Charlie can't feel big emotions—especially joy—otherwise it will make him pass out. It's part of a disease he has called cataplexy, in which any large emotion confuses his brain chemistry and causes him to shut down, making him faint right where he's standing. He's had it all his life, and it makes him resistant to experience a deep feeling of love. But one can imagine he'd be safe watching "Ode to Joy," a plainly affable romantic comedy that's not too powerful with its romance, and certainly not its comedy.

Played by Martin Freeman, Charlie's a likable guy who is privy to some unfortunate slapstick. Take the opening wedding scene, where Charlie looks like he's miserable just standing in front of his sister who is about to be married. It makes for good comedic tension, especially as his sister tells the priest to speed up the nuptials, and his brother Cooper (Jake Lacy) tries to keep him propped up, knowing what's coming next. The tension gets a big, darkly comic payoff—right at the ceremony's big moment, Charlie goes completely numb, and crashes down like a building onto a whole display of flowers, in front of everyone to see.

Written by Max Werner and based on a story from "This American Life" by Chris Higgins, "Ode to Joy" imagines what this disease would do to a person, how it would make them feel day-to-day, and about their lives. Freeman gives an appropriately neurotic, weary performance, a type of man whose safe zone is in being a grump, and is exhausted by it. Freeman sells the concept as more than just "an adorable quirk," as Cooper calls it, even if sometimes the script is a bit vague about just how susceptible he can be. But it's funny to watch him walk around New York City, with "Siegfried's Funeral March" playing in his earbuds, muttering things to himself like "Darfur, white men in dreadlocks" while trying to keep his eyes averted from normally pleasing, little instances of happiness around him.

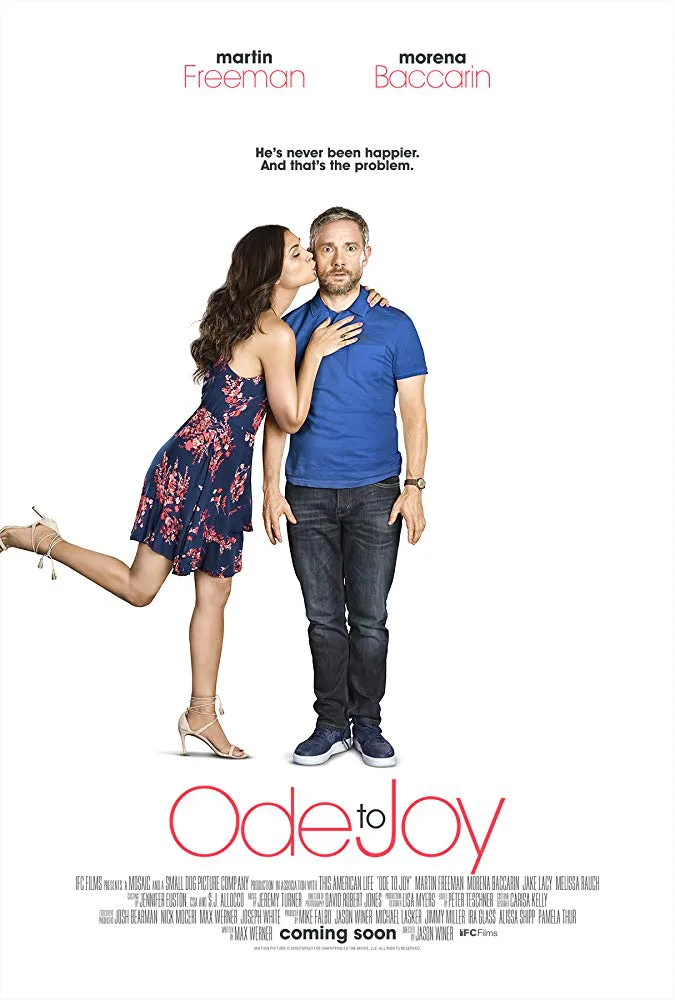

And then as romantic comedy premises go, there's also some good promise of tension. Who would be a good match be for someone with cataplexy? The answer is Francesca, played with zeal by Morena Baccarin, the anti-Charlie: she's not afraid to be bold with her feelings, and pursue what she wants. Her big flaw is that she likes men for what they aren't (something that's addressed twice by the script for emphasis), a trait meant to show how awkward librarian Charlie could be a bit irresistible to her. That's about as much as the story gives to why she'd soon fall for him soon after seeing his curmudgeonly ways, while he tries to push her away despite his own attraction. This causes her to seek advice from her dying Aunt Sylvia (Jane Curtin), a side relationship that the story uses to give Francesca a bit more dimension than just a force that comes into Charlie's life.

"Ode to Joy" then puts these two into a tedious scenario, with Charlie manipulating the dopey Cooper to try to date Francesca so that Charlie can still be around her, but not worry about getting too emotionally attached. It's a doomed match, but only Charlie knows that. Meanwhile, Charlie starts to see Bethany (Melissa Rauch), a woman he perceives as too dry to get him worked up in any fashion, inflicting jealousy on Francesca's side. As Charlie makes it worse for everyone by denying his feelings for Francesca, afraid of being too much for her or embarrassing himself, "Ode to Joy" is mostly about watching these characters get over themselves. But it's all too obvious, even for the mechanics of the genre, and there's not a lot of fun to whatever playfulness Werner's script has.

Charlie may not be able to handle the joy of comedy, but director Jason Winer's film offers little when it comes big laughs. It takes tried-and-true talents like Jake Lacy and Melissa Rauch and gives them weak comedy bits that are kooky at best—here's Lacy's bad impression of Robert De Niro, or here's Rauch belting out a famous ‘90s song while playing cello. Add in the chops-busting peanut galleries that Charlie and Cooper both have in their respective workplaces, and the movie loses its charms by taking an inspired character and dumping him into a tale that feels anything but.