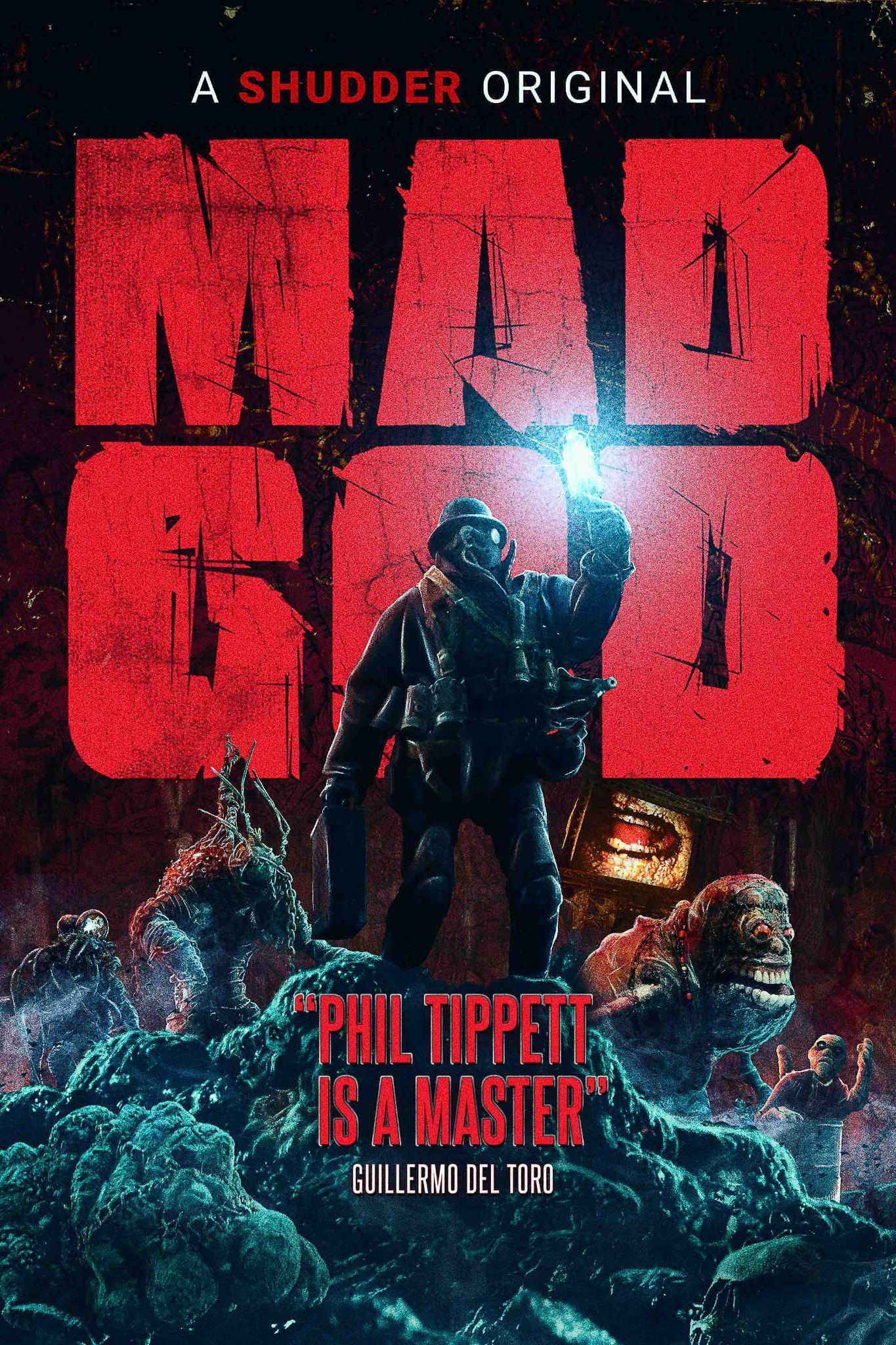

How does one describe "Mad God," the stop-motion animated fantasy that took writer/director and special effects innovator Phil Tippett about 30 years to complete? "Mad God" doesn't really have a conventional plot. More like there are a handful of characters, including the Assassin (credited to three voice actors), the Surgeon (two voice actors), the Alchemist (three), and the Last Human (just British punk filmmaker Alex Cox). And they're all either at cross purposes or looking for a way out. Imagine, if you will, a dystopian nightmare set in a post-industrialized world that's forever teetering on its last legs, but never quite falls over.

