Midway through the one-take indie thriller "Soft & Quiet," a pregnant white woman with bleached blonde hair and a leopard print cardigan says that she was born into the KKK, but these days she's more active on the Neo-Nazi website Stormfront. "The media loves to portray us as big scary monsters. Am I really that scary?" she says, a wide smile plastered onto her face. No, and that's the point.

In a press statement, writer/director Beth de Araújo says that "Soft & Quiet" was inspired by the viral video from May 2020 of a white woman, Amy Cooper, harassing Black bird watcher Christian Cooper in Central Park. And while the actions of the nice white ladies in her film are more extreme, they're just as commonplace. White supremacy is not just men in hoods burning crosses; it shows up everywhere, from suburban elementary schools to locally owned mini-marts. And white women are the chief enforcers of this "Soft & Quiet" form of racism.

De Araújo's film underlines this point, following a seemingly ordinary kindergarten teacher named Emily (Stefanie Estes) through an afternoon in her life. She leaves the school where she works, clutching a homemade cherry pie wrapped in foil. She walks over to a nearby church, where she hugs and greets a gaggle of similarly put-together white ladies dressed in Old Navy separates. Amid this domesticated crew are two younger women, both of them in hoodies with piercings and dyed hair. Emily sets her pie down on the table and lifts the wrapper for a shocking reveal: She's carved a swastika into the upper crust. "Is this a joke?" one of the women asks. It's not, but they play it off as one.

Each of the members of Emily's nascent far-right women's group represents a different face of white supremacy: The radicalized punk, the bitter Boomer, the homeschooling housewife, the legacy racist. And the rationales they present for their bigoted views run a similar gamut, evoking "common sense," "pride in one's heritage," and "reverse racism." Black Lives Matter started it, they argue. They don't hate anyone. They're just defending their way of life. These catchphrases will be familiar to anyone who's been at all politically engaged over the past five years or so. And de Araújo systematically presents each of them, words that will later be destroyed by her characters' actions.

While impulsive ex-con Leslie (Olivia Luccardi) is the one who tips the afternoon's proceedings into the hate-crime territory, throughout the film Emily emerges as a truly terrifying, even evil, figure. She's knowingly bringing together disillusioned women and indoctrinating them into white supremacist talking points, molding them into useful soldiers in her imagined race war. She uses white supremacist ideas about gender and femininity as weapons as well, leveraging the sexism and homophobia of the movement to avoid responsibility for her actions. Her voice trembles when she asks her husband, "Do you want me to look at you like a f—, babe?" using an anti-gay slur to bully him into accompanying her on a dark errand midway through the film.

"Soft & Quiet" continues to escalate once that pie hits the table, from veiled references to "urban" kids to racial slurs to overt acts of intimidation and violence. Watching the excitement with which these women dig into ugliness once they realize that they're among "like-minded" people is disturbing: At one point, a woman gives a Nazi salute, and the rest of them break down in giggles. "You're so bad," they squeal, as if she just suggested they order a second dessert. But the most disturbing part is their casual, instinctual weaponization of white female victimhood. Tears, quivering voices, claims that an Asian-American woman was "threatening" them over a "practical joke"—none of these women will own their bigotry in public, because the system is set up so they don't have to.

But although "Soft & Quiet" is extremely effective as a piece of educational agitprop, it contains a few too many contrivances to really gel as a narrative. And the real-time, one-take gimmick limits its possibilities in terms of character. There's also the issue of a disconnect between the viewers who need to see this film the most—suburban white women who voted for Trump—and the typical audience for edgy indie thrillers like this one. But transcending the culture wars is a distribution challenge, not a creative one.

