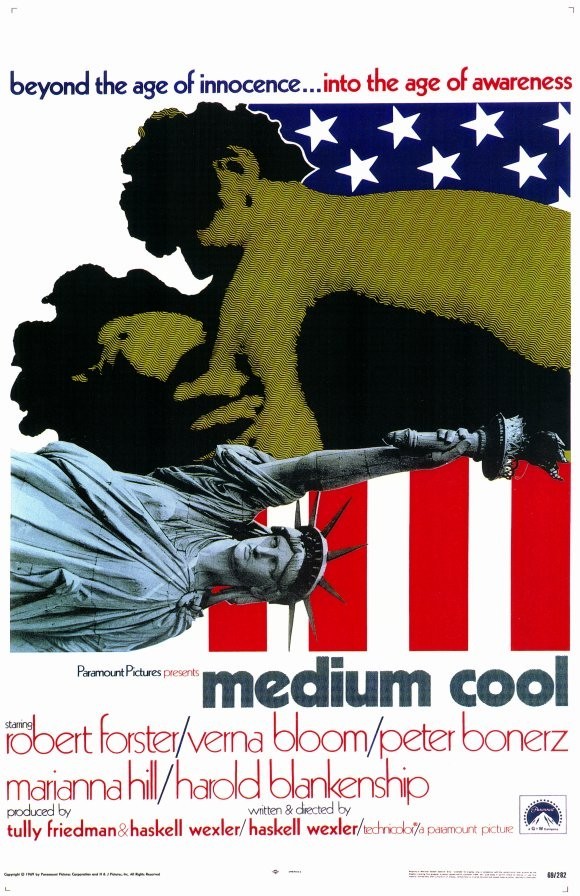

I don't think I exactly want to review Haskell Wexler's "Medium Cool." A formal review (or even my chaotic version of one) would be inappropriate to this most informal and direct of films. What is needed is a response and some speculation.

Besides, you already know pretty much what "Medium Cool" is about. We had a long interview with Wexler six weeks ago in The Sun-Times. The national magazines are full of photos of his characters: the TV cameraman, his sidekick, his girl and her remarkable 12-year-old son. And by this stage of the game, you don't want to read another rehash. So instead, I'd like to discuss the form of "Medium Cool." That is, the way the movie was conceived, shot and edited.

Five years ago, this film would have been considered incomprehensible to the general movie audience. Now it's going into a big first-run house, and you don't hear the Loop exhibitors talking so scornfully about "art films" anymore. So what's going on when an experimental, radical film like "Medium Cool" can get this sort of exposure?

What's happened, I think, is that moviemakers have at last figured out how bright the average moviegoer is. By that I don't mean they're making more "intelligent" pictures. I mean they understand how quickly we can catch onto things.

Even five years ago, most Hollywood movies insisted on stopping at B on their way from A to C. Directors were driven by a fierce compulsion to explain how the characters got out of that train and up to the top of the mountain. And so, their movies crept along slowly, and we spent so much time climbing the mountain that we didn't give a damn what happened when we finally got there.

But a movie named "The Graduate" didn't bother with that. For years, underground and experimental films had stopped using the in-between steps. But now, here was one of the biggest commercial movies of all time, and when Benjamin plunged onto the prone form of Mrs. Robinson, there was a cut in mid-action to Benjamin landing belly-down on a rubber raft in a swimming pool. And no one had to explain why Mrs. Robinson turned into a raft, or how Benjamin got into the pool.

Most of us are so conditioned by the quick-cutting and free association of ideas in TV commercials that we think faster than feature-length movies can move. We understand cinematic shorthand. And we like movies that give us credit for our wit. We didn't like "Shoes of the Fisherman," no matter how noble its intentions, because it insisted on explaining everything. We liked "Bullitt" because it moved at our speed.

