There is a part of me that would sit at home all day reading true crime books and doing nothing else. I'm particularly attracted to stories set in the present, among ordinary people who would not think of themselves as criminals, but who one day commit a violent crime and think they can get away with it. The papers are filled with these stories, about jealous spouses and secret lovers, ancient grudges and fatal miscalculations, teenage boyfriends and elderly recluses, usually with sex on their minds. When they are caught, as they almost always are, the perpetrators of these crimes turn into accomplished courtroom performers who begin to enjoy their overnight fame, to think of themselves as stars instead of defendants.

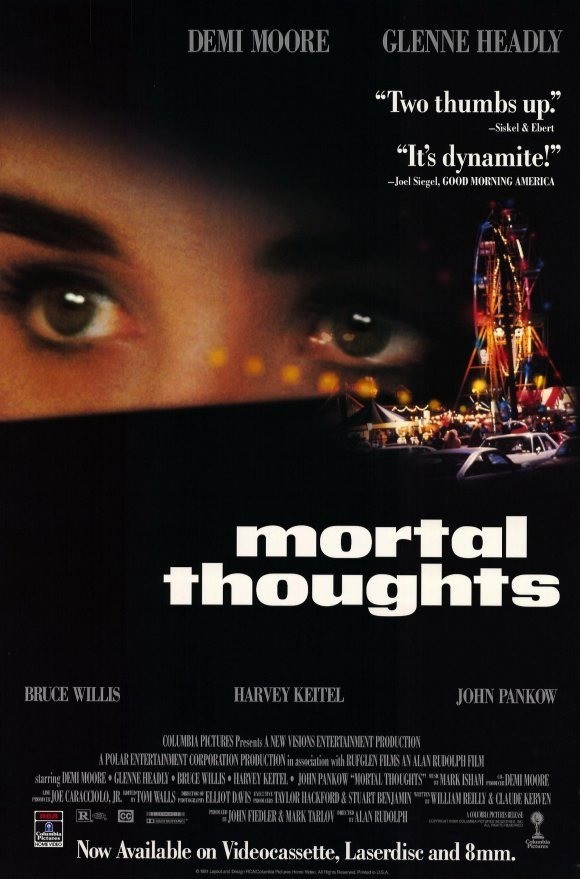

Alan Rudolph's "Mortal Thoughts" is a movie just like the true crime stories I enjoy the most. It's about two friends who work in the perfectly named Clip ‘n' Dye beauty parlor in Bayonne, N.J.

The owner Joyce Urbanski (Glenne Headly) is married to Jim (Bruce Willis), an abusive lout of a husband who beats her, lies to her and grabs money out of the cash register to go buy booze and drugs.

Joyce's friend and business partner, Cynthia (Demi Moore), is a fascinated witness to the increasing violence in the Urbanski marriage. Her own marriage, to the boring but dedicated Arthur (John Pankow), seems to be just the opposite.

The two women engage in deadly but entertaining brinksmanship over the question of whether Jim, who everybody agrees is a reprehensible brute, should be murdered. Joyce is frequently overheard saying she'd like to knock her husband off, and on one occasion she even fills the sugar bowl with rat poison and tells Cynthia all about it - and Cynthia has to run upstairs to save Jim's life. She is thanked for her troubles by Jim's clumsy sexual advances and adolescent pawing.

Then one night Jim and the two women go to a carnival, and Jim dies, or is murdered, and the women conspire to hide the body and cover up the death. We learn all of this a few days later, during a police interrogation being carried out by two detectives (Harvey Keitel and Billie Neal). They have Cynthia in a small room and are videotaping her as they lead her through the details of the crime.

There are a lot of unanswered questions, such as exactly how the husband was found dead, who found him, what happened then, and why. There is even another death to consider, although to discuss it would spoil a surprise for you, and indeed this whole movie is an unfolding series of surprises and revelations. It begins as a case history, turns into a whodunit and ends by trying to determine what was done, among other questions.

Like many crimes, the ones in this movie seem simple at first and only grow complicated the more you look at them. The screenplay, by William Reilly and Claude Kerven, is meticulously constructed so that the flashbacks during the testimony never reveal too much, and yet never seem to conceal anything. Nor is the screenplay simply ingenious; it is also very funny, in a mordant and blood-soaked way, as these two women scheme and figure and lie to the cops, to each other and to themselves. There is a banality to their language and images that sets the correct tone.

The way Cynthia and Joyce squirm to justify and defend themselves is deliciously fraudulent. It's in my nature to be fascinated by criminals, perhaps because I lack the stuff to be one myself. I am so intimidated by the police that I recently succeeded in getting myself ticketed for non-compliance with the city auto emission ordinance even though I had a current emission control sticker on my windshield. Manifestly innocent, I was somehow convinced of my own guilt, and did not protest even while the trooper wrote an unfounded ticket.

Yet there is another level to "Mortal Thoughts" than either the guilt or innocence of the characters, or the wit with which Rudolph portrays their world. It is the level on which ordinary people cut themselves loose from ordinary morality, who commit crimes for their own convenience. Human life should be sacred, but we live in a world where people are killed simply to make life easier for their murderers. Maybe that's why the killers' alibis are often so pathetic and their planning is so slipshod: If the murderers really took murder seriously, they'd take the time and trouble to get away with it.