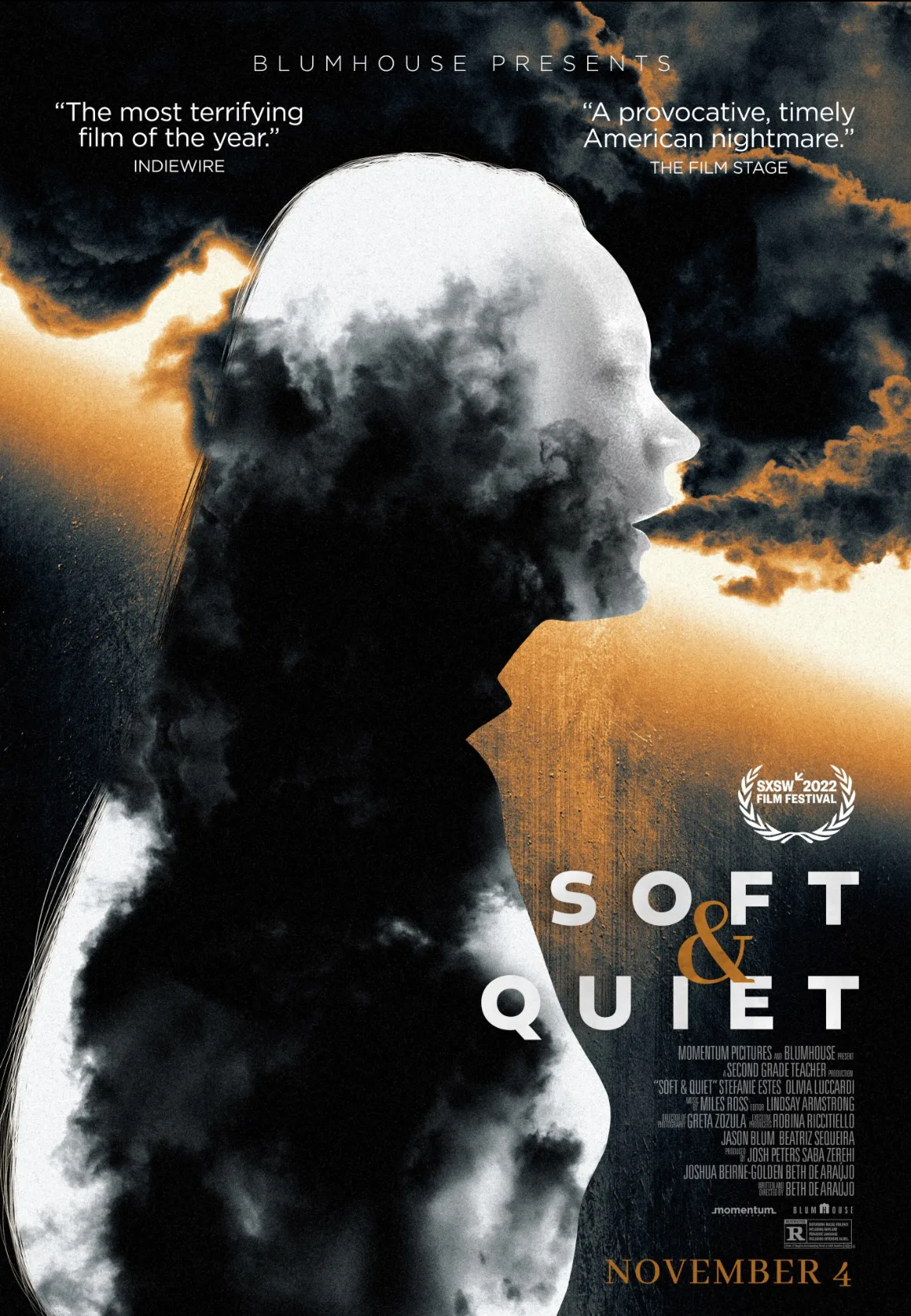

The handheld camerawork, with cinematographer Greta Zozula stalking the characters like a silent shadow, does create a palpable sense of confusion and panic when the film goes off the rails in its last half hour. Until then, its ordinariness conveys a different message—emphasizing the everyday nature of white supremacy, de Araújo's primary goal for the film. "Soft & Quiet" is being marketed as a horror movie, thanks to the harsh cruelty on display on the screen. In practice, however, it's something messier and more challenging than that.

"Soft & Quiet" leaves an upsetting aftertaste. This is a movie that few will want to watch twice, and if people of color decide to skip it for their own peace of mind, that's understandable. It's white people who need to hear and see these things, not those who already know them from personal experience. That being said, the film comes directly from its writer/director's own lived experiences with racism, which gives it a rawness and an urgency that's hard to ignore. And given America's cognitive dissonance about the looming threat of white supremacy in this country, an unsparing take on an issue like this one is very much needed. If you feel sick watching this movie, that means it's working.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.