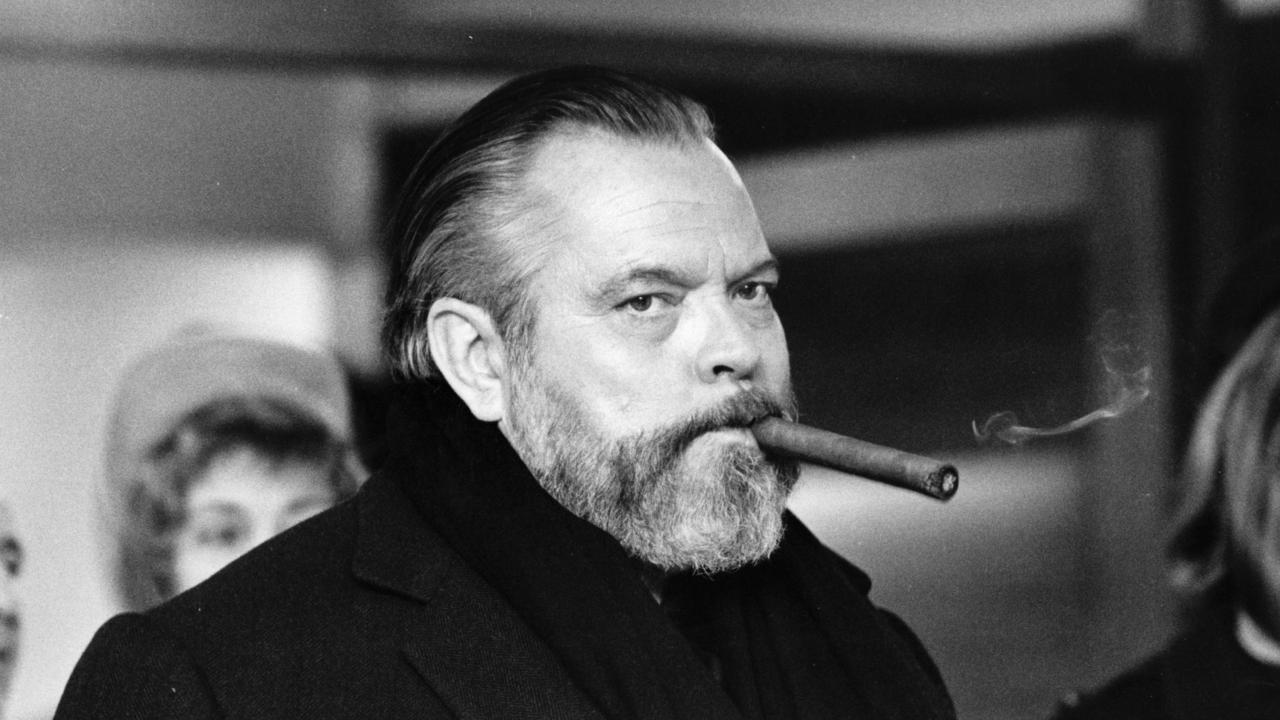

"It's a film which humbles us a bit because it's by a man who thinks more swiftly than we do, and much better, and who throws another marvelous film at us when we're still reeling under the last one. Where does this quickness come from, this madness, this speed, this intoxication?"

— Francois Truffaut on Orson Welles

The great French critic and filmmaker Francois Truffaut was also a juvenile delinquent of the first rank. Whether among the graft and petty crimes he carried out was pinching the lobby cards of "Citizen Kane" from a Paris theater, as his alter ego, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Leaud), performs with admirable stealth and invention in Truffaut's autobiographically inflected first feature, "The 400 Blows," the sense of indebtedness of one significant artist to another has rarely been so beautifully acknowledged.

In a 1967 essay, Truffaut wrote about the director and his revolutionary debut: "Because Welles was young and romantic, his genius seemed closer to us than the talents of the traditional American directors. We loved this film because it was so complete—psychological, social, poetic, dramatic, comic, grotesque. 'Kane' both demonstrates and mocks the will to power; it is a hymn to youth and a meditation on age, a study of the vanity of all human ambition and a poem about deterioration, and underneath it all a reflection on the solitude of exceptional beings, geniuses or monsters, monstrous geniuses."

George Orson Welles came to this world 100 hundred years ago, born on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin. (Welles's Wisconsin years are the subject of "Young Orson," a new work by Patrick McGilligan, historian and cultural critic who has published biographies of Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang and Nicholas Ray.)

