Alcoholics or drug addicts feel wrong when they don't feel right. Eventually they feel very wrong, and must feel right, and at that point their lives spiral down into some sort of final chapter--recovery if they're lucky, hopelessness and death if they're not.

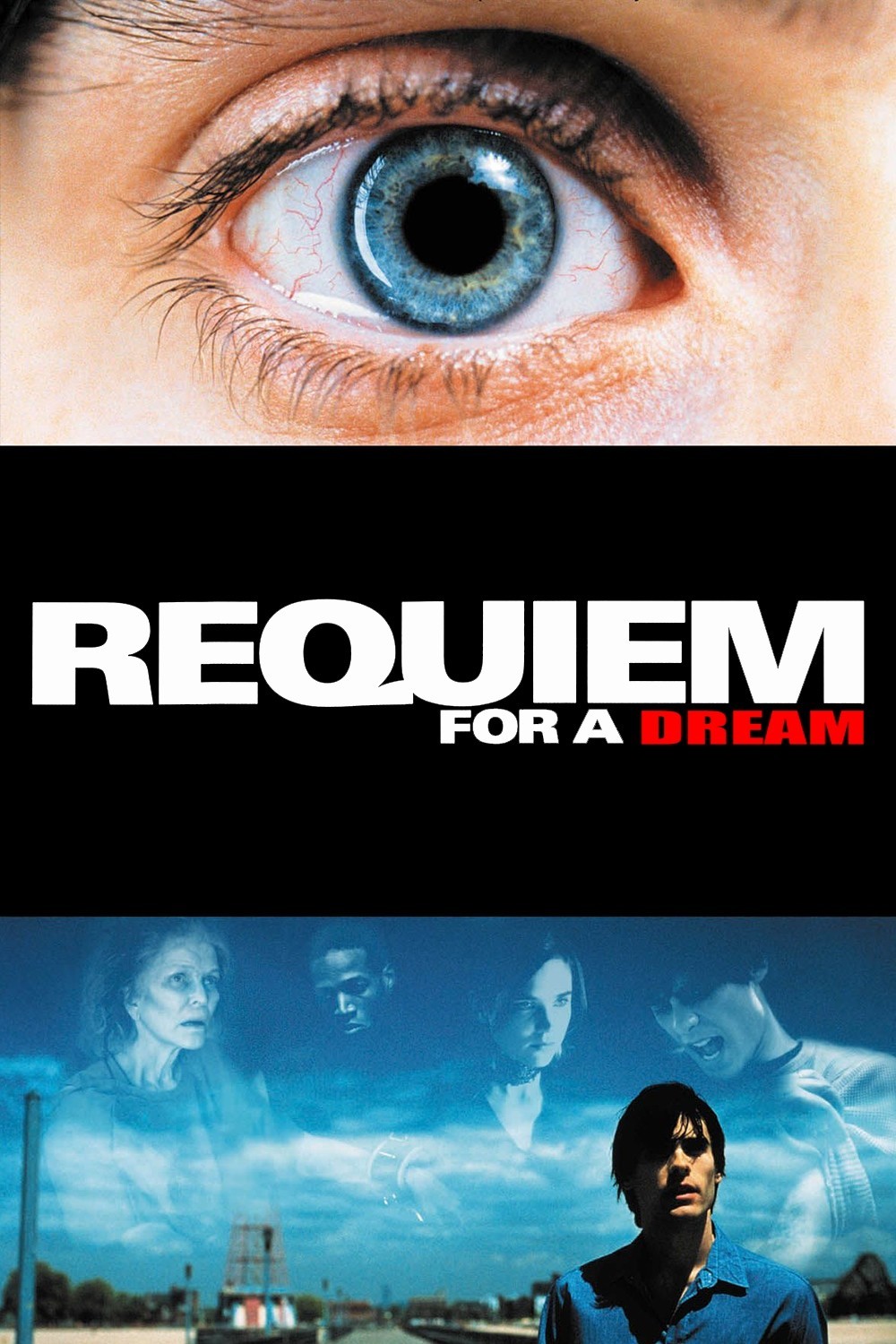

What is fascinating about "Requiem for a Dream," the new film by Darren Aronofsky, is how well he portrays the mental states of his addicts. When they use, a window opens briefly into a world where everything is right. Then it slides shut, and life reduces itself to a search for the money and drugs to open it again. Nothing else is remotely as interesting.