This description does not, admittedly, tell you much, but the movie's less of a narrative-driven parable than a dazzling and corrosively cynical vision of a hyper-compartmentalized society that's struggling to both die and reset. Tippett's overwhelming descent into his own id also inevitably reveals itself to be about its own miraculous creation. Beautiful and disgusting, mean and awe-inspiring, "Mad God" looks like multiple people died to make it exactly as you see it.

"Mad God" is a microcosm of amoral scavengers who keep their motives to themselves and are always seconds away from being devoured and/or repurposed by the next derangoid to come along. First there's the Assassin, a humanoid soldier who, clad in a gas mask and steampunk-style suit of iron-clad armor, travels to a base of ticking suitcases to plant an explosive that never detonates. He's guided by a treasure map that flakes apart in his hands as he tiptoes around giant monsters and feature-less homunculi. Everybody gets flattened, dismembered, or otherwise pulverized, sometimes for food, sometimes because they're in the way of oncoming traffic.

The Assassin's story soon gives way to a competing subplot involving the Surgeon, the Nurse (Niketa Roman), and a tentacle-shaped monster who looks like the "Eraserhead" baby after it hit puberty (hard). Then there's another story involving Cox's Last Human, who sends a different Assassin on another trip, guided by a new and slimy map that's stitched together by a trio of witches that the Last Human keeps under his desk. Everybody's looking for something, but it's often hard to tell what until they either find it or just set the next domino in motion.

Many people will and maybe should watch "Mad God" for how it looks. This is, after all, a movie that announces what it's about through its production design and densely layered soundtrack. Animated figurines made of slime and mulch trundle around a dynamically shot and compulsively arranged collection of model sets that either pay explicit homage to or would sit comfortably besides the stop-motion wonders of pioneering animators Ray Harryhausen, Willis Harold O'Brien, and Jan Švankmajer. It's amazing that this movie exists, is what I'm trying to say.

That said: Tippett's characters do act in ways that, by sheer juxtaposition, conform to character-revealing patterns behavior. Hoodoo-doll style peoploids stumble around each other, either to complete their slave labor-style tasks or to forcibly take what they want. Everybody turns a blind eye to survive. In some scenes, characters either seem to enjoy or simply accept the daily reality of being surveyed. In all scenes, there's a melancholic certainty that whatever comes next won't be friendly or necessarily sensible beyond its basic self-serving function: as long as I can get mine, everyone/thing else can go to hell.

"Mad God" is like a Rabelaisian protest against modern society, which is only weird if you think of the present as a unique moment divorced from the history of our hopelessly polarized, war-ravaged, and ruinously self-absorbed society. There's no clear signposts of our specific present day—though if you squint, you may spot Putin and Trump dry-humping each other?—as you might imagine given how long it took to make "Mad God." But there are plenty of signs that Tippett's movie is, at heart, about how life senselessly persists despite its barbaric conditions and prevailing death-drive.

Tippett's film is also really funny in a juvenile sort of way, since everybody's a second away from being squashed by a giant Gilliam-esque foot. The Assassin carries one of many explosives while the Alchemist wants to create a new world that, as we see in a prophetic montage, will probably develop and then collapse. Everybody's fair game because we're all subject to the same gory and gross terms and conditions.

I don't know how Tippett and his collaborators managed it, but "Mad God" feels like a movie that exists in spite of the general working conditions of modern filmmaking. Rather than rush through a hasty exercise in formal experimentation, Tippett and the gang have made the kind of fantasy that too often seems to exist in the magical realm of unproduced dream projects, like Alejandro Jodorowsky's "Dune" and George Lucas' home movies. "Mad God" may not be to everyone's tastes, but it's going to outlast most of us anyway.

Available in select theaters on June 10, and premiering on Shudder on June 16.