"I have spent more than half of my adult life in prison," says Darius McCollum. Films have taught us what to think of people who say that. But unless you already know his name—and if you live in New York there's a good chance you do—then whatever assumptions you are making about McCollum are probably wrong.

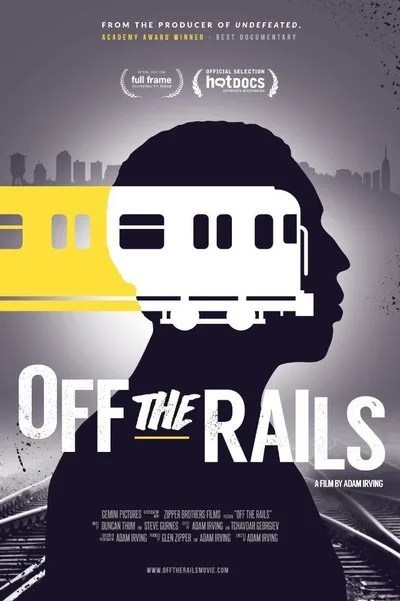

The charismatic man at the center of Adam Irving's new documentary has been jailed 32 times for working for New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The problem is that they don't employ him. He repeatedly steals buses and subway trains, and drives them safely to where they need to go.

McCollum has Asperger's syndrome and, like many people on the autism spectrum, he has an obsessive passion that consumes much of his life. For some it's drawing, for others it's a TV show. For McCollum it's trains. "Ever since I was 15 years old I've been running towards the subway system," he says.

Actually, it's longer than that. He's been running to the subway since he was a small boy. It was just at age 15 that he was first arrested. At school, happy and broad-smiling but also nerdy and awkward, he was badly bullied and, one day, while he sat arranging a jigsaw puzzle, another pupil stabbed him, almost fatally, with scissors. After he left hospital little Darius became afraid of school and began to ride the subway all day.

His astounding encyclopedic knowledge of trains, and his eagerness to help out, endeared him to MTA employees, who thought of him as a kind of mascot. After a couple of years they gave him his own miniature MTA uniform. When he was 12, he was allowed to operate a train under supervision, and when he was 15 a train driver who wanted to skip work to visit a girlfriend told Darius to take over for him.

Darius drove a train safely through eight stops, picking up passengers and letting them off, and made all the necessary announcements. But someone spotted that he did not look old enough to be driving a train and so he was arrested. The incident made headlines.

Aged 17, and then again aged 18, McCollum applied to work for the MTA but having the notorious teenage train bandit on staff seemed like bad PR, and he was rejected. His obsession with New York's public transport system did not diminish.

"Off The Rails" uses interviews, animation and dramatic reconstructions to tell McCollum's strange story but these devices are never flashy or distracting. With justice to fight for this could be an angry documentary but instead it's a gentle one. In the foreground there is always McCollum's daily life and in the background there is always the implication that a better society, one with more informed attitudes to autism and mental health, would be better able to deal with him.

The film's message is quiet but clear: Darius McCollum is black and neurodivergent, and society treats him differently than it would if he were white and neurotypical. The justice system, in particular, seems designed to chew him up.

At one point, while McCollum is in prison for illegally driving a bus, his parents retire to North Carolina. They hope that when he is released their son will join them. There he will be with those who love him and, away from the New York Subway System, he will not be able to steal its trains. But when he is released the conditions of his parole forbid him to leave New York and he is soon arrested for riding the subway when he has been banned from entering it. He goes back to jail for another year.

Stealing mass transit vehicles is a major offence and so, when McCollum is incarcerated, he is sent to maximum security prisons, some of which—Attica, Sing Sing, Rikers Island—are infamous in popular culture. McCollum's crimes have never harmed anyone or even caused any real disruption to the MTA and yet he is imprisoned alongside gang leaders and rapists and murderers. In Rikers Island he survived a riot and was scalded when another inmate boiled baby oil and poured it over him as he slept in his cell.

As a prisoner, McCollum consulted with the MTA. He advised on security and safety, and improvements were made on his recommendations. But when he was released the MTA would still not employ him.

Even worse, while he was inside, prison authorities became concerned that his extensive knowledge of the public transport system could make him a target for incarcerated terrorists seeking to manipulate him, so he was put into segregation. Rules dictate that segregated prisoners be shackled, and so he was.

Legally, the alternative to this kind of incarceration is to argue that McCollum is insane but, if he is, then the law says he is criminally insane, and that means he would be locked away indefinitely with dangerously disturbed prisoners. To be released, he would need to be cured of his apparently incurable compulsions. And so the cycle continues. There should be a solution but the tangle of social workers and psychiatrists and judges and lawyers and the MTA seems unable to produce one.

Adam Irving is on McCollum's side—he would hardly have made this documentary if he wasn't—but "Off The Rails" makes few appeals on McCollum's behalf and commits to illustrating that, regardless of how much he is abused by the system, he is narcissistic and boastful and keen on attention. But even so the evidence that we need to treat neurodivergent people better than we do keeps building.

As I wrote this review a friend asked what I was working on and I told her McCollum's story. "Why can't someone show some common sense or compassion?" she asked. This is a good question. "Off The Rails" asks it well. Society ought to answer.