Aronofsky is the director who made the hallucinatory "Pi" (1998), about a paranoid genius who seems on the brink of discovering the key to--well, God, or the stock market, or whatever else his tormentors imagine. That movie, made on a tiny budget, was astonishing in the way it suggested its hero's shifting prism of reality. Now, with greater resources, Aronofsky brings a new urgency to the drug movie by trying to reproduce, through his subjective camera, how his characters feel, or want to feel, or fear to feel.

As the movie opens, a housewife is chaining her television to the radiator. It's no use. Her son frees it, and wheels it down the street to a pawn shop. This is a regular routine, we gather; anything in his mother's house is a potential source of funds for drug money. The son's girlfriend and best friend are both addicted, too. So is the mother: to television and sugar. We recognize the actors, but barely. Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn) is fat and blowzy in her sloppy house dresses; if you've just seen her in the revived "Exorcist," her appearance will come as a shock. Her son Harry (Jared Leto) is gaunt and haunted; so is his girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly). His pal Tyrone is played by Marlon Wayans, who has lost all the energy and cockiness of his comic persona and is simply trying to survive in a reasonable manner. Tyrone suspects, correctly, that he's in trouble but Harry is in more.

Sara's life passes in modest retirement. She joins the other old ladies out front of their building, where they line up their lawn chairs in the sun. She's addicted to a game show whose host (Christopher McDonald) leads the audience in chanting "We got a winner!" She's a sweet, naive women who gets a junk phone call that misleads her into thinking she may be a potential guest on the show. She obsesses about wearing her favorite red dress, and gets diet pills from the doctor to help her lose weight.

She does lose weight, and also her mind. "The pills don't work so good anymore," she complains to the druggist, and then starts doubling up her usage. Her doctor isn't even paying attention when she complains dubiously about hallucinations (the refrigerator has started to threaten her). Meanwhile, Harry talks to Marion about the one big score that would "get us back on track." Tyrone can see that Harry is losing it, but Marion, under Harry's spell, has sex with a shrink (Sean Gullette, star of "Pi") and is eventually selling herself for stag party gang-gropes.

Aronofsky is fascinated by the way in which the camera can be used to suggest how his characters see things. I've just finished a shot-by-shot analysis of Hitchcock's "The Birds" at the Virginia Film Festival; he does the same thing, showing us some things and denying us others so that we are first plunged into a subjective state and then yanked back to objectivity with a splash of cold reality.

Here Aronofsky uses extreme closeups to show drugs acting on his characters. First we see the pills, or the fix, filling the screen, because that's all the characters can think about. Then the injection, swallowing or sniffing--because that blots out the world. Then the pupils of their eyes dilate. All done with acute exaggeration of sounds.

These sequences are done in fast-motion, to show how quickly the drugs take effect--and how disappointingly soon they fade. The in-between times edge toward desperation. Aronofsky cuts between the mother, a prisoner of her apartment and diet pills, and the other three. Early in the film, in a technique I haven't seen before, he uses a split screen in which the space on both sides is available to the other (Sara and Harry each have half the screen, but their movements enter into each other's halves). This is an effective way of showing them alone together. Later, in a virtuoso closing sequence, he cuts between all four major characters as they careen toward their final destinations.

Burstyn isn't afraid to play Sara Goldfarb flat-out as a collapsing ruin (Aronofsky has mercy on her by giving her some fantasy scenes where she appears on TV and we see that she is actually still a great-looking woman). Connolly, who is so much a sex symbol that she, too, could have disgraced herself in "Charlie's Angels," has consistently gone for risky projects and this may be her riskiest; the movie is inspired by Hubert Selby, Jr.'s lacerating novel of the same name, and in her own way Connolly goes as faras Jennifer Jason Leigh did in "Last Exit to Brooklyn" (1989), an equally courageous, quite different, film based on another Selby novel. Leto and Wayans have a road trip together, heading for Florida, that is like a bleaker echo of Joe Buck and Ratso Rizzo's Florida odyssey in "Midnight Cowboy." Leto's suppurating arm, punished by too many needles, is like a motif for his life.

The movie was given the worthless NC-17 rating by the MPAA; rejecting it, Artisan Entertainment is asking theaters to enforce an adults-only policy. I can think of an exception: Anyone under 17 who is thinking of experimenting with drugs might want to see this movie, which plays like a travelogue of hell.