And "Bullitt," to grab a recent example, did something else. In all movies, from Bogart to James Bond, symbols meant what they were. Bogart got into a souped-up Buick Special and Bond got into an Aston-Martin, and it was the car's prestige that was important. But in fact, the cars mostly sat there being Buicks and Aston-Martins.

"Bullitt" distilled the power of the car symbol. The "Bullitt" chase was not about what a Mustang and a Charger were -- but about what they did. And it was the doing, the action, the speed, that exploited the cars as symbols of Power.

A third example and I'm through.

All of us are capable of switching on the TV Late Show at any point during the movie, and figuring out for ourselves what's going on. The other night, I turned on a John Wayne sea epic. In the first 30 seconds, John Wayne had given orders to burn the lifeboats for fuel and had sternly ordered a girl to stay off the bridge in time of crisis.

From these two events, it was possible to theorize that the movie was (a) about an endangered mission, most likely undertaken for a crucial purpose -- else why the fuel shortage? -- and (b) had a romantic subplot that probably involved Wayne's delayed realization that he loved the girl.

I made these brilliant deductions on the basis of having seen countless other Grade B movies, and on a familiarity with the basic John Wayne character. Another 30 seconds probably would have revealed where the ship was headed, and why. If I'd held out 15 minutes, I probably would have gotten to see Wayne kiss the girl.

Conventional movie plots telegraph themselves because we know all the basic genres and typical characters. Haskell Wexler's "Medium Cool" is one of several new movies that knows these things about the movie audience (others include "The Rain People," "Easy Rider," "Alice's Restaurant," etc.). Of the group, "Medium Cool" is probably the best. That may be because Wexler, for most of his career, has been a very good cinematographer, and so he's trained to see a movie in terms of its images, not its dialog and story.

In "Medium Cool," Wexler forges back and forth through several levels. There is a fictional story about the TV cameraman, his romance, his job, his girl and her son. There is also documentary footage about the riots during the Democratic convention. There is a series of set-up situations that pretend to be real (women taking marksmanship practice, the TV crew confronting black militants). There are fictional characters in real situations (the girl searching for her son in Grant Park). There are real characters in fictional situations (the real boy, playing a boy, expressing his real interest in pigeons).

The mistake would be to separate the real things from the fictional. They are all significant in exactly the same way. The National Guard troops are no more real than the love scene, or the melodramatic accident that ends the film. All the images have meaning because of the way they are associated with each other.

And "Medium Cool" also does the second thing -- sees not the symbols but their function.

Wexler doesn't see the hippie kids in Grant Park as hippie kids. He doesn't see the clothes or the life style, and he doesn't hear the words. He sees their function; they are there, entirely because the National Guard is there, and vice versa.

Both sides have a function only when they confront each other. Without the confrontation, all you'd have would be the kids, scattered all over the country, and the guardsmen, dressed in civilian clothes and spending the week at their regular jobs. So it's not what they are that's important -- it's what they're doing there.

Wexler does the third thing, too. He evokes our memories of the hundreds of other movies we've seen to imply things about his story that he never explains on the screen.

The basic story of the romance (young professional falls in love with war-widow, gradually wins friendship of her hostile son) is certainly not original. If Wexler had spelled it out, it would have been conventional and boring.

Instead, he limits himself to the characteristic and significant aspects of this relationship (the boy likes pigeons, the woman is a teacher, the location is Uptown, the time is the Democratic convention, the woman seems more genuine to the cameraman than the model he's living with). And these are the scenes Wexler shoots. The rest of the romance is implied but never shown; we skip B on our way from A to C.

"Medium Cool" is finally so important, and absorbing because of the way Wexler weaves all these elements together. He has made an almost perfect example of the new movie. Because we are so aware this is a movie, It seems more relevant and real than the smooth fictional surface of, say, "Midnight Cowboy."

This is even true of the last scene -- that accident that happens for no reason at all. Accidents are always accidents, and they always happen for no reason at all. When we get it, it occurs to us that it's the first movie accident we've ever seen that we weren't expecting for at least five minutes.