In his landmark 1968 study of the American director Howard Hawks, the critic Robin Wood identified a key theme in Hawks' work: "the lure of irresponsibility." As a filmmaker Clint Eastwood is possibly more a William Wellman man than a Hawks one, but some of his pictures, most explicitly 1993's "A Perfect World," partake of a Hawksian dynamic. His new movie "Richard Jewell," about the man who did heroic service at a terrorist bombing in Atlanta during the 1996 Olympics, only to face accusations of staging the bombing itself, is about a number of things, and the lure of irresponsibility is among them.

It's not a lure to which the title character is immune. An early scene in this fleet, densely textured drama shows Jewell, played by Paul Walter Hauser with an empathy that seems genuinely lived-in, working as a college security guard. Derisively referred to as a "rent-a-cop" by students, he in turn inappropriately lords it over them. A meeting with a dean ends with the academic saying "Do you want to resign, or would it be better if I fired you?"

Years later, hired as a freelance security guard by AT&T, an Olympic Sponsor, to monitor music events at Centennial Park, Jewell is similarly heavy-handed, which actually proves useful when an actual pipe bomb explodes at an event. His work at securing a perimeter, as the pros call it, actually saves lives, and the less-than-socially adept Jewell is soon talking to Katie Couric on "The Today Show."

The adulation won't last. Jon Hamm's Tom Shaw, an FBI agent who had been at the site when the bomb went off, is assigned to look into Jewell. It's standard procedure. On-site "heroes" who actually precipitate the event at which they act heroically are sadly not uncommon. But Shaw's sense of having dropped the ball seems to inspire a rash zealousness. Shaw's feelings of wanting to have sex with an attractive woman lead him to give Jewell's name to Kathy Scruggs, a reporter for the Atlanta Journal Constitution who has aggressive methods of cultivating sources. On learning that Jewell's a target, Scruggs, played with nearly-disturbing aggressive exuberance by Olivia Wilde, exclaims "That fat fuck lives with his mother, of course."

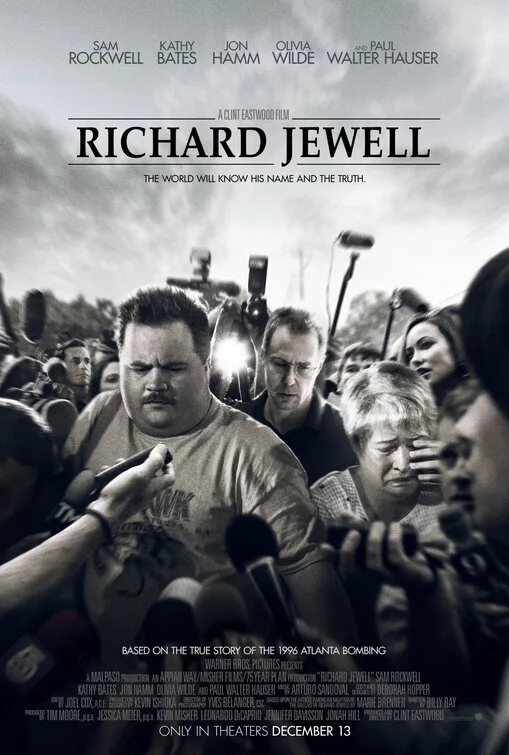

And Jewell, who does indeed live with his mother—played by Kathy Bates, who eventually steals the movie—now sees his life implode. A man with a near-irrational respect for law enforcement, he either looks on dumbly or says the wrong thing as FBI automatons remove his mother's underwear from their apartment and trembles with mute hurt as Tom Brokaw, who days before had praised him, smugly pronounces that the FBI is close to having enough to "nail" the innocent man. Soon, with the help of G. Watson Bryant, a relatively down-at-his-heels lawyer that Jewell knew when he was a supply clerk—played with such seamlessness by Sam Rockwell that you almost don't notice just how good he is, which is very—Jewell begins to fight back.

Eastwood's conceptions of heroism and villainy have always been, if not endlessly complex, at least never simplistic. One thing he's not is a moral relativist; he clearly believes in good and evil, and in good actors and bad actors. And so he, working from a script by Billy Ray (who treated journalistic malfeasance in his fact-based 2003 picture "Shattered Glass"), is unapologetic in making the bad actors here, Jon Hamm's FBI agent and Olivia Wilde's aggressive and callous reporter, pretty much bad to the bone. They both have their reasons, of course. Hamm's character is seething with resentment that the bombing happened on his watch, so to speak, and has made Jewell the target of that rage. Wilde's Scruggs is a scoop machine who keeps acting on the notion that she's got something to prove, which, as a woman in a largely male newsroom she probably, unfairly, did.

But having reasons doesn't make you right, and these two characters are very wrong. Eastwood's unabashed and unmediated depiction of Wilde's character in particular can't be anything but a deliberate provocation. Do you feel that the Scruggs portrayed here is a sexist stereotype, a tired trope? Eastwood's answer reminds one of a 2016 Trump campaign t-shirt (unofficial, I think): "Fuck Your Feelings."

The ace that Eastwood has in the hole is that whatever you think, what happened to Richard Jewell happened. The feeding frenzy around his story almost killed him, and Eastwood depicts this in a manner that's indignant while never running off the rails. It is true that the Atlanta Journal Constitution prevailed in Jewell's lawsuit against them (several other outlets settled), but they won on the grounds that the facts as the paper reported them at the time were accurate. The First Amendment is the First Amendment, yes—the irresponsibility is in the tone with which the story was pushed, the contempt with which Jewell was both portrayed and treated. And as much as Eastwood finds to condemn in the movie's designated villains, he does not deliver any comeuppances to them in the end. Which is merciful in the context of fiction, and kind of the mordant point in the context of fact.