Many other cities have claimed him, including Chicago, where he came to live after his parents' marriage broke up and his earliest artistic activities were cultivated at the progressive and by all accounts remarkable Todd School, in Woodstock, Illinois. His beloved mother Beatrice died when he was nine, his father Dick, an entrepreneur and inventor, when he was 15. His first patron and benefactor was the Chicago doctor and opera enthusiast, Dr. Maurice Bernstein.

Rarely a time passes where you should not think about Orson Welles and his towering achievements on the form, shape and being of the movies. On the occasion of his centenary (and the 30th anniversary of his death), Orson Welles is, where he belongs, pretty much everywhere. Major conferences and film retrospectives have either been staged or are forthcoming at Indiana University, University of Wisconsin in Madison, University of Chicago and Woodstock, just for starters.

Turner Classics Movies is dedicating every Friday evening this month to the director's idiosyncratic, exuberant and melancholy output. The Cannes Classics program is unveiling, with the start of next week's festival, two documentary on Welles and special 4K restorations of "Citizen Kane," "The Lady from Shanghai," and his best known performance in somebody else's film, his marvelously decadent black marketeer in Carol Reed's "The Third Man."

The boutique New York label Janus Films and Criterion have announced a joint venture to reissue, for both theatrical and a subsequent Blu-ray, the director's 1966 "Chimes at Midnight," his magisterial Shakespeare adaptation. The movie (also known as "Falstaff") has never been "lost," but it has never been shown in ideal circumstances. (A British Blu-ray has also just been released.)

The writer Josh Karp has published "Orson Welles's Last Movie," about the intractable and complex legal, personal, political and financial reasons that have prevented Welles's last major work, "The Other Side of the Wind," from completion and exhibition. A group of producers are currently at work with the meticulous and complex finishing process, though are dealing with their own financial struggles in raising the necessary completion funds, having announced a $2 million Indiegogo campaign today.

In addition to the books by McGilligan and Karp, F.X. Feeney has published a new cultural and critical evaluation, "Orson Welles: Power, Heart and Soul." The filmmaker, actor and playwright Simon Callow is also completing the third volume of his Welles biography.

The situation on video and streaming is far from ideal, though it has improved of late. "The Lady from Shanghai" is out, for the first time, in a high-definition edition by the specialist label, Mill Creek. Universal has published a limited edition Blu-ray of "Touch of Evil," offering all three versions of the film—most importantly the 1998 re-edit supervised by editor Walter Murch based on Welles's 59-page memo to Universal executives after the film was taken out of his control. (It also features a great audio commentary by Welles's experts Jonathan Rosenbaum and James Naremore.)

Criterion recently put out a high-definition version of "F for Fake," the penultimate of Welles's completed works (his beautiful late essay film, "Filming 'Othello,'" is unfortunately virtually impossible to track down). It features some great supplements as well, such as a commentary track by Welles's longtime companion and key collaborator, Oja Kodar and the cinematographer for his late projects, Gary Grover, a video introduction by Peter Bogdanovich and an essay by Rosenbaum.

The label also has a beautiful and deluxe boxed set, "The Complete Mr. Arkadin," which features three of what Rosenbaum has cited as seven circulating versions of that film. The only drawback there is it is in standard definition. The wealth of assembled materials is astounding, featuring another Rosenbaum and Naremore commentary track, a documentary featuring Bogdanovich and an interview with Callow.

Criterion's streaming channel on Hulu Plus features "F for Fake," "The Complete Mr. Arkadin," and one of the director's striking curiosities of his European exile, "The Immortal Story." It is adapted from a short story by one of the director's favorite writers, Isak Dinesen from her collection, "Anecdotes of Destiny," featuring Welles and Jeanne Moreau, an hour-long work originally commissioned for French television.

Available to stream on its own channel on Hulu Plus, Kino Classics published a remastered high-definition edition of Welles's 1945 "The Stranger," his most commercially successful work. On Netflix, the only streaming title of a film directed by Welles available is his 1962 Kafka adaptation of "The Trial."

Fittingly, in the most tragic example of a film taken out of his control and mutilated, his 1942 second feature, "The Magnificent Ambersons," from the Booth Tarkington novel, had nearly 50 minutes of material removed from Welles's version and inexplicably destroyed. Criterion published a dazzling laser disc edition featuring Welles's radio adaptation material and copious extras to fill in the deleted material. Rights problems have prevented Criterion from producing the same material on Blu-ray. The only US version is a standard definition copy that was originally introduced as an Amazon exclusive to a 70th anniversary Blu-ray of "Citizen Kane." The version is now sold separately but is out of print.