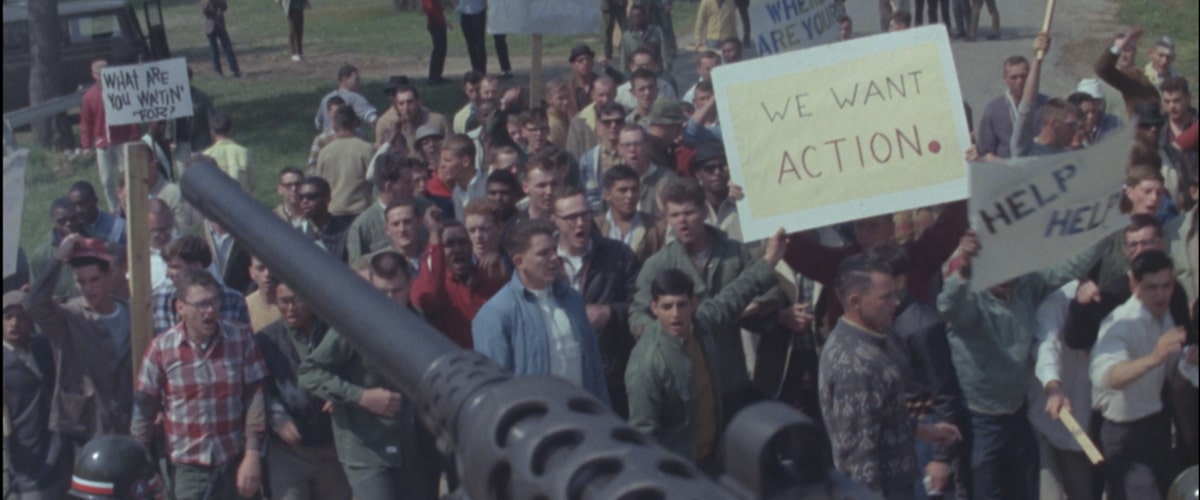

"Riotsville, U.S.A.," the title of director Sierra Pettengill bleak and intense documentary, sounds like a provocation on the filmmaker's part. Then you realize it refers to the actual name of a fictional place the U.S. military created in the 1960's. On two bases, both named for racists, a series of staged activities were performed against a fake backdrop created to look like the inner city. These exercises were supposed to mimic rioting and the recommended police and military response. Soldiers played the parts of law enforcement and "troublemakers." Not only did the performers have a live audience, the drills were also recorded for posterity.

Using only archival footage, Pettengill and her editor, Nels Bangerter fashion a searing indictment of the militarization of the police force as a response to civil unrest. The material comes from the military's recordings, shows on a precursor to PBS, footage of community hearings and news reports of the 1968 Republican Convention. Most of the time, it is presented as it was recorded, but on occasion, the director intentionally blurs or obscures footage as if inspecting it under a microscope. The result draws even more attention to Charlene Modeste's haunting reading of writer Tobi Haslett's masterful narration.

"A door swung open in the late '60s," Modeste tells us. "And someone, something, sprang up and slammed it shut." In 1967, President Johnson created The Kerner Commission, named after the governor of Illinois, Otto Kerner. The commission was made up of "political moderates" whose job was to discover the reasons for civil unrest. By that time, the U.S. had been privy to numerous rebellions; that year saw major uprisings in Newark and Detroit, and two years prior, the Watts Rebellion happened in Los Angeles. These were Black areas where the lack of sufficient housing and employment, and the surplus of police violence, predicated the responses of people fed up with these situations.

In his 1968 speech, "The Other America," Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said "a riot is the language of the unheard." The unheard were finally raising their voices, and the government felt pressured to listen. However, LBJ had an ulterior motive in that he hoped his commission would conclude that "outside agitators" were the reasons for cities burning. As if the denizens were too stupid to see the injustices all around them, and therefore needed a more intelligent and sinister agent to stir the pot.

Instead, the Commission's report was a 700-page published bestseller that concluded "our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one White. Separate but unequal." Their solution to rectify that would cost $2 billion a week, about the same amount LBJ was spending on Vietnam. H. Rap Brown, who was in prison on an inciting to riot charge, responded that "the Kerner Commission people should be in jail with me, because they're saying what I've been saying."

Of course, this was not the desired answer. However, the Kerner Commission did provide an out of sorts, and it's the one thing the government decided to latch onto as a means of action: Increase the budgets of law enforcement in major cities. This leads to police officers driving military tanks and even a boxy, armored car that shot enormous amounts of tear gas. There's also footage of little old White ladies going to target practice to protect themselves from that evil Negro menace should it come to their pristine little towns. "I don't like the idea of shooting anybody," says one bespectacled woman, "but if I have to…"

Meanwhile, "Riotsville, U.S.A." splits its narrative between scenes of the titular location and footage from a progressive precursor to the Public Broadcasting System that was ultimately defunded by the Ford Foundation for being too incendiary. The latter features community meetings between Black people and White cops. It's no surprise that the cops swear up and down that there's no racism amongst their forces. It's even less of a surprise when the Black folks angrily counter that with proof. "We're getting our asses kicked out here by the police," yells the preacher of the church that participated in one such round table.

Over at Riotsville, a group of all-White spectators watch the soldiers play cops and robbers, with Black participants screaming "I'll be back to get you" as they're arrested. The audience cheers as these play-acting rabblerousers get violently flung into cop cars and wagons. There's even a re-enactment of the Watts Rebellion, for entertainment purposes only. The footage is jarring and garish, but the filmmakers can't be accused of shooting it to look this way. This is the way it was shot by the U.S. military. There's also constant mention of snipers running rampant during riots, a falsehood disproven by Kerner's commission that kept getting repeated anyway as a form of gaslighting people into believing it.

It all leads up to footage of the 1968 Republican National Convention. The Democratic Convention got all of the press that year, but "Riotsville, U.S.A." shows that the GOP's Miami-based convention was a real-life test run of the concepts crafted in Riotsville simulations. The Black denizens of Liberty City, many of whom protested the GOP's nearby presence, were the recipients of this gruesome show of force. This footage is supplemented by coverage of NBC reporters covering the convention telling boldfaced lies about the protests before pivoting to introduce ads from Gulf, one of the manufacturers of the tear gas being used outside.

"Riotsville, U.S.A." is certainly not an objective documentary. It's angry and it dares the viewer to argue back. The freeform nature of it may seem faulty, but I felt it served the purpose of forcing me to interrogate what I was being shown. The smartest thing Pettengill does is to stay rooted in this past footage while not making a single comparison to events of today. She doesn't have to; when a Black woman says, "if we were being told to arm ourselves the way those White women are being told, the response would be different," her comment makes any contemporary references redundant. Then, as in now, rebellions were judged by what color the participants are.